'Let Me Entertain You...'

Q

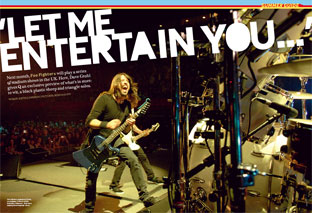

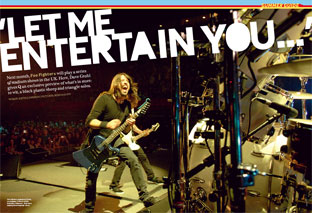

Next month Foo Fighters will play a series of stadium shows in the UK. Here, Dave Grohl gives Q an exclusive preview of what's in store: to wit, a black plastic sheep and triangle solos

Surrounded by a capacity audience at The Forum in Inglewood, Los'Angeles, Dave

Grohl raises his hand for quiet, Just into the second hour of its second night, the Foo Fighters' stint at this venerable arena is about to reach its defining moment.

Surrounded by a capacity audience at The Forum in Inglewood, Los'Angeles, Dave

Grohl raises his hand for quiet, Just into the second hour of its second night, the Foo Fighters' stint at this venerable arena is about to reach its defining moment.

The band has decamped from the main stage to the B stage, a circular plinth that descends lunar module-style from the roof and switches the show's focus to the rear of the auditorium, Already, the band have run the gamut of arena-rock components: the lengthy drum solo from Taylor Hawkins; guitar duels between Grohl and Chris Shiflett, complete with overwrought facial contortions; Grohl's multiple entreaties to "Sing it, you motherfuckers", invariably issued from a vantage point somewhere along the 200-foot-long catwalk that now serves as a link to the B stage. By now, these 15,000 fans might reasonably feel they have seen it all. If so, they are mistaken.

"I'll tell you what we're gonna do tonight that we didn't do last night because we wanted to save it for you fuckers," says Grohl, his mock master of ceremonies spiel fashioned somewhere between Vincent Price and a carnival huckster. "Laydeez and gen'lemen - Drew Hester!"

The Foo Fighters' percussionist takes the B-stage spotlight, wielding the most ridiculed instrument at his disposal. "Look at the triangle guy!" screams Grohl. Hester giggles as he dangles his three-cornered weapon. "When was the last time you came to The Forum and saw a fuckin' triangle solo?"

As he'll later attest, Drew Hester isn't really a percussionist. He's a respected session drummer and producer, who has played with the likes of Joe Walsh, Stevie Nicks and Lisa Marie Presley. An auxiliary member of the Foo Fighters since 2006, he gets the biggest cheer of the night simply by beating seven bells out of a triangle, He admits that his talents have been more creatively employed.

"But playing with this band is the most fun I've ever had in music," he says afterwards,

as well-wishers start piling into the Foo Fighters' dressing room. "The best times, the best people." The reason for this, he reckons, is simple: "It starts from the dude at the top."

As if by magic, the dude at the top enters and surveys the scene. Still wearing the same black sweatshirt,jeans and sneakers he's sported all day, Dave Grohl starts negotiating his way politely through the room. With three-quarters of the core Foo Fighters line-up resident in the Los Angeles area,

this counts as a hometown gig. Friends and family are scarfing food and drink, lounging around what used to be the changing rooms of the LA Lakers basketball team until they left The Forum for LA's shiny new downtown arena, the Staples Center. The homely mix is sprinkled with LA rock stardust - Lemmy, Juliette Lewis, Red Hot Chili Pepper Chad Smith, former Germs and Nirvana guitarist Pat Smear, himself an erstwhile Foo Fighter and now back in the fold as a member of the band's extended eight-person line-up - but Grohl is making his way to the far corner, where he's spotted Pete Stahl.

The singer in Grohl's first serious band, suburban Washington, DC hard core punk outfit Scream, Stahl has known Dave Grohl for 20 years. Since playing drums behind Stahl to tiny crowds on European squat tours and sharing sweat space in crippled vans on marathon hauls across the US. Grohl's rock'n'roll journey has taken him far, sometimes at terrifying speed. Now, after 13 years leading the Foo Fighters it has brought him, quite improbably, to an exalted place among rock's elite.

"Scream were the outcasts in the Washington, DC scene," says Grohl, sipping beer from a plastic beaker. "I'm proud that people consider the Foo Fighters to be unhip, because we were all outcasts to begin with."

In June, the Foo Fighters play two nights at Wembley Stadium and a night in Manchester; the tickets for the London shows sold out in a day. Selling out two nights at The Forum, an iconic American concert venue, earns them the traditional honour of a plaque in the venue's entrance hall, where it will stand among arena titans past (Phil Collins) and present (Pearl Jam). It's nothing if not an acknowledgement of their induction to a select rock pantheon.

In June, the Foo Fighters play two nights at Wembley Stadium and a night in Manchester; the tickets for the London shows sold out in a day. Selling out two nights at The Forum, an iconic American concert venue, earns them the traditional honour of a plaque in the venue's entrance hall, where it will stand among arena titans past (Phil Collins) and present (Pearl Jam). It's nothing if not an acknowledgement of their induction to a select rock pantheon.

Yet this is arena rock with a human touch: no costumes, no pyrotechnics, just the music and Dave Grohl's ability to communicate a sense of solidarity between performers and audience. "Anyone who's never seen us

before, you're lucky!" he regaled the first night crowd. "This is not the bargain show, this is the two-hour rock show. Everybody who has to go to work tomorrow, you're gonna be fucked!"

The response from an audience happily accommodating both tribal hard-rock constituencies and civilians, is unequivocal. They haven't come here for a quiet night of existential contemplation. In the past The Forum has been a sports arena, and today it's also the home to the Faithful Central Bible Church, which draws massive congregations from Inglewood's large African-American population. The building is a shrine to mass delirium. Like the great showman he's become, Dave Grohl knows how this works.

"I think people should be entertained," he says, amid the dressing-room hubbub. "The last thing in the world I want to do is challenge someone with our concert. I want people to feel included in what's going on.

I don't want them to think I'm anything that I'm not, so I try my best to feel completely at ease. I would like for the audience to look at the band and feel like they're looking back at themselves."

If Dave Grohl has managed to retain the human touch in the face of stardom, it's only because he didn't fancy the alternative. In 1992, amid the early stages of Nirvana's crash course in fame, he met Bono after a U2 show on the Zoo TV tour. Bono said he wanted Nirvana to open up for U2 on the tour's North American stadium leg. Grohl, then 23 and still living in the politically correct punk rock interzone of Olympia, Washington, scoffed at the idea. Bono's rock-star persona, however, he found deeply unnerving.

"I was standing in front of a man that had made albums that were a huge part of my life," he says. "But I was saddened by feeling' he had become almost inhuman, that maybe he had become so iconic that there wasn't any way to relate to him as a human being. That freaked me out. I'd love the world to sing our Coca-Cola song in perfect harmony, but I'd hate for anyone to think, That guy's like a fucking mannequin, he's not real."

By now, Dave Grohl has hand-shaken his way around the dressing room to the drinks cooler. He slaps both Q and Pete Stahl on the back. "C'mon, guys. We need to drink whisky."

To get the Foo Fighters machine on the road takes nine trucks, six buses, 35 crew and a large black plastic sheep. The latter stands backstage next to video-screen equipment, wearing an enigmatic expression and a keg of Heineken around its neck.

Right now, however, having just completed the soundcheck for the Foos' second Forum show, production manager Rodney Johnson's concerns are with illumination rather than rumination.

"I've got 1000 amps of lighting in three trucks," says Johnson, a modest, weatherbeaten man tasked with getting this vast superstructure set up, taken down and moved from one place to the next, then making sure it all works. "Two trucks of sound, one each for the A and B stages. I've got one complete set truck. One complete backline set-up for both the A and B stages. And then a rigging truck as well. It takes 55 motors to lift everything up."

While Rodney Johnson does machines, tour manager Gus Brandt does people. From making sure the band's two dressing rooms (the Rock Room and the Family Room) are stocked with the correct brands of nutrition bars (Tigers Milk), peanut butter (365 Organic) and strawberry jam (Smucker's), to getting the Foos onstage on time, Brandt is the man upon whose shoulders rests responsibility for the smooth operation of the rock tour's home away from home.

"There are 100 laminates a day, 200 sticky passes," he says. "Most bands will have four or five guests in their dressing room. Ours is like the United States census. It's not one of those tours where there's four 400lb bodyguards watching the door. It's a lot more relaxed. It's an everyone-come-along vibe. Almost like the Grateful Dead but without the shitty hippy music."

Sleepy-eyed but sharp-tongued, Brandt began working with the Foo Fighters in 1997: one of his first shows was at the Astoria 2 in London, where they made £700. "Now?" He pauses. "We're into six figures a night." He looks impossibly relaxed about the situation, more so than Foo Fighters manager John Silva, Dave Grohl's business ally ever since he took Nirvana under his wing in late 1990. A feisty fount of verbals, Silva has just happened by Brandt's office. His eyebrows stand to attention at the mention of finance.

"We should, uh, make it clear that while the boys make a lot more money, they also spend a lot more money, too," he says.

"Yeah, but y'know what?" replies Brandt with a laugh. "No one's pool is getting cold! Everybody thinks it's funny to get paid for doing this. Even when it's not fun, the worst day working on a tour is still better than the best day working at Topshop. This is like a big weird family. Emphasis on the weird."

No other members of the Foo Fighters family know Dave Grohl better than Ian Beveridge or Jimmy Swanson. Monitor engineer Beveridge is in charge of making sure the musicians can hear what they're playing. As a bonus he gets to clean earwax out of the in-ear monitor systems worn by bassist Nate Mendel and guitarist Chris Shiflett. A genial Scot now resident in the US, Beveridge first met Grohl in 1990 as part of the skeleton crew on what was Grohl's first UK tour as a member of Nirvana.

No other members of the Foo Fighters family know Dave Grohl better than Ian Beveridge or Jimmy Swanson. Monitor engineer Beveridge is in charge of making sure the musicians can hear what they're playing. As a bonus he gets to clean earwax out of the in-ear monitor systems worn by bassist Nate Mendel and guitarist Chris Shiflett. A genial Scot now resident in the US, Beveridge first met Grohl in 1990 as part of the skeleton crew on what was Grohl's first UK tour as a member of Nirvana.

"Dave's always had the same attitude," he says. "I've been on tours where the band won't talk to the crew, or the crew aren't allowed to talk to the band unless it's through one of their 'handlers'. Dave doesn't work like that. He doesn't make people fear him, he makes people like him."

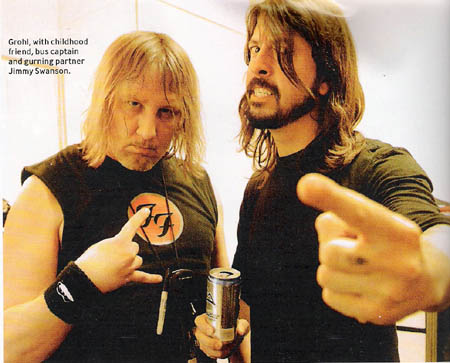

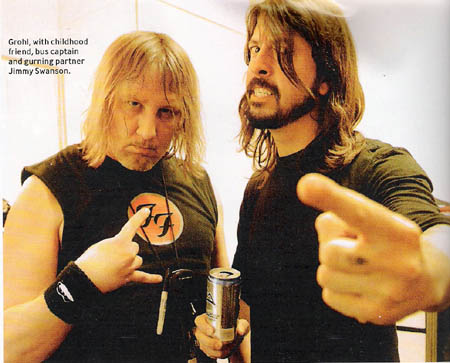

Jimmy Swanson's official role on tour is bus captain, ensuring the Foo tour's fleet is fully catered and ready to go. Unofficially, he is Dave Grohl's music guru. An aficionado of heavy music, with the stringy long hair and cap-sleeve shirts to prove it, Swanson has known Grohl since the pair were five-year-olds in Virginia. They dropped out of high school together and, aged 18, Swanson joined Grohl on his first ever Scream tour. As drum tech, assistant tour manager or bus captain, he has been there or thereabouts ever since. "It's my life," he says, simply.

During his time with Nirvana, Dave Grohl witnessed first-hand how a band's spirit can be corroded by the pressures of fame. The backstage atmosphere on Nirvana tours from 1992 onwards was tense and unhappy. Separate dressing rooms for Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love and the rest of the band were but one symptom of the malaise. That the Foo Fighters tour exudes relaxed bonhomie is no accident. Nor, in the estimation of the man at the head of this organisation, is it incidental to the ongoing success of the band.

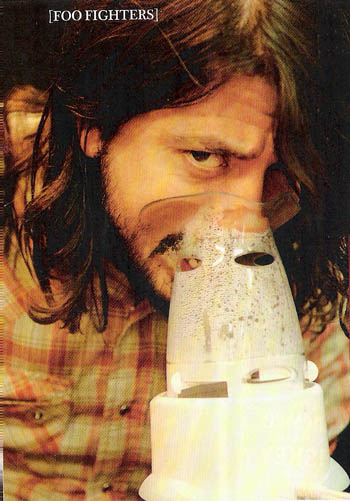

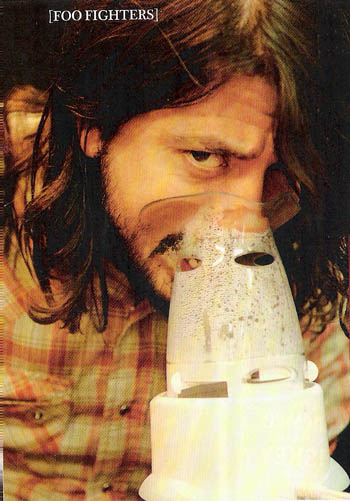

"I don't think there's a lot of selfish people around this band," says Grohl, taking a break from one of his pre-gig sessions with a steam inhaler (effectively a kettle with attached surgical mask, essential for maintaining his voice's capacity to withstand two hours' worth of punishment every night). "We all feel an obligation to each other. It's safety, not only in numbers, but they're like my closest family. If I'm having a weird night and I look round and I see Jimmy on the side of the stage with his Maglite in his hand - he's been there 20 fucking years with the same flashlight - it makes me feel alright."

Less than 48 hours after set-closer Best Of You signed off the second Forum show, Dave Grohl is interrupting a priceless 10 days' R&R between tour legs to talk to Q. He parks his motorbike just down the street from the Sunset Marquis Hotel and asks if we have enough money to buy coffee. The millionaire rock star left his credit cards in his road case after the Forum gig, and they are now en route to Montreal.

Having cadged $40 off his wife the previous day, Grohl set off from his house in Encino this morning for the half-hour drive to West Hollywood, only to realise he was virtually out of fuel. Stopping at the petrol station, he realised he had just $2 to his name.

"I'm like, Whew, at least I have $2... Do you know how much gas $2 buys? A fucking cup! So I just spent my last $2 on gasoline."

It was in the bar at the Sunset Marquis where Grohl met his wife Jordyn in 2001. He marvels at the renovation undergone by the hotel since then. Before he bought a home in the area, Grohl would stay here

on visits to LA. "I actually stayed here with Nirvana once," he recalls. "I'd wake up in the morning and look through the shades to see who was in the pool. Gene Simmons and the Spin Doctors."

Grohl, too, has changed in the 13 years since he formed the Foo Fighters. Back in the early days he deliberately downplayed the extent to which the Foo Fighters' musical vision was his, in order to establish a band identity. Yet the Foo Fighters only really began to blossom once Grohlís personality began to infect his performances as a front man. It was a gradual process, driven by the line-up changes that afflicted the band. First the replacement of drummer William Goldsmith with Taylor Hawkins in 1997; then the departure of Pat Smear, a huge personal blow to Grohl, who lost a friend from the Nirvana days, as well as the Foo Fighter with the most onstage charisma.

Ian Beveridge believes Pat Smear's departure prompted you to compensate for the absence of such a big onstage personality. Correct?

Ian Beveridge believes Pat Smear's departure prompted you to compensate for the absence of such a big onstage personality. Correct?

"Maybe. I don't think I realised how big a personality Pat was until he left. If there was any compensation for his absence it was unintentional. I think it just happened."

You've grown into your current role very gradually, then?

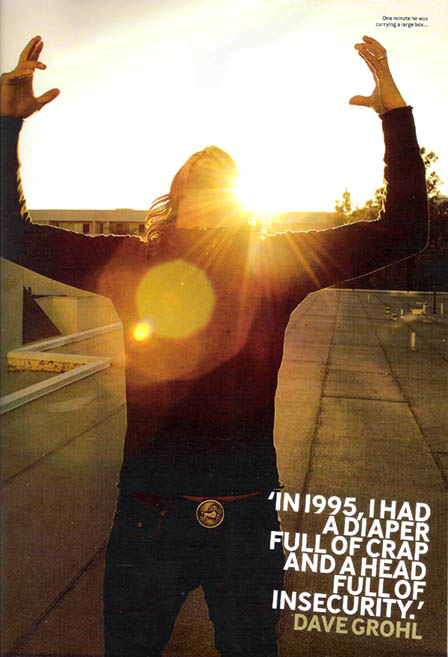

"Absolutely. It took me a long time. I have no problem standing in front Of100,000 people and asking them to sing a song with me. In 1995, I would have had a diaper full of crap and a head full of insecurities. I remember this festival we played in France in 1996.

We were opening up for David Bowie. It didn't make any sense for me, a drummer pretending to be a singer, to stand in front of so many people and try to entertain them all. Like, I'm not Freddie Mercury. And then David Bowie goes out and lifts a fucking finger and people go fucking berserk! I didn't understand it at all. And I think in denying it and being afraid of it, it just made it worse. Eventually, I just didn't give a fuck. Having played so many festivals all over the world, and being placed in front of 50 or 60,000 people a night, you stop thinking about it."

By sheer repetition you surrender a part of your consciousness?

"Yeah, your self-consciousness."

Compared to its past high-water marks, Dave Grohlís reservoir of guilt is diminished these days.

As he sprinted down the catwalk at the Forum, he made with the obligatory gesticulations, playing off one part of the hall with another until all were conjoined in a mindless chorale.

It's a long way from the teenage Grohlís Washington, DC punk scene tutelage from the likes of the likes of Bad Brains and Rites Of Spring, whose proto-emo strafes remain faintly discernible amid the Foos' streamlined earcandy. But like most kids touched by punk, Grohl had a more innocent musical adolescence. From the age of eight, until he discovered punk at 13, his favourite bands were The Beatles, Rush, Led Zeppelin and Kiss ("But I just had the poster, so that doesn't count"). He saw his first arena rack shows Robert Plant, then two weeks later the Monsters Of Rock festival featuring Scorpions, Van Halen and Metallica - at the age of 19. "I was a cynical pothead," he says. "Like, This is stupid, this place is so big. It made no sense. But now, I guess it does."

In his comfortable embrace of stadium rock, Dave Grohl is reverting to a set of core musical instincts temporarily suppressed by punk's militant strictures. Although they released an album on Dischord, the crucible of politically correct US punk, Scream were outcasts. Their maverick musical tendencies (classic rock covers next to high velocity thrash) broke with the scene's orthodoxy. Philosophically, Grohl was neither straight-edge or vegan, a sympathetic outsider rather than a core participant. Then, on joining Nirvana, he moved into Kurt Cobain's apartment in Olympia, an hour south of Seattle, home of ultra-liberal Evergreen State College and the birthplace of riot grrrl, where he found himself involved in a punk scene no less didactic than Washington, DC.

"Olympia was like DC without the fun or the good music." says Grohl. "Everyone was so wracked ,with guilt, musically, just walking on eggshells. 'What a fucking drag. And obviously. we've seen what guilt can do to musicians. I've been thinking about that a lot as we've been doing this arena-rock tour. There's times when I have flashes of guilt, like, [wincing] "Oooh, I seem like Joe Perry up here. God, what am I doing: Iím leading an arena-rock show. There was a time when it was against the rules."

When Q calls Nate Mendel at his home in Portland, Oregon, a few days after the forum shows, he admits that he's been wondering about that black plastic sheep. He sees it backstage every day on tour, serving no obvious purpose. Indeed for the bassist, the black plastic sheep represents a barometer of the surreal trajectory taken by this erstwhile punk-rock band from the Pacific Northwest.

"All of a sudden you've got a crew of people running video screens and you haven't been introduced to them," he says.

Mendel is the only Foo Fighter to have stuck with Grohl throughout the band's 13 years. He pinpoints a segment of touring in 2000 as the moment when Grohl began to step up his game and grapple with the arena rock beast within.

"We went out and opened for the Red Hot Chili Peppers in these arenas, for

the first time playing larger venues over a consistent period of time. It became obvious - OK, the rules are different now, you have to do things differently to project what you're doing to fill that larger space. Dave's sharp and motivated and ambitious: it didn't take him long to go, OK, I know what to do here. He grew into it pretty quickly. That's not to say it was super-contrived: I think Dave's personality fits playing these kind of shows pretty naturally."

Grohl is strapping on his crash helmet as Taylor Hawkins pulls up at the Sunset Marquis in a brand-new black Cadillac XLR convertible. It's a classic testosterone-wagon. but Hawkins's "Hollywood years", as he remembers them wistfully, often spent in the company of Dave Grohl, are long gone. These days, the man who once came close to dying when he overdosed on prescription painkillers after 2001's V Festival, is married and with a seven-month-old son. He's too tired to party.

"I'll tell you, the best thing in the world is having a family. Especially in this racket when we're on tour all the time. Just going home - I know that's where Dave was going now and there's nothing better. We went through our wild times in our 20s, but we're all adults now. We lived to tell the tale!"

&nbp Hawkins's effervescent personality helped recast the Foo Fighters as a rather more relaxed vehicle for adrenalised rock thrill seeking. He encouraged Grohl's garrulous personality to blossom. As his bachelor buddy in the late '90s, he's been well placed to observe his bandmate grow as a performer.

"It took Dave a while to build up that stag ego. I'm not saying he has a huge ego - actually, I'm sure he does, he just doesn't show it! - but an ego enough to commandeer a stage and say, I belong up here. He knows he's good at what he does, but I think he's still as insecure. A lot of times he probably just thinks, God, I'd much rather be sat behind a drum kit."

The morning of July 2007. Dave Grohl is on his way to Wembley Stadium to play the British leg of the Live Earth concert. He has no idea when the Foo Fighters are playing. The organisers have refused to release such information in advance. Two days earlier Foo Fighters had played a secret club gig at Dingwalls, North London. There, Grohl had chatted with Queen's Roger Taylor who confirmed that the new Wembley is huge "fucking huge", actually. "When someone from Queen says a place is big," ponders Grohl, "that means it's pretty fucking big."

The morning of July 2007. Dave Grohl is on his way to Wembley Stadium to play the British leg of the Live Earth concert. He has no idea when the Foo Fighters are playing. The organisers have refused to release such information in advance. Two days earlier Foo Fighters had played a secret club gig at Dingwalls, North London. There, Grohl had chatted with Queen's Roger Taylor who confirmed that the new Wembley is huge "fucking huge", actually. "When someone from Queen says a place is big," ponders Grohl, "that means it's pretty fucking big."

Given the acts who are on the Live Earth bill- including Madonna, Metallica and Genesis - Grohl had assumed the Foo Fighters would be allocated a mid-afternoon slot. On arriving at the stadium, he discovers that Genesis are on first, Metallica at tea-time and that the Foo Fighters are playing I second to last, with only Madonna to follow.

As the day progresses, with one tepid performance following another, Grohl senses a lack of connection from any of the performers to the audience. Then, half an hour before going onstage, he is approached by manager John Silva. "Here's what I need for you to do," says Silva. "I need for you to be better than Metallica."

"I thought, OK!" recalls Grohl today. "That's the most ridiculous thing anyone has ever said to me in my entire life... "

Live Earth was a pivotal moment for the Foo Fighters, a tipping point in the general public's perception of the band. Always more successful in the UK than at home, suddenly millions watching on US TV were confronted by the spectacle of the Foo Fighters slaying 85,000 people at a vast stadium. Sure enough, at the next time of asking, they're selling out arenas across America.

The reason the Foo Fighters stole the show at Live Earth wasn't just that most of the other performances were lacklustre, or that the band played the right songs, but that Dave Grohl knew the audience wanted the affirmatory emotional surge that makes sense of such vast events, and he provided it.

Grohl's eyes-ablaze rendering of Times Like These gave this well-intentioned but vague event a fitting anthem. To anyone watching Grohl for the first time since the earliest Foo Fighters shows, his steely, messianic demeanour would have seemed surprising. Even the self-effacing Grohl can't entirely downplay his achievement.

"We only had to play five songs. So we decided to play the ones that everybody knew! [Laughs] lt wasn't an audition, this was a celebration! And yeah, I felt like I was being challenged by all of the bands before me. I'm not a competitive dude. But I thought, OK, motherfuckers, watch this. I had my wife and daughter on the side of the stage. I was standing there behind the curtain with a guitar in my hand, after four beers, and thought, Fuck it, this is going to be good."

When the Foo Fighters make their return to Wembley Stadium, Rodney Johnson will ensure the stage gets built. Gus Brandt will have lots of sticky passes. Ian Beveridge will enjoy an intimate moment with other men's earwax. Jimmy Swanson will count the buses in and out. There will be a black plastic sheep backstage and no one will have a clue why.

Dave Grohl, however, can't pretend it's just another day at the office. "So what the fuck do we do after two nights at Wembley?"

Although the arrival of his daughter Violet Maye two years ago dictated no more six-month road odysseys, Grohl and the Foo Fighters have been engaged in touring ever since the release of the band's current album, Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace, last autumn. The final date is in mid-August. Yet Grohl's already been asked if he wants to play China in October. "I said no," he shrugs.

The day before we meet at the Sunset Marquis, Grohl had Violet to himself while Jordyn ran errands. They went to a hot-dog restaurant down the street from their house and watched basketball on TV. In the midst of the moment, Grohl got choked up, almost cried. "Because I thought this is exactly what I imagined being a father would be like: hanging out with my daughter, eating hot dogs. Yesterday, I imagined doing that every day for a long time. I could never imagine being one of those bands that takes a year or two away. Until now. So yeah, I'm starting to imagine what it would be like to spend time away from the band."

Then again, rock'n'roll is the only thing he knows how to do. By way of farewell Q asks Dave Grohl what he's doing for Easter. Turns out he'll be in his studio with Lemmy and ZZ Top's Billy Gibbons.

"Look, I'll show you the text Lemmy sent me," he says, holding up his mobile. It reads "Don't make any plans for Easter Sunday or Monday You will be making a rock hysterectomy with the Reverend Billy G and the Reverend Lemmy Kilmister. Better get yourself ordained - quick!"

Grohl smiles. "It's Lemmy, man. You can't say no."

back to the features index

In June, the Foo Fighters play two nights at Wembley Stadium and a night in Manchester; the tickets for the London shows sold out in a day. Selling out two nights at The Forum, an iconic American concert venue, earns them the traditional honour of a plaque in the venue's entrance hall, where it will stand among arena titans past (Phil Collins) and present (Pearl Jam). It's nothing if not an acknowledgement of their induction to a select rock pantheon.

In June, the Foo Fighters play two nights at Wembley Stadium and a night in Manchester; the tickets for the London shows sold out in a day. Selling out two nights at The Forum, an iconic American concert venue, earns them the traditional honour of a plaque in the venue's entrance hall, where it will stand among arena titans past (Phil Collins) and present (Pearl Jam). It's nothing if not an acknowledgement of their induction to a select rock pantheon. Surrounded by a capacity audience at The Forum in Inglewood, Los'Angeles, Dave

Grohl raises his hand for quiet, Just into the second hour of its second night, the Foo Fighters' stint at this venerable arena is about to reach its defining moment.

Surrounded by a capacity audience at The Forum in Inglewood, Los'Angeles, Dave

Grohl raises his hand for quiet, Just into the second hour of its second night, the Foo Fighters' stint at this venerable arena is about to reach its defining moment. No other members of the Foo Fighters family know Dave Grohl better than Ian Beveridge or Jimmy Swanson. Monitor engineer Beveridge is in charge of making sure the musicians can hear what they're playing. As a bonus he gets to clean earwax out of the in-ear monitor systems worn by bassist Nate Mendel and guitarist Chris Shiflett. A genial Scot now resident in the US, Beveridge first met Grohl in 1990 as part of the skeleton crew on what was Grohl's first UK tour as a member of Nirvana.

No other members of the Foo Fighters family know Dave Grohl better than Ian Beveridge or Jimmy Swanson. Monitor engineer Beveridge is in charge of making sure the musicians can hear what they're playing. As a bonus he gets to clean earwax out of the in-ear monitor systems worn by bassist Nate Mendel and guitarist Chris Shiflett. A genial Scot now resident in the US, Beveridge first met Grohl in 1990 as part of the skeleton crew on what was Grohl's first UK tour as a member of Nirvana. Ian Beveridge believes Pat Smear's departure prompted you to compensate for the absence of such a big onstage personality. Correct?

Ian Beveridge believes Pat Smear's departure prompted you to compensate for the absence of such a big onstage personality. Correct? The morning of July 2007. Dave Grohl is on his way to Wembley Stadium to play the British leg of the Live Earth concert. He has no idea when the Foo Fighters are playing. The organisers have refused to release such information in advance. Two days earlier Foo Fighters had played a secret club gig at Dingwalls, North London. There, Grohl had chatted with Queen's Roger Taylor who confirmed that the new Wembley is huge "fucking huge", actually. "When someone from Queen says a place is big," ponders Grohl, "that means it's pretty fucking big."

The morning of July 2007. Dave Grohl is on his way to Wembley Stadium to play the British leg of the Live Earth concert. He has no idea when the Foo Fighters are playing. The organisers have refused to release such information in advance. Two days earlier Foo Fighters had played a secret club gig at Dingwalls, North London. There, Grohl had chatted with Queen's Roger Taylor who confirmed that the new Wembley is huge "fucking huge", actually. "When someone from Queen says a place is big," ponders Grohl, "that means it's pretty fucking big."