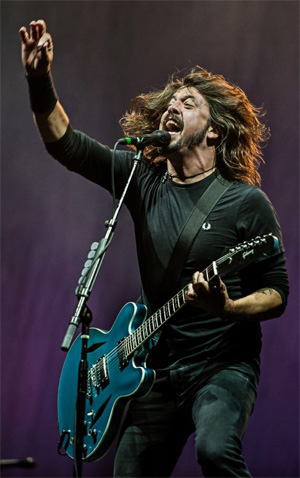

Even a steaming hangover can’t slow Dave Grohl

down. It’s a summer’s day in Los Angeles, and

although the frazzled Foo Fighter rolls into

the band’s Studio 606 clad entirely in black, his

conversation is the usual kaleidoscope of themes.

His kids. Metallica. Animal from The Muppets. And, above all

these, the fiercely ambitious ninth album, Concrete And Gold,

that will scotch any lingering notion of the Foos as Nirvanalite.

“This is something,” he tells us, “I’ve always wanted to do.”

Even a steaming hangover can’t slow Dave Grohl

down. It’s a summer’s day in Los Angeles, and

although the frazzled Foo Fighter rolls into

the band’s Studio 606 clad entirely in black, his

conversation is the usual kaleidoscope of themes.

His kids. Metallica. Animal from The Muppets. And, above all

these, the fiercely ambitious ninth album, Concrete And Gold,

that will scotch any lingering notion of the Foos as Nirvanalite.

“This is something,” he tells us, “I’ve always wanted to do.”By rights, Grohl shouldn’t be on duty. Recent times have been sufficiently tough for this human dynamo to breathe that dirtiest of words: hiatus. To recap, there was the tumble from a Gothenburg stage back in June 2015, the broken leg and the makeshift set-up that saw him installed on a guitar-bedecked throne.

“Well, it’s strange,” he reflects, “because I remember right after surgery, having the phone call with my production crew. We had to cancel four or five shows, but we wanted to finish [the tour]. I knew I couldn’t walk for months, so I thought, ‘OK, I’ll sit down.’ And we drew this diagram and made that crazy throne.

“The first show sitting in that throne was so fucking weird. I’d never sat down and played a rock show in a stadium. And I was nervous, but by the end of the show, I thought, ‘That was weird, and I like things that are weird, so let’s do it more.’”

Grohl’s throne carved out its own small slice of rock’n’roll folklore – especially when it was lent to fellow hobbler Axl Rose. “I went to see Guns N’ Roses and it was a fucking great show, but I was sitting there watching them, like, ‘That’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever seen in my life.’ It’s like watching a king on a throne just sort of conduct an audience.”

But when he dethroned each night, Grohl struggled. “We did fifty or sixty shows after I’d broken my leg and I had a blast. The shows where I was sitting in that ridiculous throne thing, I fucking loved it. But those were the best three hours of the day. It was the other twenty-one hours that were a challenge, because I was on crutches or in a wheelchair. So not only was it physically challenging, but after a while it’s emotionally difficult, so I thought the best thing for the band would be just to stop and get away from it for a while. We’ve always felt like if we get to the point where it’s just about to snap then we back off and say, ‘We should stop,’ y’know?”

This was to be the year the Foo Fighters lay low, dabbled in rainy-day projects, caught up with their longsuffering families. That was never going to work out. As the sprawling master tapes and wall-mounted platinum discs of Studio 606 attest, since he formed the Foos back in 1994, downtime has not been in Grohl’s vocabulary. The frontman soon found himself feeling rudderless, empty, bereft.

“I was approaching other projects, like directing movies and stuff like that, just to do something other than the band, but my passion wasn’t the same. And it actually seemed like work, this other project. I’ve never had to manufacture some inspiration to be in the Foo Fighters. It’s always been real. And here I was trying to create some inspiration or energy to do something else. And I realised, like, ‘Oh, that’s what it’s like when your heart isn’t one hundred per cent in it.’ It was around then I started to realise, like, the best thing for me isn’t a break, it’s to make music with the band.

“It’s hard to spend too much time away,” he says. “I need to play music with these guys. It’s such a big part of my life that when you’re away from it for six months, eight months, whatever it is, you actually feel empty in a way. I thought at one point that music was the thing that was making me exhausted and fucking up my head. But then after six months, I realised: ‘No, no, no, wait. Music is what keeps me from going crazy, y’know?’” So began Concrete And Gold, the new material initiated over five days at an Airbnb in Ojai, California, where Grohl stripped to his underwear, drank heavily then spat whatever came to mind into a portable studio. “When I went to sing these songs,” he says, “I went into that house in the woods for a week just by myself and I would drink a bottle of wine and then scream anything into a microphone. It was like this unfiltered stream of consciousness.”

If Grohl’s testimony suggests that Concrete And Gold is an album of the route-one, three-chord, hit-and-hope variety, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Described by the line-up as “Motörhead’s version of Sgt. Pepper”, this ninth album is the most ambitious of their career, walking a tightrope between savage hard rock and pure pop. The natural conclusion is that this schizophrenic quality is down to a happy tug-of-war with Greg Kurstin, the producer best-known for his pop smashes with Adele and Sia (as well as his own off-kilter outfit, The Bird And The Bee). Grohl says otherwise.

“It’s something I’ve always wanted to do. I’ve always wanted to make a record where musically or instrumentally, or dynamically, it’s really diverse. So every record has its moments of that, whether it’s the first record, or the second record with stuff like February Stars and See You, or In Your Honor, there’s the acoustic side, there’s the rock side.

“But when I met Greg, I realised he’s the person

that’s going to do this bigger and better than we’ve

ever done it before. Like, anywhere you want to go,

he’ll take you farther than you thought you could

go. So if you say, ‘I want this to be really trashy and

noisy,’ then you get a song like La Dee Da, which is

just really, like, fucking noisy. If I say, ‘I want this

to sound really huge, like a choir,’ then you get

a song like Concrete And Gold, where it goes from

being this really spare, dark Black Sabbath riff to

exploding into this mushroom cloud of fucking

choirs. I eventually realised that the [title track]

not only serves as this hopeful finale to the album,

but it also does represent the juxtaposition or the

duality of the sound of the record. There’s that

raw foundation of noisy rock riffs, and then that

beautiful shiny melody and harmony on top.

“But when I met Greg, I realised he’s the person

that’s going to do this bigger and better than we’ve

ever done it before. Like, anywhere you want to go,

he’ll take you farther than you thought you could

go. So if you say, ‘I want this to be really trashy and

noisy,’ then you get a song like La Dee Da, which is

just really, like, fucking noisy. If I say, ‘I want this

to sound really huge, like a choir,’ then you get

a song like Concrete And Gold, where it goes from

being this really spare, dark Black Sabbath riff to

exploding into this mushroom cloud of fucking

choirs. I eventually realised that the [title track]

not only serves as this hopeful finale to the album,

but it also does represent the juxtaposition or the

duality of the sound of the record. There’s that

raw foundation of noisy rock riffs, and then that

beautiful shiny melody and harmony on top.“I grew up listening to The Beatles when I was young,” Grohl continues. “The songs I always loved the most were the ones that were kinda dark and sinister, like She’s So Heavy. It’s almost like the first dark metal riff. It’s like, you just close your eyes and it seems like this fucking sinister, dark vibe. But the vocals are so beautiful, and the lyrics… I mean, the harmonies they would stack are so fucking pretty, and I knew that when I was ten. So that’s sort of written into my DNA zipper musically – that’s my first love. And this time, we’ve actually got to the place where I feel satisfied that we did that one thing that I always wanted to do, y’know?” Then there’s the Concrete And Gold lyric sheet, whose often bleak viewpoint is at odds with Grohl’s sunny-side-up persona, and prompted Josh Homme to note: “Finally, Dave’s made a dark album. It was about time.”

“Well, I had been watching television and thinking about the state of the world and the state of America,” remembers Grohl, “and I went to Ojai and fucking turned the television off. I threw the television out the window and just wanted to play music; disappear. But yeah, I mean, I think the current climate here on planet Earth is a bit disparaging. It seems like there’s so much division and conflict that ultimately all I want to do is bring everyone together to feel some hope or sing a song.

“When you come to a Foo Fighters show,” he continues, “not everybody comes from the same place. They’re from all walks of life and different races, different religions, different nationalities, different languages, but they all manage to come together and sing songs with us, and that to me is the ultimate goal. I don’t want to divide anyone. I want there to be this sort of coexistence, though I feel like there’s a lot of institutions that are placed upon us that really split everyone into so many different factions that you forget about basic common human behaviour.

“When I’m writing lyrics, I’m not so politically direct that it would sound like a Rage Against The Machine album, but what I’m trying to do is express frustration at how everyone is so divided. When we go play live and you’ve got a hundred thousand people singing along to a song, that to me is what life’s all about. Connecting all these people with a lyric or a song or whatever. That’s what gives me hope.”

Arrows could be interpreted as a call-to-arms against President Trump: a song about a character with arrows in his eyes and war on his mind? “One of the beautiful things about lyrics is that you wind up singing those songs for your own reasons. Arrows is actually written about my mother, and the struggles of being a woman and a single parent, trying to raise two kids as a public school teacher, and the struggles that I’d watch her go through. Dirty Water, I think, is just about feeling polluted by that black cloud of oppression. Y’know, where you’re bleeding dirty water and you’re breathing dirty sky, you just kinda feel polluted by that sort of dark energy.”

Other songs, like the cacophonous La Dee Da, with its references to cult leader Jim Jones, find Grohl looking inwards and backwards. “That song is about me as a teenager,” explains Grohl. “When I was twelve or thirteen years old, I started discovering hardcore punk rock, underground music, and I was alienated from most people in my neighbourhood where I lived. I was the only weird punk-rock kid, and there was something empowering about that – I felt good about myself that I was different from everyone else. And this is in the 80s where there’s this conservative wave of politics that was washing over America, with the Reagan administration and Reaganomics, and the country was in this state of conflict, because instead of it being progressive, it seemed regressive. And as a forward-thinking fucking alienated freak, I just felt uncomfortable that: wait a minute, I don’t want life to be like it was in the fifties. I want life to be like it is fucking now. Today.

“There were times where it was difficult,” he reflects, “but I felt proud that I didn’t just go by the same standards as everyone else in life, and so listening to Psychic TV or fucking crazy industrial music in my blue bedroom, where I had mistakenly painted Jim Jones on my wall. I didn’t mean to: I was painting his face on a bedsheet and it stuck to my wall. So when I tore it off, all the paint bled through onto my wall. So over my bed, I had this mural of his face for years. And obviously he was a fucking violent, terrible, crazy fucking person… but I wrote that song about how I still feel alienated in life in so many ways.”

Grohl is a teenager no longer. At 48, black must soon give way to grey, the first hint of the ageing process announced by his thick black spectacles. “Oh God, it’s the worst,” he hoots. “When I was young, I really wanted glasses cos my sister had them. She had braces and glasses. I was so jealous, cos she had all the accoutrements. And then finally, when I turned 40, eight years ago, my optometrist said: ‘Well, you need glasses.’ I was like: ‘Yay! I’m getting glasses!’ Now I’m like: ‘Fuck glasses!’ They drive me crazy. If I forget them I can’t read menus. I ask people to read me the menu. It’s embarrassing. It’s terrible. C’est la vie, mon chéri.”

Breaking your leg, sitting on that throne, getting glasses… have you ever wondered if you might be getting too old for all this? “Oh, I’ve felt like that for the last fifteen years, y’know?” Grohl says, laughing. “I remember when we first started the band, thinking, ‘Well, I won’t do this in my thirties cos I’ll just be too old.’ But as you play, you don’t think about that. You just sort of feel like yourself. You probably still feel like you’re twenty-five, until you see your reflection in a window or a mirror and you’re like, ‘Oh my God, what happened?’

“But no, I don’t think you could put an expiration date on something that still has life. I’ve always felt like there’s still life in this band, and there’s still songs in the band, and we’re still a fucking great live band, so I don’t know why we would stop.”