Electronic Musician

THE FOO FIGHTERS TAKE A LOW-TECH APPROACH TO HIGH-INTENSITY ROCK

THE FOO FIGHTERS TAKE A LOW-TECH APPROACH TO HIGH-INTENSITY ROCK

"You know that scene in The Wall where the faceless people are falling into the machine that’s grinding them into paste?” asks Dave Grohl from his 606 Studio in Los Angeles. “Digital editing has robbed drummers of their identity, just like that. I’m heartbroken by what heavy-handed producers have done with drummers over the last 10 years.”

“A drummer walks into a studio,” he continues, like he’s telling a Borscht Belt joke. “He says, ‘This is how I play the drums,’ and the producer says, ‘That’s not good enough. I am going to make you sound like a machine.’ That’s fucking lame! I am not the greatest drummer in the world, but when I record drums, it doesn’t sound perfect and I am all over the place and the cymbals wash a little hard, but that’s how I play the drums. If you don’t like it, don’t call me back. I wish that every drummer would tell their producer, ‘That fucking machine doesn’t make me sound like me. It makes me sound like you, and you’re not the drummer, motherfucker.’ We’ve got Taylor Hawkins — who is the greatest fucking rock drummer I’ve ever played with — why not let Taylor sound like Taylor? So that’s why we used tape and no computers.”

“A drummer walks into a studio,” he continues, like he’s telling a Borscht Belt joke. “He says, ‘This is how I play the drums,’ and the producer says, ‘That’s not good enough. I am going to make you sound like a machine.’ That’s fucking lame! I am not the greatest drummer in the world, but when I record drums, it doesn’t sound perfect and I am all over the place and the cymbals wash a little hard, but that’s how I play the drums. If you don’t like it, don’t call me back. I wish that every drummer would tell their producer, ‘That fucking machine doesn’t make me sound like me. It makes me sound like you, and you’re not the drummer, motherfucker.’ We’ve got Taylor Hawkins — who is the greatest fucking rock drummer I’ve ever played with — why not let Taylor sound like Taylor? So that’s why we used tape and no computers.”

Wasting Light, the Foo Fighters’ seventh album, is a messy, often distorted, over-the-top record that pulses with attitude and energy. Every Foo Fighter’s album is an adrenaline junkie’s dream, the twin powers of Dave Grohl and Taylor Hawkins guaranteeing maximum energy like twin turbojets propelling a 747. But Wasting Light, recorded analog to tape (API 1608 32-track, two Studer 827s) with no computers, not even to mix or master, is an entirely different beast. You hear guitars clipping, cymbals pushing VU meters into the red, the sound of a live performance: blood, sweat, and tears (literally). What you don’t hear is a grid. Or Autotune. Or perfectly lined-up drums.

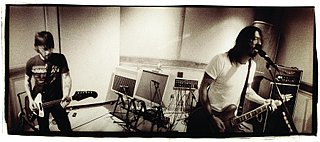

Deciding to track at Dave Grohl’s house with producer Butch Vig and engineer James Brown (veteran producer/engineer Alan Moulder came in to mix), the band (Grohl, Hawkins, Pat Smear, Nate Mendel, and Chris “Shifty” Shiflett, and bassist Krist Novoselic on one track) set up in the garage (drums), the living room (control/live room), and in closets (vocals), with no sound treatment and plenty of bleed. Three baffles were placed behind Hawkins’ vintage Ludwig drums, but that was it.

“I am no stranger to tape,” Grohl says. “Call me dumb, but the simple signal path of a microphone to a tape machine makes perfect sense to me. There’s not too many options, and the performance is what matters most.”

But not everyone agreed with Grohl’s “analog only” rule. “The first song we recorded, we get a drum take and Butch starts razor-splicing edits to tape,” Grohl recalls. “We rewind the tape and it starts shedding oxide. Butch says, ‘We should back everything up to digital.’ I start screaming: ‘If I see one fucking computer hooked up to a piece of gear, you’re fucking fired! We’re making the record the way we want to make it, and if you can’t do it, then fuck you!’ Nobody makes us do what we don’t want to do. ‘What if something happens to the tape?’ ‘What did we do in 1991, Butch?’ You play it again! God forbid you have to play your song one more time.”

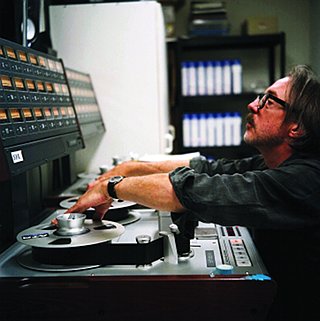

With that behind them, the team settled into the tracking process: Hawkins recording drums to click, and Grohl’s scratch guitar and scratch vocal to a master reel, which was the reel used for edits. Rather than recording numerous drum takes, punch-ins and edited transitions completed the master takes. The master reel and a blank slave reel were striped with SMPTE timecode: “We would lock those two striped reels together and simultaneously bounce down the drums to four tracks (kick, snare, and a stereo mix of all the other drum tracks); Dave’s scratch parts would also get bounced over,” says Brown. “We would then record all of the overdubs to the slave reel. We never went back to the master reels, due to the fact that we ended up mixing back up at the house...under normal circumstances, one would lock the master back up with the slave and use the first-generation drum tracks from the master reel (in other words, not the bounced-down drums on the slave reel) when mixing . . . however, with only 32 channels on the console, that wasn’t an option for us. All of the mixes, with the exception of ‘Dear Rosemary,’ were mixed using the bounced-down drums.” Everything was mixed with all eight hands (Grohl, Vig, Brown, and mix engineer Alan Moulder) on deck, riding faders in real time to tape.

“In Pro Tools, you can take a band that’s not very good and make them razor-tight,” Butch Vig explains from Silverlake, California, where he is working on the forthcoming Garbage album. “But this became more about the band’s performances, about what they would have to do in order to make a great record. They wanted a challenge. That was exciting. Somebody would want to do a punch, and I’d say, ‘If you go over it, it’s gone.’ The Foos rehearsed very hard to pull this off, and not many bands could do it.”

Vig and the Foos did allow a click track for drums; they’re not insane. But even then, Vig discovered the joys of free flying and forgetting the grid.

“Clicks were used, but it’s loose,” Vig says. “Sometimes we’d worry about the timing or a snare hit. Then we realized that when everything is off just a few milliseconds, the sound gets wider and thicker. If you zoom in with Pro Tools and put everything exactly on that microscopic downbeat, it’s so perfect that it loses a thickness. If everything is off just a little bit, the music just gets wider and thicker.

“Clicks were used, but it’s loose,” Vig says. “Sometimes we’d worry about the timing or a snare hit. Then we realized that when everything is off just a few milliseconds, the sound gets wider and thicker. If you zoom in with Pro Tools and put everything exactly on that microscopic downbeat, it’s so perfect that it loses a thickness. If everything is off just a little bit, the music just gets wider and thicker.

“It all made our brains switch into a different focus,” he adds. “For one thing, everyone is used to looking at a computer screen, so you look at the music, what the timing is, what the waves are like. There was no computer screen at Dave’s, so I would look at the meters, which is how I initially learned how to record. We set up this huge HD monitor on the meter bridge of the tape machine so we could see how hard we were hitting the tape. Eventually we started feeding that live to the Net, with no explanation!”

BUNKER DRUMS

Down in the concrete bunker/basement that functioned as a drum booth, engineer James Brown had his work cut out for him. Brown used the same close mics as he would for any date: Yamaha SKRM100 Subkick (with custom API pre) and an AKG D112 (custom API pre/Inward Connections EQP2/Distressor) on kick; Shure SM57 on snare top and bottom (custom API pre/EQ’d and summed in API 1608/Distressor); AKG 452 (Neve 1073) on hi-hat; Josephson E22S (API 1608 pre) on toms; AKG 452 (Neve 1073) on ride.

But as the concrete floor created mad reflections, Brown experimented with overhead and ambient placement. Grohl demanded more “garage” whenever things became too tidy-sounding, which meant turning up the room mics, and turning down the close mics. For overheads, after a shootout, Brown settled on a Violet Designs Stereo Flamingo (Neve 1073) and Shure SM58 “trash” (custom API/Urei 1176 (all buttons in, “Brit mode”). Kit ambience (about four feet out) was a Neumann M49 (Great River/Harrison 32EQ/Retro Instruments Sta-Level); overhead ambience was a Violet Black Finger (Neve 1073/Urei 1176); main ambience, two Soundelux 251s at knee level against the garage door (custom API pres/Dramastic Audio Obsidian). For floor ambience, a pair of Crown PZMs (custom API pres/DBX 160).

“I’d use the same mic placement in that garage, regardless of the mics,” Brown explains. “Turning the Soundeluxes away from the drums and pointing them into a corner tempered the top end. The mic choices were more about choosing cymbals and asking Taylor not to hit so hard. That allows more room for the snare and kick to cut through in the ambient mics. That’s when you can really hear the garage; the air isn’t getting sucked up by cymbals and midrange.”

Room mics were placed eight feet out from the kit—basically, against the garage door at the farthest point away from the drums. “It was purely to temper the cymbals,” Brown says. “The garage being untreated and literally a concrete box, it was a very harsh, loud environment. So it required an unconventional miking setup. The Crown PZM, whatever you stick it to, it expands its pickup area, so those added a lot of punch in the low/mid area. The Shure 58, I stick it directly behind the drummer’s head and compress the living daylights out of it with all the buttons in on the Urei; that adds a trashiness to everything. The Neumann between the garage door closer to the drums is to capture some of the air around the kick drum. There are three mics on kick drum: one inside, aimed at the beater; then the NS10 sub bass; and the kit ambience from the Neumann. The mic pre choices are what I generally use. For tom, kick, and snare, I used my go-to choices.”

Grohl sang through his time-tested Bock 251 (Neve 1073/Distressor); Brown used his go-to mics for bass and guitar. Bass choices were an Avalon U5 DI (Neve 1073/Inward Connection EQP2/Distressor) and two close mics on Nate’s Ashdown ABM 900 EVO/Ashdown 8X10 cab: Lauten Clarion (FET) and a BLUE Mouse. Guitar mics were many: two RCA BX5s, Royer R121, Josephson E22S, Shure SM57, Shure SM7, Sennheiser 421. Guitar pres were “almost exclusively Shadow Hills Quad Gama—occasionally, I would use the API board pres,” says Brown. “That would in turn be fed through a Universal Audio LA3A limiter, just touching the peaks. Nearly everything went through a fader and EQ on the API 1608 console that Butch would manipulate during performance to send as clean a signal to tape. We had to tape a guitar pick to the fader track to stop him burning a hole in the tape!”

After tracking instruments, Grohl cut vocals, typically sitting next to Vig and Brown in the makeshift control room. As with everything he does, Grohl pushed himself to the max.

“Ask Dr. Phil about my headaches!” Grohl laughs. “I like to make vocals feel atmospheric and ethereal. But then I want them to sound like I’m in primal scream therapy. Some things I am singing I can’t make sound pretty. Punk rock is my identity. I am from a little town in Virginia, a high school dropout who wanted to play punk rock. So when I am screaming my balls off, it’s because I don’t feel any different than when I was 15.

“Anyway, I do get headaches. I want a song to have maximum emotional potential when I am singing in the studio. When the mic is picking up every tiny inconsistency, you really strain to make it sound right. And I sit down to sing. That’s the only way I know how to do it. Maybe I feel funny ’cause I don’t have a guitar on. I project the same; I don’t know how else to do it.”

“Anyway, I do get headaches. I want a song to have maximum emotional potential when I am singing in the studio. When the mic is picking up every tiny inconsistency, you really strain to make it sound right. And I sit down to sing. That’s the only way I know how to do it. Maybe I feel funny ’cause I don’t have a guitar on. I project the same; I don’t know how else to do it.”

RETROSPECTION, INTROSPECTION

“We did a couple songs where Dave sang right next to me,” Vig says, “like, ‘I Should Have Known.’ Lyrically, there are references to Kurt Cobain, but I don’t know if Dave would admit to that. We ran Dave’s mic into a Space Echo there—it’s got this spooky, distorted sound. At the end of that take, the hair on my neck stood up; I couldn’t say anything. Dave looked like he was crying, ’cause he was singing so hard. He was obviously channeling something inside. It’s one of my favorite songs on the album, and the darkest and weirdest, in a way. I love that song.”

Grohl won’t confirm that “I Should Have Known” is about Kurt Cobain—only that the doomed legend is in there, somewhere. “There is something to be said for starting over,” Grohl says. “To be able to say, if this all ended now, I’d be totally okay with it, and I’d start over again. ’Cause that’s what I’ve always done. I’ve always felt like this is temporary, ever since Nirvana became popular. So a song like ‘I Should Have Known’ is about all the people I’ve lost, not just Kurt.

“There was a lot of retrospection and introspection going back to the way we used to make records,” he continues. “and with someone who started my career 20 years ago: Butch. I wouldn’t be doing this if not for Butch Vig. After we were finished, I realized there’s a reason why we’re here, and why we made the album the way we did, and why we used Butch, and a reason why Krist Novoselic played on a song. I was writing about time. And how much has passed and feeling born again, feeling like a survivor, thinking about mortality and death and life, and how beautiful it is to be surrounded by friends and family and making music.”

Ultimately, Wasting Light is a life-affirming, uplifting record, like most Foo Fighters records — from the roaring opener, “Bridge Burning,” and the guitar shrapnel counterpoint of “Rope,” to the Ministry-esque death-metal howl of “White Limo” and the introspective “I Should Have Known.” Somewhere in his 40s, Dave Grohl comes to grips with his past by facing his present.

“This band was a fucking fluke,” Grohl says. “To think now that we can headline these huge shows and there are these huge expectations, like, ‘You better make a fucking hit record!’ That kind of shit. So, okay, I’ll go back to my garage, ’cause that’s what everyone thought we shouldn’t do. It diffused any of that expectation. If we have songs that mean something, and you hear them once and they stick, and they’re recorded so it sounds like a beautiful explosion and it feels like human beings making music, then we’ve accomplished everything that we’ve wanted to do. It made perfect sense. Why do it the way everybody else does it? I want to sound like us, like the Foo Fighters.”

BIG SOUND ON A SMALL BUDGET

BIG SOUND ON A SMALL BUDGET

Engineer James Brown’s Advice for Getting Past Gear Limitations

“If you only have cheap mics and pres on hand, it doesn’t mean you can’t get good sounds,” Brown says. “Understanding mic placement can be the difference between your work sounding like it’s made up of a bunch of disparate sounds, as opposed to a cohesive, robust-sounding recording. The main rule of thumb is, if it sounds good in the room, there’s a good chance it will sound good recorded. Then if you can add to that an understanding of phase cancellation and how to avoid it, you’ll be on your way. The rest of it is all about the way you hear things. But it’s hugely important to nurture an understanding or feel for how musical parts and sounds interact and fit together—the alchemy of it, if you will. There’s an art to engineering music, so at some point you have to let go of all of that knowledge and start thinking about it in those terms.”

DAVE GROHL

On tape…

We’ve made many Foo Fighters to 24-track tape. I am no stranger to tape. I’ve always found it much easier. Call me dumb, but the simple signal path of a microphone to a tape machine makes perfect sense to me. There’s not too many options and the performance is what matters most.

On the way “I Should Have Known” swings like a beast…

It’s funny you say that, because that song happened half way through preproduction. We didn’t enter into the recording with that song. I just did that in my bedroom. I sang it and played the riff. And everyone wanted to work on it. The first time we played it, the hairs on the back of necks were standing on end. Then we went home and thought about it, and the next time we played it, it sounded like shit. It had none of the passion or the energy or the combustion of the first take. We suffocated it. I hated it. I didn’t want to think about the piece of shit. We ruined it; we’re fucked. Half way though we tried it one more time, and we tried to clean it up, spent a week on it. I still hated it. It sounded like some bad Coldplay B side. Fuck this! Why can’t it be chaotic and out of control and why can’t we let it explode? Don’t try to rein it in. Let it go free, I said. I told Taylor to go bananas and then that was it. You have to accept those moments and let it be. I wouldn’t want to take my children and turn them into something they aren’t, and it’s the same way for music.

On abandoning computers…

Nobody makes us do what we don’t want to do. Nobody ever has, and nobody ever will. If it was here at 606 or Ocean Way or Electric Lady, if I saw a computer hooked up to a piece of gear, I would have been hightailing it out the door. Fuck you and fuck you. Cause you don’t have to. What if something happens to the tape? You fucking do it again! What did we used to fucking do? What did we do in 1991, Butch? Something happens to the tape, oh well, you have to play it again. God forbid you have to play your song one more time.

On recording in his garage:

If this band that has walked these steps for 16 years and has managed to survive, good and bad things to where we’re playing stadiums—that wasn’t even in the cards. We didn’t mean to take over the world. This band was a fucking fluke. To think now that we can headline these huge shows and there are these huge expectations, you better make a fucking hit record! That kind of shit. Okay, so I will go back to my garage, cause that’s what everyone thought we shouldn’t do. It diffused any of that expectation. I’ve been in a six million dollar drums rooms that sound like shit. But demos in my garage with a shitty drum set sound like a Jesus Lizard record. Pretty fucking good!

EM: Is it about capturing feel and truth?

It has to have energy and personality. Character, and it has to feel…all my favorite records and musicians and drummers…imagine Pro Tooling Jimmy Page with Zeppelin? Imagine slamming Keith Moon’s drumming into the computer? If we have songs that mean something and you hear them once and they stick and they’re recorded so it sounds like a beautiful explosion and it feels like human beings making music, then we’ve accomplished everything we’ve wanted to do. And that was it. It made perfect sense. Why do it the way everybody else does it? I want to sound like us.

On cutting vocals and headaches…

I am good to go from the first take. I do it a couple times. I was sitting in front of the board with headphones with Butch and James. Handheld the mic. Taylor just heard me scream my balls off. He was worried! He was afraid for my voice. I do get headaches, but I don’t know why. When you play live, you settle into some method of doing it without hurting yourself. I want a song to have maximum emotional potential when I am singing in the studio. When the mic is picking up every tiny inconsistency, you really strain to make it sound right. I am not a singer; I don’t know what I am doing.

EM: So you began at 606, then to the garage?

EM: So you began at 606, then to the garage?

We spent three weeks in preproduction at 606. I thought the more prepared we are when we get to the house the less we have to worry about the songs and the more we can focus on the sound. Having never made a record in the garage, nobody knew what was going to happen. We had the house wired and the gear ready, but that doesn’t make a great record, people do. I wanted to make sure the songs were ready so we rehearsed every day, eight hours a day. Just to the point where there was still some mystery to them. But the process inspired the lyrics. There was a lot of retrospection and introspection and nostalgia going back to the way we used to make records. And with someone who started my career 20 years ago: Butch. I wouldn’t be doing this if not for Butch Vig.

On the process:

Butch likes to do one song at a time. So we would start on Monday with drums, and have a rhythm track down with me and Taylor. We made sure we grooved. Then the next day would be bass, then the next day, Pat or Krist, then by end of the week we’d have an instrumental ready for vocals. Old school comping, four takes down to two track, one for a single, another for a double, then we’d load up harmonies, and go to a B reel, and make a slave. I was writing one song at a time. I had some idea of what to convey or sing, but each week I was working on lyrics. I am surrounded by my family, making a record in my garage, when we we’re finished, we weren’t writing 2112, it was what was on my mind each week. After we were finished, I realized that the album is about the album. There’s a reason why we’re here, and why we made the album the way we did, and why we used Butch and a reason why Krist Novoselic came down and played on a song. I was writing about time. And how much has passed and feeling born again, feeling like a survivor, or about mortality and thinking about death and life and how beautiful it is to be surrounded by friends and family and making music.

BUTCH VIG

On the garage…

I was initially dubious to do this record in Dave’s garage. I said, you have a million-dollar studio near your house, but he said, “I am not looking for a perfect sound, I am looking for a vibe.” A vibe and a sound. So we did it in his garage.

EM: You were in a garage, tracking to tape, no Pro Tools…

EM: You were in a garage, tracking to tape, no Pro Tools…

First, Dave said, “I want to do it in my garage.” Then he dropped the bombshell: “I don’t want to use any computers. No Pro Tools. All tape.” I said “okay, cool,” assuming that we’d record to tape then dump it into Pro Tools. But he was like, “you don’t understand, I want to record, mix, and master off tape.” It took me a second; that’s how I learned to make records, but I haven’t done that process in 15 years. Okay…you guys have to be able to play it really, really well. That is the bottom line, it’s about performances. We can fix everything in Pro Tools, you can take a band that’s not very good and make them razor tight and fix all the pitch and cut the songs up – I love Pro Tools. It’s an amazing tool. But this became more about the band’s performances that they would have to do, in order to make a great record. I think they’d gotten set in their ways that it was easy to go into a studio with Pro Tools; it’s not challenging. But they were up for the challenge. That was exciting. Every day was by the seat of our pants. Somebody would want to do a punch, and I’d say, “if you go over it, it’s gone. There’s no playlist, like in Pro Tools.”

EM: Were they all live takes with no punch in?

No, we punched in. But if there was a solo or section or chorus, they go for live takes when we would go back and fix things. But we didn’t meticulously overdub four bars at a time. Some things are live takes, live complete drum and Dave guitar takes. And a few of Dave’s vocals are one take all the way through. They really knew they had to go at the top of their game. The first couple tracks we did…we’d usually set up in play live, and we’d ultimately…I’d focus on Dave’s rhythm guitar and Taylor. They’re the glue. Often after a couple takes, say, “Rosemary,” they went back and we would do once we had the take, then I would say okay, cool, now let’s punch in a drum fill, and punch in, rewind, it was nerve-wracking. We’d clip off a snare, or you could hear the punch. We’d do it again. And Taylor could hear it, so we’d do it again. They understood that. Initially on a couple songs, I did old-school razor blade edits. Rosemary is one. It had a lot of edits. Then we realized that drum editing is very time consuming, it’s a better way to go, I would love the verse on one take, the chorus on another take, or a fill. There’d be ten edits in a song. All tape edits, just cutting the two inch tape. It takes a couple times. But after a couple songs we said f**k it, this is too time consuming. So we started punching in little things. Arm the machine and punch in the take til we got one we were happy with and one where you didn’t hear the drop out. I can still hear a bad punch out after the first chorus in White Limo. There’s a chunk drop thing in the drums.

EM: Did you use a click track?

Clicks were used but it’s loose, they move around, we wanted it to groove. A conscious effort to not worry about that. I am so used to making it perfect if you want. We all had to ease up on our criticisms. Sometimes your radar makes you worry about the timing or a snare hit, then we realized that when everything is off just a few milliseconds the sound gets wider. It gets thicker. If you zoom in with Pro Tools and put everything exactly on that microscopic downbeat it’s so perfect that it loses a thickness. If everything is off just a little bit the music just gets wider and thicker.

EM: Did you enjoy, and would you recommend the process?

It was exciting and made our brains switch into a different focus. A different headspace, and that was cool. It was a challenge then we realized it was a different vibe. I really had to force my brain to fire different synapses. For one thing, everyone is used to looking at a computer screen, so you can look at the music, what the timing is, what the waves are like. There was no computer screen so I would look at the meters, which is how I initially learned how to record. If you see the pics, tape machine down in the garage, we ran cables into the garage, and the control room over the garage, there’s a huge HD 64 inch monitor. That was on the tape machine, so we could see the VU meter bridge on the tape machine so we could see how hard we were hitting the tape. Eventually we started feeding that live to the net, with no explanation.

On recording drums:

We found right away that we had to pick the right drums. Some drums collapsed in there. Some overexcited the room. And the cymbals, because the room was so bright. Some kits sounded terrible in there. We tuned the drums to the room so they had a good midtone. There wasn’t any super low bass to the garage sound. You can hear that on the record, it’s punchy. Dave kept saying “more garage.” We had a couple faders on the API on just the room mics that we labeled garage. So we’d bring up the room mics when he said that. With only the dry mics it sounded like it could be anywhere. As soon as we brought up the room mics, that‘s the punchy sound of the garage. And the drum sound has a lot to do with the sound of the record. More ambient and room….as simple as that. The ambient mics were only 8 feet away, as close to the door as possible. Just a tight, punchy sound.

EM: Tell me about the knee-level room mics.

That gave us different midrange tones. Depending on the mic and its placement in the room. Some had more bottom, some had more upper, 1 or 2 k tones. We recorded the basics on an A reel, James allocated 12 tracks for drums. Then we made a B reel to finish the overdub sounds. And we mixed the drums to kick one channel, snare one channel, and all the other drums to stereo.

On mixing:

On mixing:

We went to Chalice to mix with Alan Moulder, locked the drums, 48 tracks, we did a few songs, but Dave wasn’t feeling it; “doesn’t sound like the garage anymore,” he said. So we decided to go back to the garage and mix manually, with no automation; the room we recorded in had no acoustic baffle or treatment. The drum room and the garage, and the control room, the room over the garage was terrible, really alive, super boomy, hard to tell what the low end was like…I was over the garage; I could hear Taylor, so we had bleed through the floors. Guerilla style!

We mixed manually on the API board, with me, James, Alan Moulder and Dave, all eight hands on board, all doing the faders, no automation; we couldn’t even do mutes. So every mix was a performance. Much like the recording was. I would do the vocal rides, Alan would man everything and effects, James would do the guitar, Dave would run the drums, but the drums were only four tracks and it was second generation. We didn’t go back, we didn’t have the inputs on the API to go back and lock up the A reel. So all the drums are second-generation mixed to the B reel. I would focus on the vocals, and I’d get it done, and everybody would say, “did you nail it? Did you miss anything?” We all started sweating. We’d jump up when we got a mix. It was so exciting, and so different from how records are made these days.

EM: Why did they take this approach?

Dave felt like he wanted to back and experience how he made his first couple records, which were much more raw. And by the seat of your pants. He has an amazing studio, but he wanted to go for a vibe and a sound and a performance, and not worry about making a perfect sounding album. That’s what we set out to do and that’s what we accomplished. The record sounds great but it doesn’t sound like a lot of the records you hear on KROQ. It’s rough and scrappy and fuzzy and over-distorted in spots. But that’s because we hit the API too hard when we mixed it. That’s okay, it’s exciting ,and it makes us feel good. I don’t know that a lot of bands will want to do this, because it’s a pain in the ass!

EM: Do you have any advice for trying this at home?

Look at the room you’re recording in and the gear you have and figure out a way to make that sound good. Don’t sit and pine that you need some Telefunkens, use what you have and figure out a way to make it sound good and then, concentrate on getting great performances. You have to be patient and get focused. Sometimes, with the Foos, they rehearsed a lot. Early in the year, we worked on demos, so he could figure out his angle, then they rehearsed their asses off. Then I worked with the band for three weeks, distilling the arrangements down. And working out the finessing the parts. You need a band that can play great, and is willing to do that. It’s so easy to manipulate stuff with computers. I don’t know if I will do this in the future. They have to be as good as the Foo Fighters, and can play that well.

Words: Ken Micallef