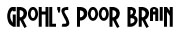

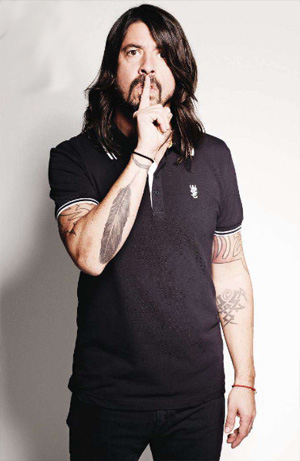

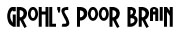

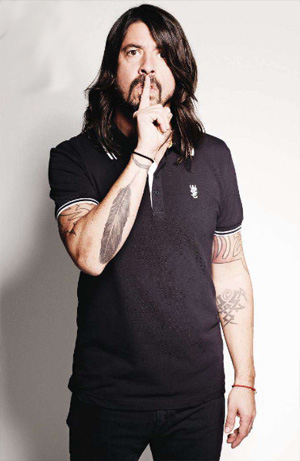

Rock Of Ages

Nylon Guys

On the release of his best record in a decade, Dave Grohl opens up about fatherhood, Nirvana and being one of the biggest rockstars on the planet.

DAVE GROHL is many things to many people, among them drummer, frontman, producer, record-label owner, amateur comedian, husband, and dad. If you get the chance, though, you really should experience one of his lesser-known guises: chauffeur.

DAVE GROHL is many things to many people, among them drummer, frontman, producer, record-label owner, amateur comedian, husband, and dad. If you get the chance, though, you really should experience one of his lesser-known guises: chauffeur.

It's a sunny February afternoon at Studio 606, the Foo Fighters' sprawling complex in California's San Fernando Valley, and Grohl, 42, is showing me around the place, pointing out items of particular interest to anyone who's followed his decades-spanning musical career. Upstairs in a gear-stuffed loft space, there's the enormous vintage mixing

board he used to record the first Foo Fighters record, not long after Kurt Cobain's 1994 suicide brought about the end of Grohl's old band, Nirvana. There's a long hallway decorated with dozens of

gold and platinum plaques. And stacked against a wall in an imposing two-story tower are countless cardboard boxes that Grohl estimates hold at least 100,000 unsold CDs by his now-dormant heavy-metal side project, Probot.

Outside, in the 606 parking lot, Grohl proudly displays his latest acquisition: a white 1989 Cadillac Van Cleef limousine complete with perioc detailing, including an enormous mobile phone, and some grim-looking beige carpeting. (There's also a bottle of Crown Royal that appears to have been there since the Reagan Administration.) The Foo Fighters purchased the vehicle to use in the willfully old-school music video for "White Limo," a hard-rocking cut from the band's new album, Wasting Light. But now it's just sitting here, waiting-begging, practically-to be taken for a spin. As Grohl slides into the driver's seat, he explains that the $10,000 the Foos shelled out for the car wasn't much more than it would've cost to rent a similar conveyance. Whatever its price tag, you get the sense that he probably wouldn't have minded spending more: Dude's totally stoked on this thing.

Soon we're rolling through the vaguely seedy neighborhood that surrounds Studio 606, taking in the scenery while Grohl demonstrates the limo's exquisite handling. "Fucking smooth, right?" he asks, and indeed the ride is nice-so nice that the brake shops and El Polio Locos around us begin to take on something of a dreamy, sun-kissed sheen. At a stop light Grohl runs through the various interior lighting options at our disposal; he settles on an especially romantic setting that puts him in a generous mood. "It's like date night in here," he says, rounding a corner with expert efficiency. "If you ever need a new place to fuck your wife, just call me."

According to Grohl's pals, going the extra mile is kind of his thing. "Great guitarist, great drummer, great singer-what more do you want?" asks Motorhead growler Lemmy Kilmister, who mans the Van Cleef's wheel in the "White Limo" video. "Dave has shown the world it's possible to be a success and a nice guy at the same time." Kilmister remembers opening for the Foo Fighters at London's Hyde Park in 2006. "After playing in front of 96,000 people, he was the perfect host, flipping burgers backstage."

"Dave is like Bill Clinton," adds Bob Mould, the veteran alt-rocker whose bands Husker Du and Sugar were early influences on Grohl. "Amazing people skills. And he never forgets anyone's name." Last year the two men hung out at

20th-anniversary concert for the 9:30 Club in Washington D.C., where the Foos' frontman got his start with the hardcore band Scream; a few months later, Grohl asked Mould to contribute guitar and vocals to Wasting Light's "Dear Rosemary." "He didn't have to do that," Mould says. "But Dave's in this position now where he wants to share the riches of his success. He wants people to know about the artists who've made an impact on him. It's really touching."

Twenty years after Nirvana's Nevermind turned Grohl into a public persona, that success may still be building. In 2009, before the Foo Fighters got to work on Wasting Light, he flexed his considerable networking mojo by forming a new group called Them Crooked Vultures with Josh Homme of Queens of the Stone Age and former Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones. Earlier this year, the NME presented Grohl with its annual Godlike Genius Award. And in July the Foo Fighters - the band also includes guitarists Chris Shiflett and Pat Smear, bassist Nate Mendel, and drummer Taylor Hawkins - are scheduled to play two sold-out concerts at the 65,000-capacity Milton Keynes Bowl in England. Basically, if you're looking for a bigger rock star these days, you'd better start with a member of U2 or the Rolling Stones.

Yet Wasting Light doesn't sound like the work of someone who sits around polishing his guitars with hundred-dollar bills. For one thing, it's really good - far better than the seventh studio album of most

bands, with expertly crafted tunes that hold their own against earlier Foos hits such as "My Hero,""Everlong"and "All My Life"But it's also remarkably free of the kind of self-satisfied bloat that guys in Grohl's position so often fall prey to; there's a taut, back-to-basics urgency to songs like "Bridge Burning" and "Miss the Misery."

The return-to-roots vibe of the new album hasn't arisen spontaneously. Although the band recorded their last disc, 2007's Grammy-winning Echoes,Silence, Patience & Grace, at Studio 606, Grohl decided to make Wasting Light closer to home, literally: With what he describes as the blessing of his wife Jordyn (with whom he has two daughters: Violet, 5, and Harper, 2), the frontman built a studio from scratch in his garage, then hired Nevermind knob-twirler Butch Vig to produce the album. Former Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic even makes an appearance on "I Should Have Known," a slow-burn power ballad featuring one of Grohl's most intense vocal performances ever. Last October Grohl posted a photo of himself with Vig and Novoselic on the Foos' Twitter feed. The caption? "Three amigos."

Grohl had reconnected with Vig for a couple of tracks on the Foo Fighters' 2009 greatest-hits set; the chemistry was still potent enough that Grohl told the producer he'd love to work together again. "So he calls me and says he's got some stuff he wants to play for me," Vig recalls. "I get to his house and the first thing he says is, 'I really wanna do this in my garage.' So we went downstairs and set up a snare drum. I said, 'Well, it sounds really loud and trashy, but I don't see why we can't do it.' Then he said he wanted to record on tape with no computers. That threw me for a loop; I've made lots of records that way, just not for the last 10 years. But Dave really wanted it to be about the sound and the performance. They'd just played some shows at Wembley Stadium, and he told me, 'We've gotten so huge, what's left to do? We could go back to 606 and make a big, slick, super-tight record just like the last one. Or we could try to capture the essence of the first couple of Foo Fighters records'"

"I think environment is extremely important to Dave," says Academy Award-winning director James Moll, who filmed much of the recording process for a forthcoming documentary about the band. "Not just in terms of place, but the people who are around him. Doing this album in his garage with his family nearby - that was a big deal for him. And it paid off: Everyone in the band really seemed to enjoy making the record. When one player was doing his parts, the other guys would usually be around. It was laid-back, but at the same time it was obvious how committed and hardworking they are."

Casual in a plaid flannel shirt, dark jeans, and sneakers, Grohl acknowledges his desire to tap into that spirit of the early days as we sit down for a chat in the control room at Studio 606. Yet as Moll suggests, the rawness of sound afforded by concrete floors wasn't the only reason the guy built a studio at his house. For Grohl, the work ethic Moll describes extends well beyond the Foo Fighters.

How does being a musician at 42 differ from what it was like when you were in your twenties?

How does being a musician at 42 differ from what it was like when you were in your twenties?

At this point I actually try to do as little as I can, so I can have a life outside the band. There's always great opportunities, like playing a festival or touring some part of the world or playing on somebody else's record. And I understand and appreciate how fortunate we are to be able to pick and choose. But at the end of the day, the first priority, the slice that I cut out first, is always family shit. I mean, also, I've been on the road since I was 18 years old - that's kind of a long time.

Your being away must be a little easier for your kids because this is the only life they've ever known for you. It's not like you used to work at Best Buy and now you do this.

Right - I didn't win the lottery after they were born; I won it when I was 22. They understand. One of Violet's favorite books is Richard Scarry's Busy, Busy Town. It talks about different people and their jobs and what they do. Early on I said, "You know, Violet, some daddys are pilots and firemen and policemen and lawyers. I'm a musician, that's what I do. I go out and work so we can have money to eat and buy you clothes."

And she gets it. When I tell her I have to go to the studio, she knows it's work. And when I'm on the road away from my kids, I really miss them a lot. But I also understand, like, I kind of have to be a dude about it. I can't be such a fucking puss that I cry every time I hit the road. As much as I love it and it's super-fun, it's also my job, you know?

Has it been difficult to make the two halves of your life coexist?

I always imagined that the music thing would stop. To this day, I think, OK, well, this is probably our last record. After this I'll find something else to do and I can relax and take care of the kids. It used to be that I imagined this would just end, and then I'd settle down, stop playing music, and start this whole new life of just being a domestic father. Then I had this Neil Young epiphany when we played one of one of Neil's Bridge School Benefits [the proceeds of which go to the Bay Area organization for kids with disabilities]. The night before the gig Neil had this big barbecue at his house, and we drove the 10 miles through his property to this little house in the woods, and there's [Young's wife] Pegi in the kitchen making dinner. There's the kids hanging out. And there's David Crosby smoking a bowl by the fireplace. It just seemed like, Oh, wait-you can do both at the same time. You just have to find your way to do it.

Did you always envision yourself with a family?

When Jordyn and I first got married, she kind of said, 'OK, well, should we have babies now?' I grew up with a really cool family. I have a fucking rad father who's a writer and a classically trained musician and funny as shit. My mother

is this incredibly loving and wonderful English teacher. And my sister, we kind of went through our punk rock phase together. So I never had any aversion to growing up and becoming a parent, because I liked mine-they were fucking cool. But I thought, Well, let's wait first and see what happens. Then we started going for it, and my biggest concern was raising a kid in Los Angeles. I'm from Virginia, where my public school was across the street from my house.

And it was probably good.

It was great! I mean, I dropped out, but that was my bad. It was just hard for me to imagine someone having any sort of stable, realistic existence in Los Angeles. But my wife, she's born and raised here in the Valley. I look at her and I'm like, Really? You seem like you grew up in Indianapolis. She's super-straight and super-smart and super solid. And I started to realize one of the reasons why she was OK is that she was surrounded by good things. She had family. And kids learn everything by example. Watching the dynamic of loving relationships, that's just how they figure shit out. And that becomes the foundation of their emotional growth for the rest of their life.

If it surprises you to hear that kind of grown-up talk coming from a guy eager to dispense his recipe for buffalo chicken dip - let's just say it involves an entire tub of whipped cream cheese -there's a lot more where that came from on Wasting Light. On "These Days" Grohl warns a younger counterpart (perhaps himself?) that, sooner or later, "the ground will drop out from beneath your feet" and "your heart will stop and play its final beat." The Nirvana-ish "Back & Forth" finds him examining "another life...back when I was new." And in Walk," the album's closer, he sings of wanting "to keep alive a moment at a time" over pummeling power chords. It's an album about coming to grips with your past in order to better navigate your future, which doesn't mean it lacks for killer grooves (check out "Rope") or riffs designed for the youth of a nation to bang their heads to ("Arlandria").

"When you do something of great note, that's where people want you to stay," Mould says in reference to Grohl's time with Nirvana, one of the few groups all music fans can agree Changed Pretty Much Everything. "And I don't know if Dave was making a conscious effort or not, but this record kind of sounds like he's reconciled something with himself - like he's gotten to a point in his life where he knows what people want from him and he's OK with that."

"When you do something of great note, that's where people want you to stay," Mould says in reference to Grohl's time with Nirvana, one of the few groups all music fans can agree Changed Pretty Much Everything. "And I don't know if Dave was making a conscious effort or not, but this record kind of sounds like he's reconciled something with himself - like he's gotten to a point in his life where he knows what people want from him and he's OK with that."

Grohl is well aware that the way he chose to make Wasting Light will invite comparisons to Nevermind. "The expectations this time are kind of high," he says. "There's a lot riding on this record. 'Oh, you're gonna make the record with Butch Vig? What, you think you can make that Nirvana record again?' It's just setting the band up to be fucking torn to shreds. But that challenge is kind of what I'm into."

"I think that pressure was good," says Vig. "It made us focus on the songs and strip away everything extraneous. We put in long hours; everyone had to be on their toes, and there was sort of a no-bullshit factor. But, I mean, Dave can be a total goofball, too. We laughed so much during this record."

Given Cobain's tortured lyrics, it's easy to assume that when Nirvana recorded with Vig, those laughs were few and far between. Not according to Grohl. "Dude, Nevermind - those were the happy days!" he says. "We were in fucking L.A., destroying hotel rooms, getting drunk every night, going to the Palladium to see the Butthole Surfers." Things did darken as Nirvana's fame exploded, though, and that experience, Grohl says, shaped the decision-making process he's employed ever since.

"The basis of my musical personality was so simple," he explains, recalling his time on the D.C. punk scene. "All you do is make songs with your friends, then go record them in your other friend's studio. Then you stuff the records into sleeves and sell them out of your car. Later, when I saw how complicated it could be, I just thought it was totally unnecessary. Yeah, the machine was a lot bigger, but it's basically the same process, and everything else just seemed kind of silly. When someone would

say, 'You guys have the number one record in the country,' I was like, 'Rad!' Why should that be any more difficult than it has to be?"

Grohl says Studio 606 is like a "fortress" for the Foo Fighters, and that it's provided them with a valuable refuge from the complications that can sink a megapopular rock band. "We've gone through our share, whether it was drugs or Hollywood bullshit or just basic lameness," he says. "But we've never been swallowed up by it. All you have to do is turn it off."

Taylor Hawkins credits a portion of the band's ability to do that to the Foo Fighters' relatively slow ascent. "We've never had the 10-million-selling album" he says one night, following a soundcheck at the Roxy theater in L.A. "That makes it easier to kind of keep your priorities in check."

As someone who knows a little more than his bandmates do about overnight success, Grohl places less emphasis on that explanation. He thinks it's about trying to treat your band like you do your family-even as you work to prevent the former from eclipsing the latter. "We all watched James's documentary together a few nights ago," he says. "And at the end of the movie the lights came up and I just looked around at everyone and I was like, 'Holy shit-l can't believe how long I've known Nate.' And then I thought about how many gigs Pat and I have played together, how many funerals we've been to together. That bond is more than the new single. It's something else, and I think that's one of the main reasons we're still here."

How long will that remain enough to keep the good ship Foo afloat? Grohl can't say. But he's not worried.

"The most important thing to me is that we do what's right, we do what's real, and that we're a fucking blazing live band," he says. "When I show up at a festival and we're the headliners, and I've got gray hair in my beard, I want the kids who played the 12 slots before us to look at us and be like, 'Damn, those guys are old-but, fuck, they're really good.' To me that's a good thing. I wanna be the older guy."

DAVE GROHL is many things to many people, among them drummer, frontman, producer, record-label owner, amateur comedian, husband, and dad. If you get the chance, though, you really should experience one of his lesser-known guises: chauffeur.

DAVE GROHL is many things to many people, among them drummer, frontman, producer, record-label owner, amateur comedian, husband, and dad. If you get the chance, though, you really should experience one of his lesser-known guises: chauffeur. How does being a musician at 42 differ from what it was like when you were in your twenties?

How does being a musician at 42 differ from what it was like when you were in your twenties?  "When you do something of great note, that's where people want you to stay," Mould says in reference to Grohl's time with Nirvana, one of the few groups all music fans can agree Changed Pretty Much Everything. "And I don't know if Dave was making a conscious effort or not, but this record kind of sounds like he's reconciled something with himself - like he's gotten to a point in his life where he knows what people want from him and he's OK with that."

"When you do something of great note, that's where people want you to stay," Mould says in reference to Grohl's time with Nirvana, one of the few groups all music fans can agree Changed Pretty Much Everything. "And I don't know if Dave was making a conscious effort or not, but this record kind of sounds like he's reconciled something with himself - like he's gotten to a point in his life where he knows what people want from him and he's OK with that."