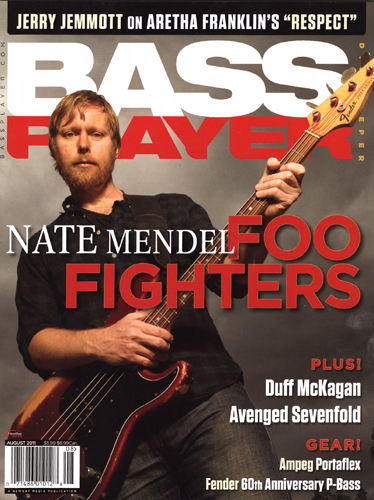

Mendelian Genesis

From his proto-emo explorations with Sunny Day Real Estate to his post-grunge grooves with Foo Fighters, Nate Mendel has learned loads about the dominant traits of great rock'n'roll bass playing. Pay attention, kids.

How did you first come to play bass?

How did you first come to play bass?

When I was 13 or 14 I had a friend who played guitar. He got it into his head that we should start a band. He suggested I play bass, and I said, "Okay, that sounds good!" That was at a time when I was first starting to go out and buy my own records and find my own taste. I was really into the Police especially Ghost In The Machine [A&M 1981].

How did you go about learning to play?

I knew a guy who played in a local band, and I took a couple lessons with him. But then I just started to experiment and figure things out on my own. All through high school I played in punk rock bands - mostly in a band called Diddly Squat. We did a couple of tours around the country in a van. It was part of the punk rock scene.

so it was do-it-yourself on a pretty small scale, but it was a lot of fun.

After that I moved to Seattle and joined Christ On A Crutch, another punk rock group that did a lot of touring. I was in the band for three or four years, and at the tail end I was becoming more enthusiastic about hardcore punk rock and wanting to play more intricate, interesting music. Thai's when I formed SuNNY Day Real Estate.

Which bands were making a mark on you?

My musical education was pretty limited - it was all hardcore punk rock, like Minor Threat, Black Flag and Bad Brains. Instead of studying the hass playing of someone like John Entwistle, which would have given me a foundation of how to play. I just wanted to play a lot of notes really fast. That was pretty much the only goal.

At that point, how did you understand your role as a bass player, and how did you go about playing that role in Sunny Day Real Estate?

When we got together, we were influnced by the music that was coming out of the Washington D.C. hardcore scene, especially bands like Rites Of Spring and Hayden. At the time, people were becoming more experimental within underground music, and not just thrashing out hardcore songs. That's what we were listening to. but we didn't sit down and strategize the kind of music we were going to play. We just got in a room and started making noise.

Some of the arrangements worked out well and may seem fairly sophisticated, but it was really just trial and error. It wasn't developed to a point where I would have understood my role in the band, per se. In retrospect, I can kick back and realize what an incredible opportunity it was as some body forming my own identity as a player. Because William Goldsmith was an incredible drummer — so passionate and so creative. We really played off each other. If he did something cool on the drums. I would try to come up with something that accentuated that. He'd hear me fiddling around with a part and he would do the same.

Writing was a labor-intensive process, but it worked out well. We wouldn't look at the song as a whole: we'd play one part of a song for an hour, and then somebody would take it off into amither direction. It was jam-oriented, as opposed to being a situation where a songwriter would come up with a chord structure and then bring it to the band. We had two guitar players who liked to play intertwined guitar parts, so it wasn't always clear what the root chord was. So I had a lot of freedom to come up with interesting bass lines.

How did you come to play with the Foo Fighters?

Dave Grohl recorded what turned out to be the first Foo Fighters record in early 1994. Sunny Day broke up later that year. Dave's tape was circulating around town, and I knew there might be an opportunity to try out for the band. So I started listening to it and playing along. From my perspective at the time, the music seemed rudimentary: I wasn't mature enough as a musician to know that a well-structured pop song should be simple.

At any rate, I was excited to maybe have an opportunity to make these songs as complicated as I could and put as much bass on there as possible, because that's all I heard. Basically, I came into the band wholly unprepared to play in it. You can kind of hear that on the first few records, where I'm trying to inject as much of my personality as I possibly could. Since then, I've realized that what I need to do is alter the way I play bass so it works in this band, so I can support Dave's songs as best as possible.

How has that approach changed the way you play?

I've always played with a pick, but up until the fifth Foo Fighters record, I never played downstrokes. I would alternate my picking. But with this kind of music, you need the consistency and percussive sound you get from playing with downstrokes. The other thing I've done is learn how to play tight and lock better with the drums. It comes down to subtlety and nuance; that was something I didn't grasp early on.

On the live album Skin and Bones, the band was going for a stripped-down acoustic sound. How did you change your playing to adapt?

I downsized to a combo amp, but it didn't change the sound much. I tried to play more fingerstyle. I wasn't comfortable with that at all at the beginning of that tour, but by the end, I had become fairly proficent at it.

You formed the Fire Theft in 2001. How was it different from what you were doing at the time with Foo Fighters?

I did that with William and Jeremy from Sunny Day Real Estate, and it was more fluid indie rock as opposed to the heavier. pop-oriented rock that Foo Fighters did. Those guys had started working on a record, and about halfway through the process they brought me in to it. By then, the basic structure was pretty well ironed out for most of the songs.

When we were doing Sunny Day Real Estate, it was a bunch of guys in a room hashing it out. But by this point Jeremy and I had become a more confident and mature musician, and he was very much the key songwriter. There was still the freedom to play whatever I felt like, and there was room to add different melodic elements in the band. Stylistically, it fell somewhere in between early Sunny Day Real Estate and Foo Fighters.

When the Foo Fighters played the VH1 Rock Honors show in 2O08, you took on two songs by the Who: 'Young Man Blues' and 'Bargain'. How did you approach recreating John Entwistle's parts?

That was a tough one, because you can't replicate what he did unless you spend hours and hours figuring out his gear, his technique, etc. Basically, I just listened to the records, and I tried to get as close as possible to playing what he played. My basic goal was to keep up and not make a total ass out of myself. As the Foo Fighters have had opportunities to play shows like the VH1 Rock Honors, we've had a few of these kinds of challenges thrown our way. I always feel like I'm playing catch-up, because I'm not a particularly special musician. But I've gotten pretty good at thinking on my feet.

To mark this year's Record Store Day on April 16, the Foo Fighters released Medium Rare, a limited-edition compilation of cover tunes you've done over the years. Are there any particular covers you feel most at home playing?

You basically form your identity as a musician when you're young, and for me that meant playing in Sunny Day Real Estate, a rock band that thought playing covers was a crazy idea. Then I got into the Foo Fighters, which plays a lot of covers. It was a good six or seven years into the band before I actually let on that I wasn't really fond of playing covers. But I think we've been pretty successful at doing them and making them interesting. For me, the best thing to do is to make it sound as little like the original as possible. I think our version of [Gerry Rafferty's] "Baker Street" turned out really well.

How did Wasting Light come together?

We took a nice break before doing this record. Dave went out and recorded and toured with Them Crooked Vultures. About a year and a half ago, he was on the road and starting to think about doing the next Foo Fighters record. He sent out this manifesto email that basically said, "This is how I see this next record happening." It had all these ideas - we'd get Butch Vig to produce it, it would be all analog, we'd do it in Dave's garage, and we'd make a documentary film about it. From that, we had a template for what we wanted to do. Dave had most of the song ideas sorted out by last summer.

Part of recording on tape is that we would need to know the songs before we went in. In the past, we'd often come up with parts in the studio, and the songs would evolve. For this one, we did enough pre-production and rehearsal that we could have done the record live. That's what Butch demanded, and that's the nature of recording to tape. We started recording in September in Dave's garage at his house and did a song a week for about 11 weeks.

You're most often seen playing various Fender Precision Basses. Which basses did you use to record the album?

I played all of Wasting Light on a Lakeland. We tried a few different basses, but we found the sound that worked best. We'd change the EQ to get the bass to fit in the mix. I love Lakeland basses, and I'm using them on tour for drop-D tunings right now. But I'm a bit more comfortable playing Fender basses, so I've gone back to playing those for most of the set.

Aside from your basses and Ashdown rig, are you running through any effects?

I use a overdrive pedal on one song, but I'm not using many pedals these days. Now that we have 3 guitar players, there's a lot of distortion going on. So I try to keep it clean and stay in line with the kick drum. That way, I know that even if we're playing a big echoy venue, at least the bass will come across with some bite and precision.

The album's second single, "Rope," has a riff that's particularly Intricate.

That song has been around for a while. Taylor [Hawkins] sometimes comes up with a rhythm on drums, and then bases a riff around that - that's how it happened with this song. I think he had that rhythm in his head and then figured out the chords and the structure. When we first heard it, it was just Dave playing it on the guitar; then we started jamming around with it. Taylor and Dave usually work on the drum parts together. Taylor comes up with ideas, and then Dave will say, "I want to hear it like this," or, "That's cool what you're doing there - try it this way," and we just build it up from there. Since Dave's a drummer, he has the advantage of rhythm being second nature to him. It allows him to do things that are a bit more complicated without having to think about it too much.

"I Should Have Known" is another interesting one, as it has both you and Foos guitarist Pat Smear playing bass.

Right. On the record, that's [Nirvana's] Krist Novoselic playing bass. Live, Pat plays his part on a double-neck Hagstrom, which is awesome. We're playing pretty much the same part; I'm just adding some passing notes and following the drums a little, while Pat plays it straight.

Motorhead is opening up for the Foo Fighters on a bunch of live dates. Dave seems to have a close relationship with Lemmy. Are the two of you friends, as well?

I like Lemmy, but he and I aren't exactly tight; if I were to design two people to be polar opposites, I'd probably come up with Lemmy and me. I really like his music, and I like that he walks it like he talks it. A lot of people who look like Lemmy turn out to be the sweetest people you ever meet - but Lemmy is actually kind of a badass, and I appreciate that about him. Plus, he's got his own style of playing. He does it his own way, and I think that's cool.

Are there any other bands you're playing with that are particularly cool?

Right now the opening act is Biffy Clyro, a Scottish band that's one of the most popular groups in Europe. They're absolutely great - a creative, heavy trio that puts a lot of thought into the music.

Words: Brian Fox

back to the features index

How did you first come to play bass?

How did you first come to play bass?