Modern Drummer

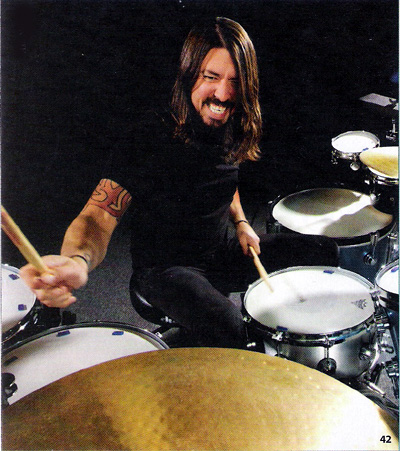

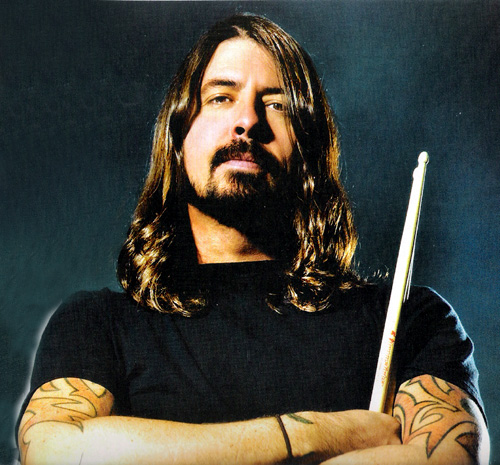

The Foo Fighters leader's career takes yet another compelling detour - this time with Queens Of The Stone Age and Led Zeppelin members in Them Crooked Vultures.

Modern Drummer

The Foo Fighters leader's career takes yet another compelling detour - this time with Queens Of The Stone Age and Led Zeppelin members in Them Crooked Vultures.

Twenty years later, Grohl is arguably the most influential rock drummer since John Bonham. Meanwhile, his songwriting gifts, as expressed in his band Foo Fighters, have shown him to be one of the most influential musicians of the past twenty years as well. Grohl's drumming can smash your skull to splinters and just as easily surprise you with a perfectly placed tom fill or unusual hi-hat accent. Grohl can groove, Grohl can kill, and Grohl can also create.

Always one to recognize a powerful riff and a great melody, Grohl started Foo Fighters after the demise of Kurt Cobain and Nirvana, impressing a wary public with potent pop songs waged over heavy thunder beats (initially performed by Grohl himself, then by best friend Taylor Hawkins). As Foo Fighters' fame spread, so did its leader's wings, as Grohl plied his drumming wares with Nine Inch Nails, Tony Iommi, Killing Joke, Tenacious D, Cat Power, Garbage, Pete Yorn, the Prodigy, Probot (Dave's own metal project), and, perhaps most important, Queens Of The Stone Age.

Impressed by QOTSA frontman Josh Homme's mighty guitar riffs, Grohl drummed hard and heavy on the band's 2002 release, Songs For The Deaf. But in hindsight this was just a warm-up for the Homme/Grohl/John Paul Jones project, Them Crooked Vultures.

With all the experience of a lengthy résumé brought to fruition, Them Crooked Vultures crystallizes the evolution of Dave Grohl and highlights his reinvention as a drummer. Listening to a twenty-two-yea-old Grohl slamming his drums senseless on Nevermind, you'd never guess it's the same dude who crafted the sophisticated drumming sentences and intricate time-bending grooves of the Vultures' self-titled debut disc. Though Homme claimed the group was about reinventing the blues, the album is really a journey through open-ended, Black Sabbath-inspired jams and heavy psychedelia.

At a Vultures concert in Charlotte, North Carolina, Grohl plays roaring combinations and staggered, slashing beats, executed with his trademark massive sound and redwood-thick groove. The band's album only cements this sonic ID. The cacophonous tom overload of "Mind Eraser, No Chaser," the four-on-the-floor thump of "New Fang," the gluey groove goodness of "Scumbag Blues," the roly-poly rhythms of "Bandoliers," and the full-on Led Zeppelin ripping of "Reptiles" prove Grohl capable of launching a new era of air-drumming fanaticism.

Speaking by phone with Modern Drummer from Homme's Pink Duck Studios in Los Angeles, Grohl reveals the secrets to consistency and volume, praises the beauty of dance grooves, and explains the inner workings of his hot new band.

MD: Them Crooked Vultures really shows the reinvention of Dave Grohl the drummer. What inspired these new ways of expression?

Dave: I hadn't played drums seriously in a long time. I'd skipped in and out of studios with friends, but I hadn't been in a band as the drummer since Queens Of The Stone Age, which was eight years ago. So finally having more than a few hours to sit down behind the drumset, 1 started discovering things I was capable of doing that I'd just never had the opportunity do to before. It was almost like I'd been away from the instrument for so long that I came back to it with a totally new perspective.

MD: How did you put that perspective to use?

Dave: Rather than just sit down cold and play the same chops I'd always been playing, I sat down and got comfortable and got warm and started to reach out more than I ever have. It's rock 'n' roll-I'm not reinventing The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway. But still, there were grooves I had never played. And there were little tricks and flicks I did that I had never imagined before, because maybe the songs I'd been playing and recording had never required that.

Also, when I sit down to play with someone, whether it's live or in the studio, I usually adapt to what I consider is necessary. I don't sit down and "do my thing" when I jam with someone. I usually kind of feel it out and meet them halfway, extend my hand to the songwriter or whomever. I like to become whatever the music requires me to become. And in this case there were no boundaries. The three of us walked into the studio as multi-instrumentalists who had years of wonderful music behind us, and we didn't talk much about what we were going to do. We'd just do it. The idea was that it would sound like the three of us. So there weren't boundaries or restrictions or parameters; it was open season. I went berserk.

MD: You certainly went berserk creatively. There are so many trademark grooves. With Queens Of The Stone Age you created a classic beat on "No One Knows." There are a number of similar beats with Them Crooked Vultures.

MD: You certainly went berserk creatively. There are so many trademark grooves. With Queens Of The Stone Age you created a classic beat on "No One Knows." There are a number of similar beats with Them Crooked Vultures.

Dave: I don't pick up the sticks and jump on the tour bus for anybody. I might go play drums and record with friends. But when it comes to being in a band, 1 only truly want to play drums with Josh Homme. He is a brilliant musician, producer, and songwriter. He brings out the best in everyone. He surrounds himself with musicians who are willing to rise to the occasion or challenge themselves or do things they've never done before. And his riffs are so good. He's the only other person I've ever met who plays his guitar like a drumset.

MD: So you were copping his riffs for your patterns?

Dave: When Josh goes [sings riff from "No One Knows"] , I just do my version of what he's doing on guitar. If he goes [sings riff from Them Crooked Vultures' "No One Loves Me & Neither Do I"], I'm just mimicking his riff with my drums.

MD: And there are tracks where the groove is sucking all the air out of the room. Like on "Scumbag Blues," there's nothing between the instruments.

Dave: And you realize that I am playing with John Paul Jones! That has everything to do with why I played the way I did on the album. I am a Zeppelinologist. I grew up worshipping that band like they were my church. I didn't go to church-I listened to Led Zeppelin, and that was all I needed. They were God to me. I learned a lot about groove and drumming and feel from those albums. When I listened to those records I didn't want to know exactly how Bonham did what he did-I wanted to know why he did what he did.

MD: That's a great question.

Dave: Look, there are not many people who are capable of doing what John Bonham did. He's the greatest rock drummer of all time. It's true. The guy was so well balanced, he could do anything. And he was fearless. He wasn't perfect. But he was the most beautiful human rock drummer of all time. Anyway, it was his intention that fascinated me. Why did he do that particular thing there? Why is he so behind the beat on that part? Why did they keep that mis-hit in? His playing had such personality and had its own fingerprint, its own blueprint.

MD: So what did working with Bonham's closest musical partner bring out of you?

Dave: I know every riff that John has recorded on album, solo projects and otherwise. When we got into the music I thought, This will be easy. What, I'll be John Paul Jones' favorite drummer ever? No, I'll just relax and jam. I'd met him when he worked on a Foo Fighters record, and he and Jimmy Page jammed with us at Wembley Stadium a few years ago. We became friends. With Them Crooked Vultures, we started jamming, and within minutes I knew it was the best band I had ever been in. We were noodling, dude! And I also thought, Man, I am really killing it! The feel was good and the time was there, the pocket. Then I realized that was all John Paul Jones making me sound good.

MD: How did he do that?

Dave: That is what he does. He's had years of studio experience, playing charts, even long before Led Zeppelin. He has so much feel. He finds your groove and sticks to you like glue. So in "Scumbag Blues," that's Josh and John and me in a 10' by 10' room recording the song live.

MD: No clicks on the record?

Dave: There's a click on only one song, "Reptiles."

MD: Many of the songs comprise various sections. Did you record them in one pass or in parts?

Dave: Usually we would start the day by drinking fifteen pots of coffee. We'd sit on the porch, then it was like riff roulette. We'd say, "Who's got one today?" John might have one and we'd play along. If we felt we had the foundation of a song or at least a starting block, we'd go in and start jamming. By nine at night we would have turned a verse/chorus basic idea into an eight-and-a-half-minute epic instrumental. Then we would shave it down.

Once we had an arrangement we thought made sense and we could play it through, we'd take a break, set up the mics, and record it. Some are first takes, some are second or third takes. Then we did broad editing in Pro Tools. But it was like doing it to tape. We would mix and match verses or choruses, depending on the best version. And we were good about tempos, so we didn't need click tracks.

MD: So there are no grid maps.

Dave: Fuck, no.

MD: Your tech, Gersh, noted that when your drumming is up on the recording console, all the VU meters hit the same level because you strike everything with equal weight and intensity. That explains the power and meatiness of your groove.

Dave: Consistency is very important to me. Perfect time, perfect tempo, locked-in perfection doesn't turn me on. But consistency does. It can still be spontaneous and insane, but when I play drums in the studio I don't barrel down on my drums like I do at live gigs.

MD: Really? Your power is one of your trademarks.

Dave: I will pound the heck out of them for sure. But the live gig is a marathon. I really beat the crap out of my drums live. Not because I think it sounds great, but because I get so excited to play. In the studio I play the drums so that they'll sound good. If it sounds great to crack the snare, then I crack it, hard. If it chokes, then I back off.

A long time ago I learned a lesson with three microphones in my bathroom in Seattle. I had a Fostex cassette 8-track and a drumset, and I wanted to record some songs on my own. So I arranged my three mics: room mic, kick mic, and snare mic. I recorded a drum track and listened back and realized I was bashing my cymbals too hard. I couldn't really hear the snare. So I did another take and laid off the cymbals a little bit and gave it a little more snare. I did a roll, but I lost that because I didn't have mics on the toms. So next time I did the roll I laid into the toms more. Basically I learned to equalize or mix myself in the room.

As most drummers should know, you want the recording to sound great with one microphone in the room. I want to be able to put one beautiful Neumann mic fifteen feet away from the drums and make it sound like the greatest mix I've heard in my life. So you play to the room. Often that doesn't mean bashing your drums to shreds. I try to be a responsible drummer in the studio, be consistent, and play to the room so I can get a bigger sound by playing less.

MD: You recorded yourself and judged the results.

Dave: It's a common mistake: People imagine that the harder you hit the drums, the bigger they'll sound. A lot of times it's the opposite. When you're at the bar down the street and you have two microphones and you want to tear people's faces off, that's when you start to splinter sticks and break stuff.

MD: So you're not stomping quite as hard.

Dave: It depends. A good example is the second half of "No One Loves Me & Neither Do I." I'm practically busting through my kick head on that section because I want that wallop in the room. I'm not really going hard on the cymbals, though. Every song is different, it's just a matter of having that dynamic control over each one of your [sources], knowing what should be louder and when and what should sit back.

MD: When you're creating one of those memorable beats, is it something you think about away from the drumset, or is it the first thing you hear?

Dave: It's somewhere between being clever and being flashy, where you can find something that becomes a hook. I'm not a trained drummer, so I have bad habits. There are certain things I just can't do.

MD: But you've raised your bar with this band. You're playing bass drum/ tom combinations I've never heard from you.

Dave: Oh, thanks. I've always found simplicity to be a lot more entertaining than complexity. I like disco drumming. I like AC/DC. I like old rock 'n' roll. I like the Ramones. Drumming that's just so simple you almost don't even notice it. It's beautiful in its restraint and its minimalism. That's what I really dig.

It's like [Led Zeppelin's] "Kashmir." That song is so perfectly spare and sparse, until you get to the section with the kick drum flip. That's when you realize Bonham is a lot better than he's leading you to believe.

MD: Old video of Bonham shows he wasn't bashing all the time either. He was like a big-band drummer at times-he swings.

Dave: Honestly, it's a popular misconception that beating the crap out of your drums is the way to make them sound bigger. It can, but not all the time.

MD: Gersh also mentioned your sliding bass drum foot technique. You don't always play heel-up?

Dave: Me and Gersh, it's like The Newlywed Game! First of all, I sit low, so I can push forward with my foot and rock my foot back and forth a little bit when I need to do something that's quicker. When I'm doing faster footwork I rock my heel back so I can bounce my foot off the pedal. But I'm not heel-up all the time.

In some songs I let the beater rest on the head after I hit it, just to kill the resonance of the head. And there are other songs when I smack the crap out of the bass drum to get as much ring as I can out of it. I think I need a foot cam to really answer that one!

MD: You play a few odd-meter tracks on the album. Do you count, or do you approach the meter melodically with your guitarist hat on?

Dave: I'm thinking more in terms of melody and riff than numbers. I still get confused with time signatures. When people say it's in seven or nine or five, it doesn't really register with me as numbers. I use my ear. If it's way too complicated, then good luck!

Taylor Hawkins told me he once got a tip from Gary Novak that if a time signature is too complicated, just cut it in half and count those halves. But that's way too complicated for me. It would ruin my experience.

MD: Playing guitar for so many years must have changed your view toward drumming.

Dave: The two came hand in hand for me. I began learning guitar when I was eleven. But I had an understanding of the drums; I would play [Rush's] 2112 or punk rock records on my pillows. I didn't have a drumset, but I understood what the drummer was doing just by listening. Not that I could actually do it, but I got it. Since I was young I've been one of those guys who plays drums with his teeth while he walks down the street. I'm humming a riff and coming up with a drum line by grinding my teeth. You should interview my dentist!

MD: Did you create some Vultures parts away from the kit like that?

MD: Did you create some Vultures parts away from the kit like that?

Dave: Once the riffs started taking shape. I would really try to minimalize everything. It's not unlike writing a song. Writing a drum part for the song is just as important as writing the lyric or the chorus or the title. It's important that a drum track has structure and arrangement and that you're using your head; you're not just playing and bashing away and doing the same thing every time. It's important that you think about entering into a section and building the song and sitting with the bass. There are a lot of things to consider, but ultimately make it as simple and memorable as possible. Whether it's Tony Thompson or lohn Robinson, there are drummers who write parts, and it's not rocket science. They're just great drum hooks.

MD: Can you give me an example?

Dave: Take a song like "Dead End Friends." I got to the studio at midnight. And Josh had to leave in fifteen minutes. He played me a guitar riff and said, "Let's go." We did two takes in fifteen minutes, and the second take was the keeper. I'd never heard the song before. And I was kind of drunk. Then there are songs, like "Bandoliers," that I'm really proud of because of the groove and the composition that was put into that. And I recorded the whole drum track by myself when everybody was out screwing around. We'd been working on the arrangement all day, then Josh split and John went out to eat. "Where is everybody?" So I recorded the whole song by myself.

MD: "Elephants" is one of the dance grooves you talked about. Did you think differently regarding those songs?

Dave: We are probably more inclined to play dance grooves over rock songs than rock beats on rock songs. That's the way the three of us jam. We put a lot of emphasis on the groove and that it be somewhat danceable, whether it's "No One Loves Me," which swings, or "Dead End Friends," which has a cute go-go shape to it. Or "Gunman," which has a blatant disco beat, the one beat I promised myself I would never play.

MD: Are there things you do within the beat in the moment to make it groove more? Do you make adjustments?

Dave: Sure, I do that all the time, to sit comfortably in the groove. That's what I do. You have to pay attention to whether the song is grooving or not. It's hard for me to articulate a lot of what I do as a drummer, because I am not a technical musician. I'm a big dummy when it comes to anything technical or rudimental. So to me it's all about the feel. That's really hard to describe. I heard a producer trying to describe the formula that made up Bonham's behind-the-beat feel, which is ridiculous. It's just feel. You can't explain it; it is or it isn't. It's my mission to try to get drummers to stop listening to other drummers and listen to themselves.

MD: I've read that you don't practice away from the kit.

Dave: Playing by myself is a very lonely and depressing feeling. So I prefer to play drums when there's music happening at the same time. It's when I'm jamming that I get practice in.

MD: So you didn't feel any need to get your chops in shape after being away from the kit for so long?

Dave: Not really. The most important thing to me was that my body be able to do the things it used to do. If I can imagine doing it, I can probably pull it off. If I can hear it in my head, I can make my hands and feet do what they need to do. It's just a matter of being physically capable of pulling off the things I have in my head.

MD: The early press on Them Crooked Vultures reported the band was basically doing Zeppelin. Did you feel you were channeling Bonham at times?

Dave: There are sections that we stretch out into jams. They're totally open to anyone taking it and running with it. There are times where John leads the pack or Josh goes in his direction. It's those moments where I feel like what we're doing is not the same as what Led Zeppelin did, but we're doing it for the same reason. We just played at Royal Albert Hall, and that was an hour and fifty minutes long. Those jam sections are stretching out into eight or fourteen minutes. It's moments like that on stage where John and I are just looking into each other's eyes, building a jam from a whisper to a big crash.

MD: And that dance-groove mentality must be in there as well.

Dave: For sure. That's the fun that John and I have. While Josh and [Vultures touring guitarist] Alain Johannes are focused on their playing and their pedals and their vocals, John and I get to play with the groove. We try to make each other laugh by tossing little bits back and forth. The audience might not notice what we're doing, but we're getting away with murder back there.

MD: You used three drumsets on the album, as well as a toy set on "Interlude With Ludes."

Dave: That's was Josh's daughter's drumset. That's one of the great things about working with Josh. He'll say, "I want you to go in and play a random pattern using this block of wood and my kid's drumset." He records it with one microphone, and it's distorted as heck.

MD: The drumming on "Interlude With Ludes" almost sounds like a Stephen Perkins thing, with weird drums and editing. Is that live playing?

Dave: Just live, just me doing one pass. That's how much thought is put into a lot of this music. Very little. That's the instruction I would get from Josh: "Here, put that block of wood on a stand. Cool. And just do whatever, but don't play an actual beat."

MD: Did that ever make you nervous, like you needed more time to work out a part?

Dave: No. It's just a matter of what the song deserves. A song like that deserves something off the wall. A song like "No One Loves Me" deserves something that is heavy like a wrecking ball. You just have to figure out what it needs and do it quick. Don't spend too much time thinking about it.

MD: As a frontman and a drummer, have you noticed other drummers focusing on things that don't actually help their playing?

Dave: It depends what you're playing and why you're playing it. If you're playing on a song, then why not play for the song? If you're looking to jam, then just go. It's hard to say. I think feel and groove are overlooked a lot. Even something as simple as "Smells Like Teen Spirit" or "Heart-Shaped Box"-people wouldn't recognize those songs as songs that have groove, but they do in a way.

MD: But "Smells Like Teen Spirit" is one of the great rock drum moments.

Dave: Thank you.

MD: That's when everyone said, "Who is that guy?" The part is perfect for that song, and its energy is just impossible. And it has that massive drum sound.

Dave: I think one of the reasons the sound was bigger on "Smells Like Teen Spirit" was because I was doing less. There was that space between the beat; there was that air. When you chop it down to its bare essentials, that's when you can feel it, and you know more is less. That's when you know how to impress with less!

Words: Ken Micallef