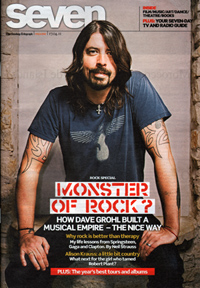

Sunday Telegraph 'Seven' magazine

'The Nicest Man in Rock' on endless touring, the legacy of Nirvana and what he'd do to protect the Foos

'The Nicest Man in Rock' on endless touring, the legacy of Nirvana and what he'd do to protect the Foos

Is Dave Grohl, leader of Foo Fighters and former drummer with Nirvana, The Nicest Man In Rock? Everyone – journalists, other musicians, his mother – says he is. But is he really? Here’s the case against. For one thing, these days he may be a happily married father of two, but after his first marriage ended, he had a John Lennon-style “Lost Weekend”.

“I moved to Los Angeles for one year in 1997. That was post-divorce,” remembers the 42-year-old who, via his two Nirvana albums and six Foo Fighters releases, can lay claim to record sales of 25 million copies. He didn’t lose himself in a haze of drug abuse, “but I did all of the other things...”

So, he’s a sleazeball. Well, he was. Briefly. Fourteen years ago. “And that’s it. That was enough for me, that one year. Because how could that possibly make you feel fulfilled? That momentary reward isn’t enough.”

More evidence for the prosecution: Foo Fighters have been chugging onwards, pumping out sturdy pop-rock hit singles (This Is A Call, Everlong, Times Like These) since 1995, the year after Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain shot himself. But they’ve had a revolving door of personnel in that time. The man responsible for the hiring, firing and retiring of a fistful of guitarists and drummers? David Eric Grohl.

This merry-go-round is recounted in wincing detail in Back And Forth, a new documentary about the band. It is being released in cinemas in parallel with the appearance of the latest Foo Fighters album, Wasting Light. However, all the ex-members of the band were happy to be interviewed for the film. If grudges are held, they’re outweighed by the musicians’ continued respect for their erstwhile leader. Plus, to his credit, Grohl admits he found it “abso-fucking-lutely uncomfortable watching the film”.

Did he feel guilty? “Totally. Yeah, it was hard – but it’s a true story so why not tell it?”

The Los Angeles-based singer, songwriter and guitarist says that his “territorial” protection of his band is what led him, for example, to re-record all the drums himself on Foo Fighters’ second album, The Colour And The Shape (1997), much to the distress of the band’s then-drummer (cue drummer walking out). “I did it because I knew the album wasn’t going to make it unless I did.” Thus, paradoxically, protecting the band is what makes him get his “claws out”?

“Absolutely,” he nods vigorously, pointing out that the current line-up of the band has been unchanged for five years. “I mean, I never liked being told what to do. It’s one of the reasons I dropped out of school. Give me something to assemble, I won’t look at the directions, I’ll try to figure it out by myself. It’s why I love Ikea furniture.” The prosecution rests, and will proffer a plea bargain. The evidence suggests that Grohl may indeed be The Nicest Person In Rock, a smart, candid, respectful, generous, enthusiastic purist. He even loves Ikea.

My month shadowing Grohl and his bandmates (guitarists Pat Smear and Chris Shiflett, bassist Nate Mendel, drummer Taylor Hawkins) begins one February night at the plush premises of the British Academy of Film & Television Arts in central London.

Bafta is hosting a screening of Back And Forth. As a piece of “rockumentary” film-making goes, it exhaustively grills the band about their relationships with each other – in the words of the singer, there are few “wacky tour anecdotes”. In unflashy detail, and via archive footage and new interviews with the band conducted by the director (“I did 14 hours!”), it details Grohl’s musical history: pre- Nirvana, when he was in punk bands in Los Angeles and Seattle; joining Nirvana in 1990, prior to the recording of their landmark second album Nevermind; his “crash course in rock”, between 1991-94, when the trio, contrary to anyone’s expectations, became the biggest band in the world; the horror of Cobain’s descent into heroin addiction and his suicide, 17 years ago, at the age of 27.

As the nearly two-hour film zips onwards, we see Grohl’s re-emergence as a

gifted writer and frontman in his own right. It was more than anyone

expected from the

drummer dubbed “grunge Ringo” – even if he had been

fundamental to the success of a band that reshaped what “alternative rock”

meant.

drummer dubbed “grunge Ringo” – even if he had been

fundamental to the success of a band that reshaped what “alternative rock”

meant.

Then we follow 16 years of roaring success – in support of their last album, 2007’s Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace, Foo Fighters sold out two nights at Wembley Stadium; that’s 170,000 tickets – and some occasionally troubling inter-personnel trauma. After the screening, the band file into the Bafta bar. Strapping, well-preserved Grohl is dressed, as is his is wont, in a rock-oriented T-shirt (Motorhead), jeans and trainers. His shiny hair is shoulder-length, his goatee neatly trimmed; his tattooed forearms are meaty, his teeth bright, white and big.

The following night, Foo Fighters are guests of honour at the NME Awards at Brixton Academy in south London. Grohl is being honoured as 2011’s “Godlike Genius” by the music magazine. Towards the end of the boozy bash, Roger Daltrey presents Grohl’s award. The Who frontman introduces Grohl by saying he’d heard “the sound of knickers hitting the floor when Dave walked in the room”. A sheepish Grohl concludes a short speech by saying “this one’s for Kurt”. When I ask why he said this, he replies: “Because can’t you imagine that he would have had that award years ago? So yeah, I was sharing it with him.”

At the close of the ceremony, Foo Fighters were expected to play a short set of four or five songs. They began with Daltrey joining them on a cover of The Who’s Young Man Blues. They ended, two and a half hours later, with Grohl playing another huge guitar solo.

The next night, they turn up at the invitation-only opening of an exhibition dedicated to Queen, being held in an old brewery in Shoreditch. Grohl, a rock Anglophile whose earliest music obsession was Led Zeppelin, admits to being a fan.

Roger Taylor and Brian May, the two active/alive members of the band, also turned up. But, Grohl tells me afterwards, he didn’t enjoy it so much. “I wanted to be this anonymous Queen fan, walking around and taking it all in, with the headphones on. But I wound up having to pose for a picture with everybody and their mother. So I gave up after about an hour.”

I next see Foo Fighters in mid-March. They’ve come to Austin, Texas, to SXSW (South By Southwest), a music festival for, mainly, up and coming “buzz” bands. There is also a film strand, and the LA-based five-piece are here to premiere their documentary. And while they’re here, they might as well do another secret show. They play for almost two hours behind a rib shack called Stubbs. The second song is new single Rope, which already sounds like a classic Foos anthem.

The following afternoon, the band are in a stone-built, 90-year-old scout hut in a country park a little way from the centre of town. Grohl is buzzing. Happy to be on the road, happy to be talking about a new record,thrilled to be launching it at SXSW. That said, he is missing his children. Violet is four and Harper is 18 months old. Jordyn, the wife he met 10 years ago and a former MTV producer, is used to his extended absences. But having a young family was one reason he decided to make Wasting Light at home, in his garage. The documentary’s final portion sees these recording sessions, with walk-on parts for his children.

“I love everything about my job, except being away from the kids. This,” he says, showing me a chunky gold ring with his initials on it, “the day I was leaving, my daughter said, ‘Daddy, I want you to wear this. And every time you miss me, look at this ring and just know that I love you so much’. She’s not even five! I was blown away.”

Grohl is a renowned workaholic – he has participated in numerous musical side-projects, and one of the themes of Back And Forth is just how long Foo Fighters spend on tour.

Does having a young family make him use his time more efficiently? “Yeah. I was talking to my mother about this the other day. She was a public school teacher for 35 years, so she worked. And I was driving to the studio – because even on our time off, it’s not time off – I’m in there every day, 10 in the morning, doing stuff. I’m president of Foos Inc, that f------ corporation!”

His mother, who now lives near him in LA, was worried he worked too hard. He had to tell her that was how she’d raised him. After his parents divorced when he was seven – his father was a political speech writer in Washington DC – money was scarce. Hard work was ingrained.

In any case, Grohl points out as we talk on a windy terrace overlooking Austin: “How could you not want to do this? I get to sit around and talk about rock’n’roll all day, then go play music with my friends and laugh my a-- off backstage, until it’s time to have a beer and get 80,000 people to sing with me. That’s not work!”

Does Violet understand what her father’s job is?

“Absolutely. We have this Richard Scarry book, Busytown. Joe’s a plumber, Joe fixes your pipes when they’re blocked. This is a lawyer, he helps people settle arguments.” One day two years ago, Grohl had to go to the “office”: 606 Studios, Foo Fighters’ huge rehearsal and recording facility in Northridge, 45 minutes’ drive from West Hollywood. “And I said, ‘OK, Boo, I’m leaving’.”

“‘Where are you going?’”

“‘I’m going to work’.”

“‘Why?’”

“‘Well, some daddies are lawyers, some are doctors – I’m a musician, that’s my job. And I go to work so that I can make money so we can have food and you can have clothes and you can have toys’. And she immediately said, ‘I don’t have enough toys!”’ Grohl laughs uproariously.

“But I have little tricks – if I’m gone for 10 days, I’ll write 10 letters, and every day I’m gone, my wife gives them a letter. Or I make a calendar and I’ll let them draw the pictures. I left high school at 17. I was on the road on my 18th birthday. And my mother watched me jump in a van with five other dirty punk rockers, and I’d say, ‘OK, I’ll be back in two months’. Called her once or twice from a payphone, sent her a postcard.”

Pause. “I would never let my child do that!”

His life, he says, revolves around two families: the band, and his wife and kids. They, and his closeness to his roots, kept him grounded when he might have been expected to lose it in the manner of so many rockers before him.

“When Nirvana became popular, you could very easily slip and get lost during that storm. I fortunately had really heavy anchors – old friends, family. And if I ever felt like I was being swept away, I’d just run back to Virginia. Drinking at the rib restaurant with my buddies, and the bartender I went to high school with, that’s what kept me from losing it.”

Also, he has perspective on the destructive force of drugs. He lost Cobain, and he almost lost Taylor Hawkins. The Foo Fighters drummer overdosed in London in 2001 and Grohl sat with him until he came out of his coma. “A part of me resented music for doing this to my friends. I just felt like, ‘I don’t want to play any more if it’s gonna make my friend die’.” He seriously thought about giving up music? “Absolutely!” Grohl says forcefully. “When he woke up, I said, ‘Dude, I just want you to know, we’re not talking about the band until you’re ready.’ And we didn’t for a while.”

His inner-strength, he acknowledges, had been forged early on. And, in a way, out of necessity. “I stopped doing drugs when I was 20. I was finished with drugs before Nirvana even started. And I didn’t do hard drugs. I saw it as something that would make everything a little more difficult.

“I also know myself well enough to keep out of that. As soon as I get my face in a pile of coke, it’s game over – teeth out, money gone. You see the way I drink coffee! It’d be all over!” he laughs.

“Plus, I’ve seen it before – before I was in Nirvana I knew people who had OD’d. I love to play music. So why endanger that with something like drugs?”

What kind of 44-year-old does Grohl think Cobain would have been? “I don’t

know,”’he says a little heavily. “He’d probably be the same 25-, 26-year-old

he was. Unfortunately we’ll never

know.” Talking about Cobain is the one

time his natural ebullience levels off. Next month is the 20th anniversary

of the recording of Nevermind. Grohl admits the memory of those more

innocent times still looms large in his thoughts.

know.” Talking about Cobain is the one

time his natural ebullience levels off. Next month is the 20th anniversary

of the recording of Nevermind. Grohl admits the memory of those more

innocent times still looms large in his thoughts.

As does, it seems, Cobain’s widow Courtney Love, with whom there is no love lost. The infamously ranting sometime-musician has variously claimed that Grohl used to repeatedly “hit on” her; that Cobain “loathed” Grohl; and that he wanted him out of Nirvana.

In a manner more legal than gutter, Grohl and Krist Novoselic have clashed with Love over the commercial use (and abuse) of Nirvana’s music and Cobain’s legacy, most recently over a Cobain avatar that appeared on computer game Guitar Hero 5. On the Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace song Let It Die, Grohl sang of “a simple man and his blushing bride/intravenous, intertwined” – widely seen as a reference to Kurt and Courtney.

Today, mention of Love makes him grit his teeth, but he leavens his scant comments with humour. “Can I describe my relationship with Courtney in three words? No. I. Can’t!”

Grohl says he continues to dream about his former bandmate. Making Wasting Light with producer Butch Vig (who worked on Nevermind) and having the band’s bass player Novoselic guest on a song, “brought back some really funny memories. When you’re with people who were there at the same time, you feel like you’re there again.”

Are the dreams musical? “No,” he begins. “Well, I’ve had a few dreams where Kurt shows up and I’m so blown away. ‘Wait, you never died?’ For whatever reason, he’d just been hiding.” He smiles, a little. “And the three of us get together to be a band again.” He pauses and frowns. “It’s totally weird.”

The afternoon ahead is packed with media engagements. In the evening, Foo Fighters are premiering Rope on an MTV show being filmed live in Austin. Then it’s home to LA for a while. On the horizon: a summer of touring, including two sold-out performances at Milton Keynes Bowl. Until then, Grohl will slip back into his domestic role.

“There have been times in LA when I’ll be in a farmers’ market with my wife and we’re sitting down away from everyone, and she’s breastfeeding our child – and paparazzi are taking pictures of her breastfeeding! If I didn’t think I’d get sued I’d murder that person. How dare anyone do something like that?”

The Nicest Guy In Rock is angry. Time to wind him up further. Recently there was a statistical analysis of the kind of songs that had been successful in the charts in 2010. For the first time, r&b and pop dominated, at the expense of the musical form that has occupied most of Grohl’s waking – and sometimes dreaming – thoughts since his adolescence.

So, does Dave think rock is dead? He scoffs. “They say that every year. What, it’s dead again?” He grins his toothy grin. “Ask the 130,000 people who bought a ticket to Milton Keynes if they think rock is dead. I don’t. It’s not dead to me. Never has been.”

Words: Craig McLean