Dave Grohl has many great memories of Lemmy, but there’s one in particular that’s imprinted on his brain.

It was late morning in Los Angeles years ago, and the Foo Fighters frontman was en route to The Rainbow, Lemmy’s Sunset Strip hangout of choice, for an early-doors meeting with the Motörhead mainman. Halfway there, Grohl got a call: could he come to Lemmy’s apartment instead? Sure, said Grohl. After all, he’d never been through those hallowed portals.

“So I got to the apartment,” says Grohl, laughing, “and I was shocked at how fucking disgusting it was. These aisles of magazines and VHS tapes stacked three to four feet high, Lemmy sitting on the couch, in his black bikini underwear with a spiderweb on them, after just dyeing his hair black, doing a phone interview, with a videogame on pause on the television.”

Lemmy beckoned for Grohl to take a seat on the sofa next to him as he finished the interview. When it was done, Lemmy asked him if he wanted a drink. “It was fucking eleven-fifteen in the morning,” says Grohl. “I said: ‘Sure.’”

And there Grohl sat for the next five hours, on Lemmy’s couch, knocking back Lemmy-sized measures of Jack Daniel’s, with Lemmy in his underpants next to him. They listened to old Dudley Moore tapes and the new Motörhead album, during which the man who wrote and sang it stared into Grohl’s eyes and mouthed every lyric as it came through the television speakers. For a bourbon-fuelled Motörhead fan, this was as good as it gets.

“I will never, ever forget every little detail of that day,” Grohl says now. “Especially not the black underwear with a spiderweb and a black widow spider right where the dick is.”

Jack Daniel’s, Motörhead, spiderweb underpants, it’s a very Lemmy story. But it’s a very Dave Grohl story too. He may lead one of the most successful rock’n’roll bands of the past 25 years, but there’ll always be part of him that will forever be that teenage rock’n’roll fan. For all the record sales, the stadium gigs and the A-list names in his phone – and there are a lot of those – Dave Grohl is still one of us.

It’s 5pm in the UK and 9am in LA when he calls me via Zoom. He’s at home, dressed in sweatpants and a T-shirt and nursing a coffee. He’s already sorted out breakfast. “I know what it feels like to jump up in front of eighty thousand people and go: ‘Come on, motherfuckers!’” he says. “But I also know what it’s like to hear my alarm and go downstairs and make scrambled eggs and bacon for my kids.”

We ’re here to talk about the Foo Fighters’ yet-tobe-released tenth album, Medicine At Midnight, (rescheduled for February), and how a livewire punk-rock kid from Virginia ended up becoming a rubber-stamped stadium-straddling superstar. But mostly we’re here talk about rock’n’roll.

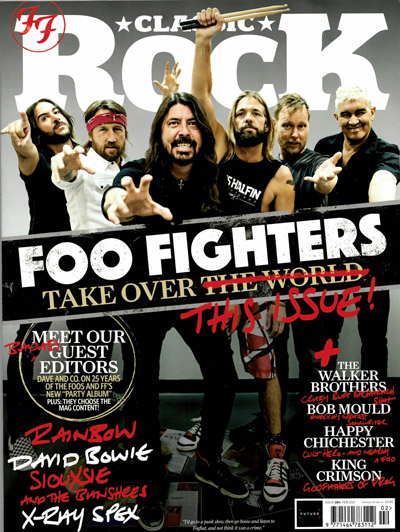

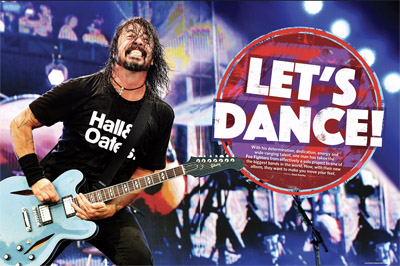

“Well,” Grohl says decisively, “I’m your man for that.” 2020 should have been a banner year for the Foo Fighters. As well as the intended release of the new album, it also marked the 25th anniversary of both their self titled debut and the formation of the Foos as an actual band, as opposed to a one-man project in which Dave Grohl played everything including the kitchen sink. “Oh god, man, we had a world domination scheme that lasted for eighteen months,” he says of the band’s pre-covid plans. “It had movies and documentaries and special gigs, and then that all kind of disappeared. We hit pause on everything in March and we all kind of retreated and went our different ways. I had a break for the first time in ten years, which was the most unusual feeling.” Six months after it was originally due to be released, Medicine At Midnight is headbutting the cage door, clamouring to be let out. It was recorded in a fast and furious few weeks at the end of 2019, in a big old rented house in Encino, California. Strange things happened there. More than one member of the Foo Fighters thought the property was haunted. “Oh, weird shit definitely happened,” says Grohl, although he won’t be drawn any further than that. Most of Foo Fighters’ recent albums have had an angle. There’s been the half electric/half-acoustic double album (2005’s In Your Honor), the back-to-basics garage record (2011’s excellent Wasting Light), the record of the documentary (2015’s star-studded Sonic Highways), the ‘Slayer meets the Beach Boys’ mashup record (2017’s Concrete And Gold). And Medicine At Midnight? If Grohl is to be believed, this is the Foo Fighters’ party record. “I thought rather than overcomplicate things and try to make this riffy prog rock record, which is a type of music we love, let’s simplify everything and make the choruses bigger and the grooves fatter and the tempos more up, so people will bounce around for three hours when we eventually get to play it live,” he explains. “You know when your parents start getting older and wearing things that they shouldn’t wear in public? That might be what the Foo Fighters are doing right now.” He uses the word ‘disco’ to describe the ninetrack album, and that snappy summary broadly fits songs such as quirky lead-off single Shame, Shame, with its snapping drum loops, and the defiantly funky title track. But it’s less John Travolta-in-awhite-suit, more The Game-era Queen or early-80s Bowie. “Most Bowie purists would tear me to fucking shreds for saying Let’s Dance is my favourite Bowie record,” he says. “But honestly, as a drummer listening to Omar Hakim and Tony Thompson [both of whom played on Let’s Dance], I’m, like: ‘Wow, they really incorporated this heavy funk into a lot of their songs.’ Those songs were danceable. I wanted to make a Foo Fighters album people could dance to.” Still, Medicine At Midnight doesn’t spend too much time showing off its Tony Manero moves before reverting to type. The speedy No Son Of Mine nods back to Grohl’s punk roots, while Waiting On A War and blockbusting closer Love Dies Young are arena-ready anthems that share DNA with past Foos megahits The One and All My Life. It’s a livewire record, and a joyous one.

“I mean, come on, that’s what we need at the moment, right?” he says. And it’s difficult to argue with him.

Dave Grohl grew up in Springfield, Virginia, a short drive away from Washington DC. The US capital was a hothouse for the early-80s punk and hardcore scene, and the teenage Grohl threw himself into it as both a fan and a musician. He felt at home there, surrounded by two or three hundred other misfits in the moshpit of some DC sweatbox or maybe playing on stage with his early band Scream. But while he embraced punk rock, he didn’t commit to some of its more exclusionist dogma.

“In the punk scene, there was this anti-hero, fuck-classic-rock’n’roll mentality,” he says. “And I understood, culturally and politically, why a lot of those punk-rock musicians disagreed with all that stuff. But at the same time I loved The Beatles and AC/DC. That music had my heart too. I’d go to this sweaty punk rock show, and then I would go home and listen to fucking Foghat, and not think it was a crime. [Mock-huffily] ‘I think I’m allowed to do both.’”

Still, he carried that punk-rock spirit with him when he schlepped up to Seattle in 1989 to join a second-tier grunge band called Nirvana. Nobody, least of all Dave Grohl, expected them to become the defining rock band of the 90s.

“When I first joined the band it was so much fun,” he says. “I lived on the couch in Kurt’s living room, we rehearsed in a barn, we set up our gear and played those songs and people bounced around and got hot and sweaty. I really loved the connection and the appreciation that Nirvana’s audience had with the band.

“And then there was a period where we started to feel a bit out of place, as the band got bigger and bigger, as we’re on television shows and pop radio and magazine covers. It felt a little uncomfortable. But I was also the drummer, so I wasn’t the most recognisable person in the band. I could walk in the front door of a Nirvana show and fucking nobody would really hassle me.”

I’m sure that’s not true.

“It’s almost true. My existence in that band was so purely simple. And then things got complicated and much darker. A lot of it had to do with drugs, a lot of it had to do with finally getting to a place that felt completely foreign and not entirely healthy. And over time that proved to be hard to escape from. So yes, there were a lot of really beautiful moments and a lot of really devastating moments. It ran the gamut.”

Kurt Cobain’s suicide in 1994 and the end of Nirvana is well-documented. Since then Grohl has largely steered away from covering his former band’s songs. On the handful of occasions that he has, it’s always been alongside Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic and latter-day touring guitarist Pat Smear rather than with the Foo Fighters. Tellingly, Grohl has never sung any of Cobain’s songs himself, instead preferring to enlist guest vocalists such as Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, Annie Clark of St Vincent, and Joan Jett.

“I wouldn’t feel comfortable singing a song that Kurt sang,” he says. “I feel perfectly at home playing those songs on the drums. And I love playing them with Krist and Pat and another vocalist. I still have dreams that we’re in Nirvana, that we’re still a band. I still dream there’s an empty arena waiting for us to play. But I don’t sit down at home and run through Smells Like Teen Spirit by myself. It’s just a reminder that the person who is responsible for those beautiful songs is no longer with us. It’s bittersweet.”

One of the many Foos-related projects that has been sidelined temporarily by the pandemic is a documentary film Grohl has been working on. Titled What Drives Us, it’s a hymn to the touring life and the romance of rock’n’roll that fuels every band at the very start of their career. As Grohl puts it: “It’s about what makes people throw their lives away and jump in an old van with their buddies and no guarantees that there’ll ever be any reward other than just playing music with your friends.”

Grohl interviewed several of his friends and peers for the film: members of Metallica, Guns N’ Roses, AC/DC, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, U2, Black Flag o does “Everybody had the same story,” he says. “Nobody ever thought: ‘I’m gonna take over the world and become a stadium-class rock icon.’ They were just like: ‘Fuck school, I’m getting in a shitty van with my friends.’ All of them, every single fucking one of them.”

Grohl has ‘got in the van’ twice in his career. The first time was in the 80s, a period that began with his stint as the drummer with Scream and ended with the point Nirvana suddenly went supernova. And then, for some weird reason, he did it again when he was getting the Foo Fighters off the ground.

The start of the Foos has been written about almost as much as the end of his previous group: how, in the aftermath of Kurt Cobain’s death, he recorded a bunch of songs he’d been writing during his time in Nirvana; how those songs became a debut album that was part cathartic exercise, part emotional life raft; how he brought in Pat Smear, Nirvana’s touring guitarist and co-founder of original LA punk rockers The Germs, along with bassist Nate Mendel and drummer William Goldsmith (long-since replaced by Taylor Hawkins) to turn this literal solo project into a band.

Still, Medicine At Midnight doesn’t spend too much time showing off its Tony Manero moves before reverting to type. The speedy No Son Of Mine nods back to Grohl’s punk roots, while Waiting On A War and blockbusting closer Love Dies Young are arena-ready anthems that share DNA with past Foos megahits The One and All My Life. It’s a livewire record, and a joyous one.

“I mean, come on, that’s what we need at the moment, right?” he says. And it’s difficult to argue with him.

Dave Grohl grew up in Springfield, Virginia, a short drive away from Washington DC. The US capital was a hothouse for the early-80s punk and hardcore scene, and the teenage Grohl threw himself into it as both a fan and a musician. He felt at home there, surrounded by two or three hundred other misfits in the moshpit of some DC sweatbox or maybe playing on stage with his early band Scream. But while he embraced punk rock, he didn’t commit to some of its more exclusionist dogma.

“In the punk scene, there was this anti-hero, fuck-classic-rock’n’roll mentality,” he says. “And I understood, culturally and politically, why a lot of those punk-rock musicians disagreed with all that stuff. But at the same time I loved The Beatles and AC/DC. That music had my heart too. I’d go to this sweaty punk rock show, and then I would go home and listen to fucking Foghat, and not think it was a crime. [Mock-huffily] ‘I think I’m allowed to do both.’”

Still, he carried that punk-rock spirit with him when he schlepped up to Seattle in 1989 to join a second-tier grunge band called Nirvana. Nobody, least of all Dave Grohl, expected them to become the defining rock band of the 90s.

“When I first joined the band it was so much fun,” he says. “I lived on the couch in Kurt’s living room, we rehearsed in a barn, we set up our gear and played those songs and people bounced around and got hot and sweaty. I really loved the connection and the appreciation that Nirvana’s audience had with the band.

“And then there was a period where we started to feel a bit out of place, as the band got bigger and bigger, as we’re on television shows and pop radio and magazine covers. It felt a little uncomfortable. But I was also the drummer, so I wasn’t the most recognisable person in the band. I could walk in the front door of a Nirvana show and fucking nobody would really hassle me.”

I’m sure that’s not true.

“It’s almost true. My existence in that band was so purely simple. And then things got complicated and much darker. A lot of it had to do with drugs, a lot of it had to do with finally getting to a place that felt completely foreign and not entirely healthy. And over time that proved to be hard to escape from. So yes, there were a lot of really beautiful moments and a lot of really devastating moments. It ran the gamut.”

Kurt Cobain’s suicide in 1994 and the end of Nirvana is well-documented. Since then Grohl has largely steered away from covering his former band’s songs. On the handful of occasions that he has, it’s always been alongside Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic and latter-day touring guitarist Pat Smear rather than with the Foo Fighters. Tellingly, Grohl has never sung any of Cobain’s songs himself, instead preferring to enlist guest vocalists such as Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, Annie Clark of St Vincent, and Joan Jett.

“I wouldn’t feel comfortable singing a song that Kurt sang,” he says. “I feel perfectly at home playing those songs on the drums. And I love playing them with Krist and Pat and another vocalist. I still have dreams that we’re in Nirvana, that we’re still a band. I still dream there’s an empty arena waiting for us to play. But I don’t sit down at home and run through Smells Like Teen Spirit by myself. It’s just a reminder that the person who is responsible for those beautiful songs is no longer with us. It’s bittersweet.”

One of the many Foos-related projects that has been sidelined temporarily by the pandemic is a documentary film Grohl has been working on. Titled What Drives Us, it’s a hymn to the touring life and the romance of rock’n’roll that fuels every band at the very start of their career. As Grohl puts it: “It’s about what makes people throw their lives away and jump in an old van with their buddies and no guarantees that there’ll ever be any reward other than just playing music with your friends.”

Grohl interviewed several of his friends and peers for the film: members of Metallica, Guns N’ Roses, AC/DC, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, U2, Black Flag o does “Everybody had the same story,” he says. “Nobody ever thought: ‘I’m gonna take over the world and become a stadium-class rock icon.’ They were just like: ‘Fuck school, I’m getting in a shitty van with my friends.’ All of them, every single fucking one of them.”

Grohl has ‘got in the van’ twice in his career. The first time was in the 80s, a period that began with his stint as the drummer with Scream and ended with the point Nirvana suddenly went supernova. And then, for some weird reason, he did it again when he was getting the Foo Fighters off the ground.

The start of the Foos has been written about almost as much as the end of his previous group: how, in the aftermath of Kurt Cobain’s death, he recorded a bunch of songs he’d been writing during his time in Nirvana; how those songs became a debut album that was part cathartic exercise, part emotional life raft; how he brought in Pat Smear, Nirvana’s touring guitarist and co-founder of original LA punk rockers The Germs, along with bassist Nate Mendel and drummer William Goldsmith (long-since replaced by Taylor Hawkins) to turn this literal solo project into a band.

“When we started the Foo Fighters I was twentysix years old,” he says. “In 1994 I had some sort of personal awakening or revelation or epiphany that life is worth living every single day. The intention of this band was to look forward to life.”

The Foo Fighters began their first tour in April 1995. Rather than kick things off with a triumphant, headlinegrabbing tour of their own, Grohl opted to open for US underground rock mainstay Mike Watt on a 42-date tour, travelling from city to city in a red splitter van they bought especially for it, earning 750 dollars a day between them.

“It was the toughest itinerary to this day that I’ve ever had in my entire life,” says Grohl. “He’d have eight shows on, one day off, eight shows on, one day off. Sometimes multiple shows on the same day. Sometimes two cities in the same day. When we came home from that tour, everybody had pneumonia, everybody lost fucking thirty pounds.”

In that situation, most people in Grohl’s shoes would have thought: “Hang on, I used to be the drummer in Nirvana. What the hell am I doing this for?”

“No,” he says. “I thought: ‘Hang on, I used to be the drummer in Nirvana. That’s exactly why I should be doing this like this.’ Because after that, every fucking tour was a cakewalk.’”

Despite their attempts to keep it low-key and under control, the Foo Fighters’ career trajectory hit an upswing pretty fast. While their first album took people by surprise (the drummer from Nirvana can do this?), follow-up There Is Nothing Left To Lose proved it was no fluke (that album remains one of the best things Grohl has ever been involved in, up to and including Nirvana).

Since then the Foos haven’t looked back. There have been bumps in the road, of course. At the start of the millennium they came perilously close to ending after a disillusioned Grohl joined Queens Of The Stone Age as drummer on the latter’s 2002 album Songs For The Deaf. “The seven-year itch,” as he calls it today. (There have been other, less existentially threatening side-projects, including the singer’s collaboration with Josh Homme and John Paul Jones in Them Crooked Vultures, and his love-letter to underground metal Probot.).

Throughout it all, the Foos haven’t just endured, they’ve got bigger. Songs such as Learn To Fly, All My Life, Times Like These and Best Of You have become part of the Great American Rock’N’Roll Songbook. Scenes have come and gone – nu metal, garage rock, emo – but the Foo Fighters have endured, a genre of their own.

Asking Dave Grohl why he thinks his band have become rock’s modern standard bearers isn’t much use. “I think the Foo Fighters have, over the years, become one of the best live bands in the world,” is as much as he’ll toot his own horn.

Thankfully, other people have done it for him.

A papal blessing of sorts came in July 2008, when the Foos headlined two nights at London’s 80,000-capacity Wembley Stadium. On the second night, they were joined by Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones for versions of Led Zeppelin’s Rock And Roll and Ramble On. The minute Page and Jones walked out on stage, several things went through Grohl’s head.

“The main thing was: ‘Don’t shit the bed, Dave,’” he says. “Don’t fuck up these songs with two guys from one of my favourite bands. There was a moment towards the end of the show where it started to rain and I got really choked up. I thought: ‘Here we are, we’ve survived all this time, having started this band with this demo tape and the old red van, and now we’re in a stadium full of people singing every word to every song…’”

When asked if the Foo Fighters are as good as Led Zeppelin, he looks like he can’t believe he’s just been asked the question.

“No.”

As good as Kiss? “[Long pause, possibly diplomatic] Different.” As good as Bon Jovi? “No,” he says, recoiling. “That’s asking a lot.”

If you’re thinking of throwing a birthday party, you could do worse than take a leaf out of Dave Grohl’s book. The Foo Fighters played the LA Forum in January 2015, a few days before their frontman turned 46. “We decided to do the show last-minute, and it was like: ‘Let’s call some of my friends,’” he says.

The friends they called for their celebratory, covers-heavy set included (checks list) Slash, Perry Farrell, Tenacious D, Zakk Wylde, Alice Cooper, Dave Lee Roth and Paul Stanley. “It was literally me going through my phone going: ‘Who do I know? Oh, Paul Stanley.’ My daughter goes to school with his daughter. I see him every fucking Friday in assembly. We sit there and we talk about pyrotechnics.”

It’s funny how things turn out sometimes. It’s unlikely that Dave Grohl, Foghat-loving punk rock brat, would ever have envisaged one day playing Rock And Roll All Nite with Paul Stanley and Panama with Dave Lee Roth, or Led Zeppelin songs with Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones, or blasting through the opening of 2112 with members of Rush at the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, or backing Mick Jagger on Saturday Night Live, or getting a surprise call to go and jam with Prince. But that’s where Dave Grohl ends up. Repeatedly. Sure, he’s living the dream of every rock’n’roll fanboy and girl, but he’s also become the modern equivalent of the very people he’s rubbing shoulders with – a bona fide A-list rock star, just like Mick Jagger or Diamond Dave. He’s one of us, but he’s undeniably one of them as well.

There’s one more anecdote about Dave Grohl’s A-list rock’n’roll connections worth squeezing in, because: a) it’s a doozy, and b) it illustrates just how much his peers like and respect him.

Back in 1992, when Grohl was still in Nirvana, there was an almighty backstage bust-up involving Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love on one side and Axl Rose on the other. Names were called, vitriol was spat, portacabins were rocked. It was a real pick-yourside moment.

“We were young and were fucked up and in this bizarre fantasy world of rock’n’roll,” he says. “We were fucking kids. And the years went by and we all realised: ‘Come on, man, life is too short.’”

Grohl bumped into various members of Guns N’ Roses in the ensuing two decades, and even appeared on Slash’s debut solo album in 2010. Then in 2017 he got a call from Duff McKagan: “Have you still got the throne?” Duff was talking about the throne of guitars that he’d had made after breaking his leg when he fell off the stage at a gig in Sweden in 2015. Axl had busted his foot during GN’R’s reunion show at the Roxy club in LA, and their come back tour was in jeopardy. Could GN’R borrow the throne? Grohl could have said no. But naturally he said yes. And saved the biggest rock’n’roll tour of the decade.

“So Axl took it out with Guns N’ Roses, then he took it out with AC/DC, and then all of a sudden I became the guy you come to if you break a limb on tour, like Thrones R Us.”

How did Axl thank him? A box of chocolates? A bunch of flowers?

“He had Slash go pick me a guitar. And he picked me an early-60s Gibson ES 335 Dot, which to this day is the nicest fucking guitar I have ever played in my life. It was an incredibly kind and classy gesture, and I was very appreciative.”

The circle was properly clos ed in June 2018, when the Foo Fighters brought out Axl, Slash and Duff to join the band to play a cover of Guns’ It’s So Easy at a festival in Italy. “Dude, that was the longest, most sustained crowd scream I have ever experienced in my entire life,” says Grohl. “It was fucking incredible.”

You might be reading this and thinking: “Dave Grohl is one lucky bastard.” And in many ways he is. But you don’t get to be that lucky a bastard without having determination, dedication and big dollop of talent.

If you want to get a sense of the way Grohl really operates, check out Play, the 22-minute instrumental solo track he released under his own name in 2018.

“A lot of that had to do with me proving to myself that I could do it,” he says. “That was something I had never even attempted – a twenty-three-minute-long song where I had to play the instruments from beginning to end without fucking it up. It was like an obstacle course in my mind. Some kids love playing videogames, some kids love playing football. To me, that’s my sport – let me see if I can pull this off. That runs as a thread through my entire career. Let’s see if I can actually be the singer of the band. Let’s see if we can actually play a fucking festival. Let’s see if we can play Wembley Stadium… Every step of the way, I just want to see if we can do it. And once you achieve that, you just push it out the way and go: ‘What’s next?’”

For all his band’s massive success, and the underlying ambition that drives it, Dave Grohl always defaults to his old friend Lemmy in matters of rock’n’roll. And let’s face it, there are worse people to have as your spirit guide.

“I always appreciated and respected him as someone who was entirely real,” he says of the late Motörhead leader. “There was no bullshit there. He was straight, he was to-the-point. And he had an outlaw glimmer in his eye that showed his sense of humour. And I think it’s important in this weird world of playing in a band that your sense of humour stays intact. Taking this shit too seriously can be the death of any band.”

Words: Dave Everley Pics: Danny Clinch

“When we started the Foo Fighters I was twentysix years old,” he says. “In 1994 I had some sort of personal awakening or revelation or epiphany that life is worth living every single day. The intention of this band was to look forward to life.”

The Foo Fighters began their first tour in April 1995. Rather than kick things off with a triumphant, headlinegrabbing tour of their own, Grohl opted to open for US underground rock mainstay Mike Watt on a 42-date tour, travelling from city to city in a red splitter van they bought especially for it, earning 750 dollars a day between them.

“It was the toughest itinerary to this day that I’ve ever had in my entire life,” says Grohl. “He’d have eight shows on, one day off, eight shows on, one day off. Sometimes multiple shows on the same day. Sometimes two cities in the same day. When we came home from that tour, everybody had pneumonia, everybody lost fucking thirty pounds.”

In that situation, most people in Grohl’s shoes would have thought: “Hang on, I used to be the drummer in Nirvana. What the hell am I doing this for?”

“No,” he says. “I thought: ‘Hang on, I used to be the drummer in Nirvana. That’s exactly why I should be doing this like this.’ Because after that, every fucking tour was a cakewalk.’”

Despite their attempts to keep it low-key and under control, the Foo Fighters’ career trajectory hit an upswing pretty fast. While their first album took people by surprise (the drummer from Nirvana can do this?), follow-up There Is Nothing Left To Lose proved it was no fluke (that album remains one of the best things Grohl has ever been involved in, up to and including Nirvana).

Since then the Foos haven’t looked back. There have been bumps in the road, of course. At the start of the millennium they came perilously close to ending after a disillusioned Grohl joined Queens Of The Stone Age as drummer on the latter’s 2002 album Songs For The Deaf. “The seven-year itch,” as he calls it today. (There have been other, less existentially threatening side-projects, including the singer’s collaboration with Josh Homme and John Paul Jones in Them Crooked Vultures, and his love-letter to underground metal Probot.).

Throughout it all, the Foos haven’t just endured, they’ve got bigger. Songs such as Learn To Fly, All My Life, Times Like These and Best Of You have become part of the Great American Rock’N’Roll Songbook. Scenes have come and gone – nu metal, garage rock, emo – but the Foo Fighters have endured, a genre of their own.

Asking Dave Grohl why he thinks his band have become rock’s modern standard bearers isn’t much use. “I think the Foo Fighters have, over the years, become one of the best live bands in the world,” is as much as he’ll toot his own horn.

Thankfully, other people have done it for him.

A papal blessing of sorts came in July 2008, when the Foos headlined two nights at London’s 80,000-capacity Wembley Stadium. On the second night, they were joined by Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones for versions of Led Zeppelin’s Rock And Roll and Ramble On. The minute Page and Jones walked out on stage, several things went through Grohl’s head.

“The main thing was: ‘Don’t shit the bed, Dave,’” he says. “Don’t fuck up these songs with two guys from one of my favourite bands. There was a moment towards the end of the show where it started to rain and I got really choked up. I thought: ‘Here we are, we’ve survived all this time, having started this band with this demo tape and the old red van, and now we’re in a stadium full of people singing every word to every song…’”

When asked if the Foo Fighters are as good as Led Zeppelin, he looks like he can’t believe he’s just been asked the question.

“No.”

As good as Kiss? “[Long pause, possibly diplomatic] Different.” As good as Bon Jovi? “No,” he says, recoiling. “That’s asking a lot.”

If you’re thinking of throwing a birthday party, you could do worse than take a leaf out of Dave Grohl’s book. The Foo Fighters played the LA Forum in January 2015, a few days before their frontman turned 46. “We decided to do the show last-minute, and it was like: ‘Let’s call some of my friends,’” he says.

The friends they called for their celebratory, covers-heavy set included (checks list) Slash, Perry Farrell, Tenacious D, Zakk Wylde, Alice Cooper, Dave Lee Roth and Paul Stanley. “It was literally me going through my phone going: ‘Who do I know? Oh, Paul Stanley.’ My daughter goes to school with his daughter. I see him every fucking Friday in assembly. We sit there and we talk about pyrotechnics.”

It’s funny how things turn out sometimes. It’s unlikely that Dave Grohl, Foghat-loving punk rock brat, would ever have envisaged one day playing Rock And Roll All Nite with Paul Stanley and Panama with Dave Lee Roth, or Led Zeppelin songs with Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones, or blasting through the opening of 2112 with members of Rush at the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, or backing Mick Jagger on Saturday Night Live, or getting a surprise call to go and jam with Prince. But that’s where Dave Grohl ends up. Repeatedly. Sure, he’s living the dream of every rock’n’roll fanboy and girl, but he’s also become the modern equivalent of the very people he’s rubbing shoulders with – a bona fide A-list rock star, just like Mick Jagger or Diamond Dave. He’s one of us, but he’s undeniably one of them as well.

There’s one more anecdote about Dave Grohl’s A-list rock’n’roll connections worth squeezing in, because: a) it’s a doozy, and b) it illustrates just how much his peers like and respect him.

Back in 1992, when Grohl was still in Nirvana, there was an almighty backstage bust-up involving Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love on one side and Axl Rose on the other. Names were called, vitriol was spat, portacabins were rocked. It was a real pick-yourside moment.

“We were young and were fucked up and in this bizarre fantasy world of rock’n’roll,” he says. “We were fucking kids. And the years went by and we all realised: ‘Come on, man, life is too short.’”

Grohl bumped into various members of Guns N’ Roses in the ensuing two decades, and even appeared on Slash’s debut solo album in 2010. Then in 2017 he got a call from Duff McKagan: “Have you still got the throne?” Duff was talking about the throne of guitars that he’d had made after breaking his leg when he fell off the stage at a gig in Sweden in 2015. Axl had busted his foot during GN’R’s reunion show at the Roxy club in LA, and their come back tour was in jeopardy. Could GN’R borrow the throne? Grohl could have said no. But naturally he said yes. And saved the biggest rock’n’roll tour of the decade.

“So Axl took it out with Guns N’ Roses, then he took it out with AC/DC, and then all of a sudden I became the guy you come to if you break a limb on tour, like Thrones R Us.”

How did Axl thank him? A box of chocolates? A bunch of flowers?

“He had Slash go pick me a guitar. And he picked me an early-60s Gibson ES 335 Dot, which to this day is the nicest fucking guitar I have ever played in my life. It was an incredibly kind and classy gesture, and I was very appreciative.”

The circle was properly clos ed in June 2018, when the Foo Fighters brought out Axl, Slash and Duff to join the band to play a cover of Guns’ It’s So Easy at a festival in Italy. “Dude, that was the longest, most sustained crowd scream I have ever experienced in my entire life,” says Grohl. “It was fucking incredible.”

You might be reading this and thinking: “Dave Grohl is one lucky bastard.” And in many ways he is. But you don’t get to be that lucky a bastard without having determination, dedication and big dollop of talent.

If you want to get a sense of the way Grohl really operates, check out Play, the 22-minute instrumental solo track he released under his own name in 2018.

“A lot of that had to do with me proving to myself that I could do it,” he says. “That was something I had never even attempted – a twenty-three-minute-long song where I had to play the instruments from beginning to end without fucking it up. It was like an obstacle course in my mind. Some kids love playing videogames, some kids love playing football. To me, that’s my sport – let me see if I can pull this off. That runs as a thread through my entire career. Let’s see if I can actually be the singer of the band. Let’s see if we can actually play a fucking festival. Let’s see if we can play Wembley Stadium… Every step of the way, I just want to see if we can do it. And once you achieve that, you just push it out the way and go: ‘What’s next?’”

For all his band’s massive success, and the underlying ambition that drives it, Dave Grohl always defaults to his old friend Lemmy in matters of rock’n’roll. And let’s face it, there are worse people to have as your spirit guide.

“I always appreciated and respected him as someone who was entirely real,” he says of the late Motörhead leader. “There was no bullshit there. He was straight, he was to-the-point. And he had an outlaw glimmer in his eye that showed his sense of humour. And I think it’s important in this weird world of playing in a band that your sense of humour stays intact. Taking this shit too seriously can be the death of any band.”

Words: Dave Everley Pics: Danny Clinch

“Well,” Grohl says decisively, “I’m your man for that.” 2020 should have been a banner year for the Foo Fighters. As well as the intended release of the new album, it also marked the 25th anniversary of both their self titled debut and the formation of the Foos as an actual band, as opposed to a one-man project in which Dave Grohl played everything including the kitchen sink. “Oh god, man, we had a world domination scheme that lasted for eighteen months,” he says of the band’s pre-covid plans. “It had movies and documentaries and special gigs, and then that all kind of disappeared. We hit pause on everything in March and we all kind of retreated and went our different ways. I had a break for the first time in ten years, which was the most unusual feeling.” Six months after it was originally due to be released, Medicine At Midnight is headbutting the cage door, clamouring to be let out. It was recorded in a fast and furious few weeks at the end of 2019, in a big old rented house in Encino, California. Strange things happened there. More than one member of the Foo Fighters thought the property was haunted. “Oh, weird shit definitely happened,” says Grohl, although he won’t be drawn any further than that. Most of Foo Fighters’ recent albums have had an angle. There’s been the half electric/half-acoustic double album (2005’s In Your Honor), the back-to-basics garage record (2011’s excellent Wasting Light), the record of the documentary (2015’s star-studded Sonic Highways), the ‘Slayer meets the Beach Boys’ mashup record (2017’s Concrete And Gold). And Medicine At Midnight? If Grohl is to be believed, this is the Foo Fighters’ party record. “I thought rather than overcomplicate things and try to make this riffy prog rock record, which is a type of music we love, let’s simplify everything and make the choruses bigger and the grooves fatter and the tempos more up, so people will bounce around for three hours when we eventually get to play it live,” he explains. “You know when your parents start getting older and wearing things that they shouldn’t wear in public? That might be what the Foo Fighters are doing right now.” He uses the word ‘disco’ to describe the ninetrack album, and that snappy summary broadly fits songs such as quirky lead-off single Shame, Shame, with its snapping drum loops, and the defiantly funky title track. But it’s less John Travolta-in-awhite-suit, more The Game-era Queen or early-80s Bowie. “Most Bowie purists would tear me to fucking shreds for saying Let’s Dance is my favourite Bowie record,” he says. “But honestly, as a drummer listening to Omar Hakim and Tony Thompson [both of whom played on Let’s Dance], I’m, like: ‘Wow, they really incorporated this heavy funk into a lot of their songs.’ Those songs were danceable. I wanted to make a Foo Fighters album people could dance to.”

Still, Medicine At Midnight doesn’t spend too much time showing off its Tony Manero moves before reverting to type. The speedy No Son Of Mine nods back to Grohl’s punk roots, while Waiting On A War and blockbusting closer Love Dies Young are arena-ready anthems that share DNA with past Foos megahits The One and All My Life. It’s a livewire record, and a joyous one.

“I mean, come on, that’s what we need at the moment, right?” he says. And it’s difficult to argue with him.

Dave Grohl grew up in Springfield, Virginia, a short drive away from Washington DC. The US capital was a hothouse for the early-80s punk and hardcore scene, and the teenage Grohl threw himself into it as both a fan and a musician. He felt at home there, surrounded by two or three hundred other misfits in the moshpit of some DC sweatbox or maybe playing on stage with his early band Scream. But while he embraced punk rock, he didn’t commit to some of its more exclusionist dogma.

“In the punk scene, there was this anti-hero, fuck-classic-rock’n’roll mentality,” he says. “And I understood, culturally and politically, why a lot of those punk-rock musicians disagreed with all that stuff. But at the same time I loved The Beatles and AC/DC. That music had my heart too. I’d go to this sweaty punk rock show, and then I would go home and listen to fucking Foghat, and not think it was a crime. [Mock-huffily] ‘I think I’m allowed to do both.’”

Still, he carried that punk-rock spirit with him when he schlepped up to Seattle in 1989 to join a second-tier grunge band called Nirvana. Nobody, least of all Dave Grohl, expected them to become the defining rock band of the 90s.

“When I first joined the band it was so much fun,” he says. “I lived on the couch in Kurt’s living room, we rehearsed in a barn, we set up our gear and played those songs and people bounced around and got hot and sweaty. I really loved the connection and the appreciation that Nirvana’s audience had with the band.

“And then there was a period where we started to feel a bit out of place, as the band got bigger and bigger, as we’re on television shows and pop radio and magazine covers. It felt a little uncomfortable. But I was also the drummer, so I wasn’t the most recognisable person in the band. I could walk in the front door of a Nirvana show and fucking nobody would really hassle me.”

I’m sure that’s not true.

“It’s almost true. My existence in that band was so purely simple. And then things got complicated and much darker. A lot of it had to do with drugs, a lot of it had to do with finally getting to a place that felt completely foreign and not entirely healthy. And over time that proved to be hard to escape from. So yes, there were a lot of really beautiful moments and a lot of really devastating moments. It ran the gamut.”

Kurt Cobain’s suicide in 1994 and the end of Nirvana is well-documented. Since then Grohl has largely steered away from covering his former band’s songs. On the handful of occasions that he has, it’s always been alongside Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic and latter-day touring guitarist Pat Smear rather than with the Foo Fighters. Tellingly, Grohl has never sung any of Cobain’s songs himself, instead preferring to enlist guest vocalists such as Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, Annie Clark of St Vincent, and Joan Jett.

“I wouldn’t feel comfortable singing a song that Kurt sang,” he says. “I feel perfectly at home playing those songs on the drums. And I love playing them with Krist and Pat and another vocalist. I still have dreams that we’re in Nirvana, that we’re still a band. I still dream there’s an empty arena waiting for us to play. But I don’t sit down at home and run through Smells Like Teen Spirit by myself. It’s just a reminder that the person who is responsible for those beautiful songs is no longer with us. It’s bittersweet.”

One of the many Foos-related projects that has been sidelined temporarily by the pandemic is a documentary film Grohl has been working on. Titled What Drives Us, it’s a hymn to the touring life and the romance of rock’n’roll that fuels every band at the very start of their career. As Grohl puts it: “It’s about what makes people throw their lives away and jump in an old van with their buddies and no guarantees that there’ll ever be any reward other than just playing music with your friends.”

Grohl interviewed several of his friends and peers for the film: members of Metallica, Guns N’ Roses, AC/DC, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, U2, Black Flag o does “Everybody had the same story,” he says. “Nobody ever thought: ‘I’m gonna take over the world and become a stadium-class rock icon.’ They were just like: ‘Fuck school, I’m getting in a shitty van with my friends.’ All of them, every single fucking one of them.”

Grohl has ‘got in the van’ twice in his career. The first time was in the 80s, a period that began with his stint as the drummer with Scream and ended with the point Nirvana suddenly went supernova. And then, for some weird reason, he did it again when he was getting the Foo Fighters off the ground.

The start of the Foos has been written about almost as much as the end of his previous group: how, in the aftermath of Kurt Cobain’s death, he recorded a bunch of songs he’d been writing during his time in Nirvana; how those songs became a debut album that was part cathartic exercise, part emotional life raft; how he brought in Pat Smear, Nirvana’s touring guitarist and co-founder of original LA punk rockers The Germs, along with bassist Nate Mendel and drummer William Goldsmith (long-since replaced by Taylor Hawkins) to turn this literal solo project into a band.

Still, Medicine At Midnight doesn’t spend too much time showing off its Tony Manero moves before reverting to type. The speedy No Son Of Mine nods back to Grohl’s punk roots, while Waiting On A War and blockbusting closer Love Dies Young are arena-ready anthems that share DNA with past Foos megahits The One and All My Life. It’s a livewire record, and a joyous one.

“I mean, come on, that’s what we need at the moment, right?” he says. And it’s difficult to argue with him.

Dave Grohl grew up in Springfield, Virginia, a short drive away from Washington DC. The US capital was a hothouse for the early-80s punk and hardcore scene, and the teenage Grohl threw himself into it as both a fan and a musician. He felt at home there, surrounded by two or three hundred other misfits in the moshpit of some DC sweatbox or maybe playing on stage with his early band Scream. But while he embraced punk rock, he didn’t commit to some of its more exclusionist dogma.

“In the punk scene, there was this anti-hero, fuck-classic-rock’n’roll mentality,” he says. “And I understood, culturally and politically, why a lot of those punk-rock musicians disagreed with all that stuff. But at the same time I loved The Beatles and AC/DC. That music had my heart too. I’d go to this sweaty punk rock show, and then I would go home and listen to fucking Foghat, and not think it was a crime. [Mock-huffily] ‘I think I’m allowed to do both.’”

Still, he carried that punk-rock spirit with him when he schlepped up to Seattle in 1989 to join a second-tier grunge band called Nirvana. Nobody, least of all Dave Grohl, expected them to become the defining rock band of the 90s.

“When I first joined the band it was so much fun,” he says. “I lived on the couch in Kurt’s living room, we rehearsed in a barn, we set up our gear and played those songs and people bounced around and got hot and sweaty. I really loved the connection and the appreciation that Nirvana’s audience had with the band.

“And then there was a period where we started to feel a bit out of place, as the band got bigger and bigger, as we’re on television shows and pop radio and magazine covers. It felt a little uncomfortable. But I was also the drummer, so I wasn’t the most recognisable person in the band. I could walk in the front door of a Nirvana show and fucking nobody would really hassle me.”

I’m sure that’s not true.

“It’s almost true. My existence in that band was so purely simple. And then things got complicated and much darker. A lot of it had to do with drugs, a lot of it had to do with finally getting to a place that felt completely foreign and not entirely healthy. And over time that proved to be hard to escape from. So yes, there were a lot of really beautiful moments and a lot of really devastating moments. It ran the gamut.”

Kurt Cobain’s suicide in 1994 and the end of Nirvana is well-documented. Since then Grohl has largely steered away from covering his former band’s songs. On the handful of occasions that he has, it’s always been alongside Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic and latter-day touring guitarist Pat Smear rather than with the Foo Fighters. Tellingly, Grohl has never sung any of Cobain’s songs himself, instead preferring to enlist guest vocalists such as Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, Annie Clark of St Vincent, and Joan Jett.

“I wouldn’t feel comfortable singing a song that Kurt sang,” he says. “I feel perfectly at home playing those songs on the drums. And I love playing them with Krist and Pat and another vocalist. I still have dreams that we’re in Nirvana, that we’re still a band. I still dream there’s an empty arena waiting for us to play. But I don’t sit down at home and run through Smells Like Teen Spirit by myself. It’s just a reminder that the person who is responsible for those beautiful songs is no longer with us. It’s bittersweet.”

One of the many Foos-related projects that has been sidelined temporarily by the pandemic is a documentary film Grohl has been working on. Titled What Drives Us, it’s a hymn to the touring life and the romance of rock’n’roll that fuels every band at the very start of their career. As Grohl puts it: “It’s about what makes people throw their lives away and jump in an old van with their buddies and no guarantees that there’ll ever be any reward other than just playing music with your friends.”

Grohl interviewed several of his friends and peers for the film: members of Metallica, Guns N’ Roses, AC/DC, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, U2, Black Flag o does “Everybody had the same story,” he says. “Nobody ever thought: ‘I’m gonna take over the world and become a stadium-class rock icon.’ They were just like: ‘Fuck school, I’m getting in a shitty van with my friends.’ All of them, every single fucking one of them.”

Grohl has ‘got in the van’ twice in his career. The first time was in the 80s, a period that began with his stint as the drummer with Scream and ended with the point Nirvana suddenly went supernova. And then, for some weird reason, he did it again when he was getting the Foo Fighters off the ground.

The start of the Foos has been written about almost as much as the end of his previous group: how, in the aftermath of Kurt Cobain’s death, he recorded a bunch of songs he’d been writing during his time in Nirvana; how those songs became a debut album that was part cathartic exercise, part emotional life raft; how he brought in Pat Smear, Nirvana’s touring guitarist and co-founder of original LA punk rockers The Germs, along with bassist Nate Mendel and drummer William Goldsmith (long-since replaced by Taylor Hawkins) to turn this literal solo project into a band.

“When we started the Foo Fighters I was twentysix years old,” he says. “In 1994 I had some sort of personal awakening or revelation or epiphany that life is worth living every single day. The intention of this band was to look forward to life.”

The Foo Fighters began their first tour in April 1995. Rather than kick things off with a triumphant, headlinegrabbing tour of their own, Grohl opted to open for US underground rock mainstay Mike Watt on a 42-date tour, travelling from city to city in a red splitter van they bought especially for it, earning 750 dollars a day between them.

“It was the toughest itinerary to this day that I’ve ever had in my entire life,” says Grohl. “He’d have eight shows on, one day off, eight shows on, one day off. Sometimes multiple shows on the same day. Sometimes two cities in the same day. When we came home from that tour, everybody had pneumonia, everybody lost fucking thirty pounds.”

In that situation, most people in Grohl’s shoes would have thought: “Hang on, I used to be the drummer in Nirvana. What the hell am I doing this for?”

“No,” he says. “I thought: ‘Hang on, I used to be the drummer in Nirvana. That’s exactly why I should be doing this like this.’ Because after that, every fucking tour was a cakewalk.’”

Despite their attempts to keep it low-key and under control, the Foo Fighters’ career trajectory hit an upswing pretty fast. While their first album took people by surprise (the drummer from Nirvana can do this?), follow-up There Is Nothing Left To Lose proved it was no fluke (that album remains one of the best things Grohl has ever been involved in, up to and including Nirvana).

Since then the Foos haven’t looked back. There have been bumps in the road, of course. At the start of the millennium they came perilously close to ending after a disillusioned Grohl joined Queens Of The Stone Age as drummer on the latter’s 2002 album Songs For The Deaf. “The seven-year itch,” as he calls it today. (There have been other, less existentially threatening side-projects, including the singer’s collaboration with Josh Homme and John Paul Jones in Them Crooked Vultures, and his love-letter to underground metal Probot.).

Throughout it all, the Foos haven’t just endured, they’ve got bigger. Songs such as Learn To Fly, All My Life, Times Like These and Best Of You have become part of the Great American Rock’N’Roll Songbook. Scenes have come and gone – nu metal, garage rock, emo – but the Foo Fighters have endured, a genre of their own.

Asking Dave Grohl why he thinks his band have become rock’s modern standard bearers isn’t much use. “I think the Foo Fighters have, over the years, become one of the best live bands in the world,” is as much as he’ll toot his own horn.

Thankfully, other people have done it for him.

A papal blessing of sorts came in July 2008, when the Foos headlined two nights at London’s 80,000-capacity Wembley Stadium. On the second night, they were joined by Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones for versions of Led Zeppelin’s Rock And Roll and Ramble On. The minute Page and Jones walked out on stage, several things went through Grohl’s head.

“The main thing was: ‘Don’t shit the bed, Dave,’” he says. “Don’t fuck up these songs with two guys from one of my favourite bands. There was a moment towards the end of the show where it started to rain and I got really choked up. I thought: ‘Here we are, we’ve survived all this time, having started this band with this demo tape and the old red van, and now we’re in a stadium full of people singing every word to every song…’”

When asked if the Foo Fighters are as good as Led Zeppelin, he looks like he can’t believe he’s just been asked the question.

“No.”

As good as Kiss? “[Long pause, possibly diplomatic] Different.” As good as Bon Jovi? “No,” he says, recoiling. “That’s asking a lot.”

If you’re thinking of throwing a birthday party, you could do worse than take a leaf out of Dave Grohl’s book. The Foo Fighters played the LA Forum in January 2015, a few days before their frontman turned 46. “We decided to do the show last-minute, and it was like: ‘Let’s call some of my friends,’” he says.

The friends they called for their celebratory, covers-heavy set included (checks list) Slash, Perry Farrell, Tenacious D, Zakk Wylde, Alice Cooper, Dave Lee Roth and Paul Stanley. “It was literally me going through my phone going: ‘Who do I know? Oh, Paul Stanley.’ My daughter goes to school with his daughter. I see him every fucking Friday in assembly. We sit there and we talk about pyrotechnics.”

It’s funny how things turn out sometimes. It’s unlikely that Dave Grohl, Foghat-loving punk rock brat, would ever have envisaged one day playing Rock And Roll All Nite with Paul Stanley and Panama with Dave Lee Roth, or Led Zeppelin songs with Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones, or blasting through the opening of 2112 with members of Rush at the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, or backing Mick Jagger on Saturday Night Live, or getting a surprise call to go and jam with Prince. But that’s where Dave Grohl ends up. Repeatedly. Sure, he’s living the dream of every rock’n’roll fanboy and girl, but he’s also become the modern equivalent of the very people he’s rubbing shoulders with – a bona fide A-list rock star, just like Mick Jagger or Diamond Dave. He’s one of us, but he’s undeniably one of them as well.

There’s one more anecdote about Dave Grohl’s A-list rock’n’roll connections worth squeezing in, because: a) it’s a doozy, and b) it illustrates just how much his peers like and respect him.

Back in 1992, when Grohl was still in Nirvana, there was an almighty backstage bust-up involving Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love on one side and Axl Rose on the other. Names were called, vitriol was spat, portacabins were rocked. It was a real pick-yourside moment.

“We were young and were fucked up and in this bizarre fantasy world of rock’n’roll,” he says. “We were fucking kids. And the years went by and we all realised: ‘Come on, man, life is too short.’”

Grohl bumped into various members of Guns N’ Roses in the ensuing two decades, and even appeared on Slash’s debut solo album in 2010. Then in 2017 he got a call from Duff McKagan: “Have you still got the throne?” Duff was talking about the throne of guitars that he’d had made after breaking his leg when he fell off the stage at a gig in Sweden in 2015. Axl had busted his foot during GN’R’s reunion show at the Roxy club in LA, and their come back tour was in jeopardy. Could GN’R borrow the throne? Grohl could have said no. But naturally he said yes. And saved the biggest rock’n’roll tour of the decade.

“So Axl took it out with Guns N’ Roses, then he took it out with AC/DC, and then all of a sudden I became the guy you come to if you break a limb on tour, like Thrones R Us.”

How did Axl thank him? A box of chocolates? A bunch of flowers?

“He had Slash go pick me a guitar. And he picked me an early-60s Gibson ES 335 Dot, which to this day is the nicest fucking guitar I have ever played in my life. It was an incredibly kind and classy gesture, and I was very appreciative.”

The circle was properly clos ed in June 2018, when the Foo Fighters brought out Axl, Slash and Duff to join the band to play a cover of Guns’ It’s So Easy at a festival in Italy. “Dude, that was the longest, most sustained crowd scream I have ever experienced in my entire life,” says Grohl. “It was fucking incredible.”

You might be reading this and thinking: “Dave Grohl is one lucky bastard.” And in many ways he is. But you don’t get to be that lucky a bastard without having determination, dedication and big dollop of talent.

If you want to get a sense of the way Grohl really operates, check out Play, the 22-minute instrumental solo track he released under his own name in 2018.

“A lot of that had to do with me proving to myself that I could do it,” he says. “That was something I had never even attempted – a twenty-three-minute-long song where I had to play the instruments from beginning to end without fucking it up. It was like an obstacle course in my mind. Some kids love playing videogames, some kids love playing football. To me, that’s my sport – let me see if I can pull this off. That runs as a thread through my entire career. Let’s see if I can actually be the singer of the band. Let’s see if we can actually play a fucking festival. Let’s see if we can play Wembley Stadium… Every step of the way, I just want to see if we can do it. And once you achieve that, you just push it out the way and go: ‘What’s next?’”

For all his band’s massive success, and the underlying ambition that drives it, Dave Grohl always defaults to his old friend Lemmy in matters of rock’n’roll. And let’s face it, there are worse people to have as your spirit guide.

“I always appreciated and respected him as someone who was entirely real,” he says of the late Motörhead leader. “There was no bullshit there. He was straight, he was to-the-point. And he had an outlaw glimmer in his eye that showed his sense of humour. And I think it’s important in this weird world of playing in a band that your sense of humour stays intact. Taking this shit too seriously can be the death of any band.”

Words: Dave Everley Pics: Danny Clinch

“When we started the Foo Fighters I was twentysix years old,” he says. “In 1994 I had some sort of personal awakening or revelation or epiphany that life is worth living every single day. The intention of this band was to look forward to life.”

The Foo Fighters began their first tour in April 1995. Rather than kick things off with a triumphant, headlinegrabbing tour of their own, Grohl opted to open for US underground rock mainstay Mike Watt on a 42-date tour, travelling from city to city in a red splitter van they bought especially for it, earning 750 dollars a day between them.

“It was the toughest itinerary to this day that I’ve ever had in my entire life,” says Grohl. “He’d have eight shows on, one day off, eight shows on, one day off. Sometimes multiple shows on the same day. Sometimes two cities in the same day. When we came home from that tour, everybody had pneumonia, everybody lost fucking thirty pounds.”

In that situation, most people in Grohl’s shoes would have thought: “Hang on, I used to be the drummer in Nirvana. What the hell am I doing this for?”

“No,” he says. “I thought: ‘Hang on, I used to be the drummer in Nirvana. That’s exactly why I should be doing this like this.’ Because after that, every fucking tour was a cakewalk.’”

Despite their attempts to keep it low-key and under control, the Foo Fighters’ career trajectory hit an upswing pretty fast. While their first album took people by surprise (the drummer from Nirvana can do this?), follow-up There Is Nothing Left To Lose proved it was no fluke (that album remains one of the best things Grohl has ever been involved in, up to and including Nirvana).

Since then the Foos haven’t looked back. There have been bumps in the road, of course. At the start of the millennium they came perilously close to ending after a disillusioned Grohl joined Queens Of The Stone Age as drummer on the latter’s 2002 album Songs For The Deaf. “The seven-year itch,” as he calls it today. (There have been other, less existentially threatening side-projects, including the singer’s collaboration with Josh Homme and John Paul Jones in Them Crooked Vultures, and his love-letter to underground metal Probot.).

Throughout it all, the Foos haven’t just endured, they’ve got bigger. Songs such as Learn To Fly, All My Life, Times Like These and Best Of You have become part of the Great American Rock’N’Roll Songbook. Scenes have come and gone – nu metal, garage rock, emo – but the Foo Fighters have endured, a genre of their own.

Asking Dave Grohl why he thinks his band have become rock’s modern standard bearers isn’t much use. “I think the Foo Fighters have, over the years, become one of the best live bands in the world,” is as much as he’ll toot his own horn.

Thankfully, other people have done it for him.

A papal blessing of sorts came in July 2008, when the Foos headlined two nights at London’s 80,000-capacity Wembley Stadium. On the second night, they were joined by Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones for versions of Led Zeppelin’s Rock And Roll and Ramble On. The minute Page and Jones walked out on stage, several things went through Grohl’s head.

“The main thing was: ‘Don’t shit the bed, Dave,’” he says. “Don’t fuck up these songs with two guys from one of my favourite bands. There was a moment towards the end of the show where it started to rain and I got really choked up. I thought: ‘Here we are, we’ve survived all this time, having started this band with this demo tape and the old red van, and now we’re in a stadium full of people singing every word to every song…’”

When asked if the Foo Fighters are as good as Led Zeppelin, he looks like he can’t believe he’s just been asked the question.

“No.”

As good as Kiss? “[Long pause, possibly diplomatic] Different.” As good as Bon Jovi? “No,” he says, recoiling. “That’s asking a lot.”

If you’re thinking of throwing a birthday party, you could do worse than take a leaf out of Dave Grohl’s book. The Foo Fighters played the LA Forum in January 2015, a few days before their frontman turned 46. “We decided to do the show last-minute, and it was like: ‘Let’s call some of my friends,’” he says.

The friends they called for their celebratory, covers-heavy set included (checks list) Slash, Perry Farrell, Tenacious D, Zakk Wylde, Alice Cooper, Dave Lee Roth and Paul Stanley. “It was literally me going through my phone going: ‘Who do I know? Oh, Paul Stanley.’ My daughter goes to school with his daughter. I see him every fucking Friday in assembly. We sit there and we talk about pyrotechnics.”

It’s funny how things turn out sometimes. It’s unlikely that Dave Grohl, Foghat-loving punk rock brat, would ever have envisaged one day playing Rock And Roll All Nite with Paul Stanley and Panama with Dave Lee Roth, or Led Zeppelin songs with Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones, or blasting through the opening of 2112 with members of Rush at the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, or backing Mick Jagger on Saturday Night Live, or getting a surprise call to go and jam with Prince. But that’s where Dave Grohl ends up. Repeatedly. Sure, he’s living the dream of every rock’n’roll fanboy and girl, but he’s also become the modern equivalent of the very people he’s rubbing shoulders with – a bona fide A-list rock star, just like Mick Jagger or Diamond Dave. He’s one of us, but he’s undeniably one of them as well.

There’s one more anecdote about Dave Grohl’s A-list rock’n’roll connections worth squeezing in, because: a) it’s a doozy, and b) it illustrates just how much his peers like and respect him.

Back in 1992, when Grohl was still in Nirvana, there was an almighty backstage bust-up involving Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love on one side and Axl Rose on the other. Names were called, vitriol was spat, portacabins were rocked. It was a real pick-yourside moment.

“We were young and were fucked up and in this bizarre fantasy world of rock’n’roll,” he says. “We were fucking kids. And the years went by and we all realised: ‘Come on, man, life is too short.’”

Grohl bumped into various members of Guns N’ Roses in the ensuing two decades, and even appeared on Slash’s debut solo album in 2010. Then in 2017 he got a call from Duff McKagan: “Have you still got the throne?” Duff was talking about the throne of guitars that he’d had made after breaking his leg when he fell off the stage at a gig in Sweden in 2015. Axl had busted his foot during GN’R’s reunion show at the Roxy club in LA, and their come back tour was in jeopardy. Could GN’R borrow the throne? Grohl could have said no. But naturally he said yes. And saved the biggest rock’n’roll tour of the decade.

“So Axl took it out with Guns N’ Roses, then he took it out with AC/DC, and then all of a sudden I became the guy you come to if you break a limb on tour, like Thrones R Us.”

How did Axl thank him? A box of chocolates? A bunch of flowers?

“He had Slash go pick me a guitar. And he picked me an early-60s Gibson ES 335 Dot, which to this day is the nicest fucking guitar I have ever played in my life. It was an incredibly kind and classy gesture, and I was very appreciative.”

The circle was properly clos ed in June 2018, when the Foo Fighters brought out Axl, Slash and Duff to join the band to play a cover of Guns’ It’s So Easy at a festival in Italy. “Dude, that was the longest, most sustained crowd scream I have ever experienced in my entire life,” says Grohl. “It was fucking incredible.”

You might be reading this and thinking: “Dave Grohl is one lucky bastard.” And in many ways he is. But you don’t get to be that lucky a bastard without having determination, dedication and big dollop of talent.

If you want to get a sense of the way Grohl really operates, check out Play, the 22-minute instrumental solo track he released under his own name in 2018.

“A lot of that had to do with me proving to myself that I could do it,” he says. “That was something I had never even attempted – a twenty-three-minute-long song where I had to play the instruments from beginning to end without fucking it up. It was like an obstacle course in my mind. Some kids love playing videogames, some kids love playing football. To me, that’s my sport – let me see if I can pull this off. That runs as a thread through my entire career. Let’s see if I can actually be the singer of the band. Let’s see if we can actually play a fucking festival. Let’s see if we can play Wembley Stadium… Every step of the way, I just want to see if we can do it. And once you achieve that, you just push it out the way and go: ‘What’s next?’”

For all his band’s massive success, and the underlying ambition that drives it, Dave Grohl always defaults to his old friend Lemmy in matters of rock’n’roll. And let’s face it, there are worse people to have as your spirit guide.

“I always appreciated and respected him as someone who was entirely real,” he says of the late Motörhead leader. “There was no bullshit there. He was straight, he was to-the-point. And he had an outlaw glimmer in his eye that showed his sense of humour. And I think it’s important in this weird world of playing in a band that your sense of humour stays intact. Taking this shit too seriously can be the death of any band.”

Words: Dave Everley Pics: Danny Clinch