Holding court in the archival room of his 606

studio in Northridge, in the San Fernando Valley,

Dave Grohl talks about the Fooeys’ ninth album,

Concrete And Gold, their odd choice for a producer

(Sia and P!nk producer Greg Kurstin), the secret guest

appearances and the record’s unique sound (which can be

described quite aptly as “Slayer meets The Beach Boys”).

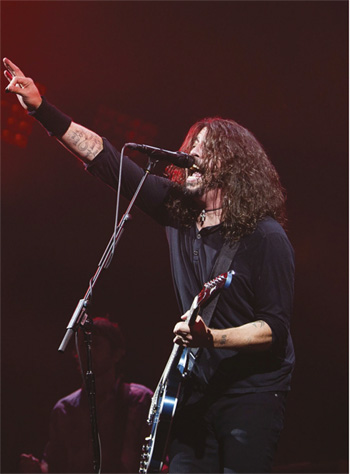

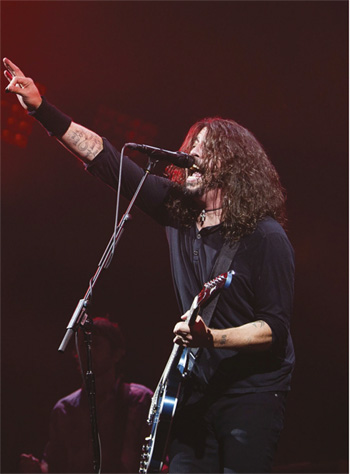

If the Foo Fighters want to keep listeners on the edges of

their seats nine albums in, after all, they’re going to need

to take some solid leaps into the unknown and unusual.

Grohl also opens up about age, needing glasses, his

throne for rent and the surprisingly normal experiences

of having his mum follow him around on tour.

So you need glasses these days too?

So you need glasses these days too?

Oh God, it’s the worst.

We’re getting old, man. It starts with losing sight.

I know. I actually wanted glasses when I was young, because my sister had them. You did?

I did. She had braces and glasses, and I was so jealous because she had all the accoutrements [laughs]. And then when I turned 40, eight years ago, my optometrist said, “Well, you need glasses.” I was like, “Yay! I’m getting glasses!” But now I’m like, “Fuck glasses.” They drive me crazy. If I forget them, I can’t read menus. I have to ask people to read me the menu. It’s embarrassing. It’s terrible.

I thought you were planning to take a full year off, but obviously you can’t really do that, can you?

Yeah. I tried. I really did [laughs].

What happened? Weren’t your kids happy that you were around for a change?

It’s funny, because at one point my kids said, “Dad, you’re going to have to go on tour again, right?” And I said, “Yeah, but I’m going to take some time off – maybe a year.” And they were like, “No, no, no, no, Dad, you shouldn’t take that much time off. Maybe six months, and then you can go back out on the road.” I was like, “Oh my God.” But I honestly thought that it would be good for all of us to get away for a while, because the last tour was really long.

I also broke my leg, and physically, that was really challenging. We did 50 or 60 shows after I’d broken my leg, and I had a blast. It was great. The shows where I was sitting in that ridiculous throne thing – that was really fun, I fucking loved it. And they were some of the best shows we’ve ever played. But those were the best three hours of the day. It was the other 21 hours that were really a challenge, y’know, because I was on crutches or in a wheelchair. So not only was it physically challenging, but after a while it became emotionally difficult as well. I thought that the best thing for the band to do would be just to stop and get away from it for a while. We’ve always felt that if we get to the point where [the integrity of the band] is just about to snap or it’s just about to break, then we back off and we say, “We should stop.” But we actually enjoy doing it, so it’s hard to spend too much time away – I feel like I need to do it. Like, I need to play music with these guys. It’s such a big part of my life that when I’m away from it for six months, eight months, whatever it is, I actually feel empty in a way. And so I was approaching other ideas, like film projects – directing movies and stuff like that – just to do something other than the band. At one point, I actually felt strange because I was approaching a project, but my passion wasn’t the same as it is with the band. And I realised that I’d never felt like that when I’m with them – I’ve never had to manufacture some inspiration to be in the Foo Fighters. It’s always been real. And here I was trying to create some inspiration or energy to do something else. And I realised, like, “Oh, that’s what it’s like when your heart isn’t 100 percent in it. And so it was around then that I started to realise that the best thing for me wasn’t a break – it was to make music with the band. At one point, I thought that music was the thing that was making me exhausted and fucking up my head. But after six months, I was like, “No, wait. Music is what keeps me from going crazy!”

So breaking your leg and sitting on that throne for 60 gigs…

Yeah.

Have you never thought, “Am I getting too old for this?”

Oh, I’ve felt like that for the last 15 years! [Laughs]. I remember when we first started the band – I think I was 25 or 26 – I thought: “Well, I won’t do this in my 30s because then I’ll just be too old,” y’know? But when you’re playing, you don’t really think about that. Just as I’m sure you don’t walk through life thinking that you’re 48 years old all the time, y’know? You just sort of feel like yourself. You probably still feel like you’re 25 years old until you see your reflection in a window or a mirror and you’re like, “Oh my God, what happened!?” So no, I don’t think you could put an expiration date on something that still has life. And I’ve always felt like there’s still life in this band – we’ve still got songs to play and we’re still a fucking great live band – so I don’t know why we would stop, y’know?

Is that where the passion comes from? Is that what keeps the fire burning after nine albums?

It’s just the sheer love and enjoyment I get from creating the music with my friends and then going out and seeing the enthusiasm of these huge audiences. If we went out and the audiences didn’t respond to what we were doing, and we didn’t enjoy making the music, then we wouldn’t do it. But it starts with the band, and an assurance that we actually enjoy doing it. We feel creatively fulfilled when we make a record, but when we go to play live and there’s 100,000 people singing along to a song, it’s like... That, to me, is what life is all about – connecting all of these people with a lyric or a riff. That’s what gives me hope. When I come home from a tour where we’ve just sung along to all of our songs with thousands of people every night, it’s like the mundanity of normal life is all worth it. I feel okay with driving a minivan to a bus stop, packing lunches, going to the grocery store and picking up dog shit in my yard. It’s a nice balance of two things, y’know?

Greg Kurstin sounds like an odd choice for a producer, but it obviously worked very well for this record.

Yeah. I met him maybe three or four years ago – I was driving in my car one day, and I heard a song by his band, The Bird And The Bee, who I’d never heard before. It was called “Again And Again”, and it’s almost like an electronic version of “Girl From Ipanema”: really jazzy with a female vocalist – her name is Inara George – but the melodies and the harmonies were so deep. I mean, I was like jazz, but it also sounded like a Beach Boys thing. It had this sort of ‘70s rock feel to it, but it was modern, electronic music. And musically, it was just so lush and beautiful. So I bought the record, and I became obsessed with the album because all of the compositions. There’s a song called “I’m A Broken Heart”, which could have been on Pet Sounds. It just sounds so fucking genius, it’s amazing.

So I was in Hawaii – this was four years ago, maybe two or three months after I bought the record. I was in a restaurant where I saw Greg, and I was like: “Oh my God, that’s the guy from The Bird And The Bee, holy shit.” I walked up to him in the restaurant and I said, “I’m sorry, I don’t want to interrupt, but I’m such a huge fan of your record and you’re a fucking genius.” I was like, “What are you doing here?” He was like, “Oh, I have a house here,” and I said, “What’s going on with The Bird And The Bee?” He said, “We’re going to make another record, but I have to finish producing for Sia and Adele, and Beyonce and P!nk.” And I was like, “Oh my God.” We became friends, and every time I’d go to Hawaii, I’d see him there and we’d talk about music. We’d talk about Bad Brains and The Beatles, The Beach Boys and Dead Kennedys, or Kraftwerk, or whatever – he’s a music lover like me, and he has this encyclopedic knowledge of production and arrangement and composition. He’s a studied jazz musician – that’s his first love – so he doesn’t just think of music as a series barre chords; he thinks of music in these really outside and deep terms. Like, from a jazz perspective.

Is that why there’s a piano on one song?

Yeah, that was Greg.

And a jazz moment in another one?

And a jazz moment in another one?

That’s Greg as well. That came about one day where he was just in the room, playing by himself with the piano, and I said, “Record it!” And they put it on. But the great thing about Greg is that he can either go way outside into the jazz world, or he could do a song like “Hello” by Adele – that’s him playing all the instruments on that song – or a Sia song. He has a really good idea of pop composition, but musically, he’s just so much bigger than that.

Was it him that sparked the idea of an album that’s almost like Slayer meets The Beach Boys?

Well, that’s something I’ve always wanted to do. I’ve always wanted to make a record where, musically or instrumentally or dynamically, it’s really diverse. Every record has its moments of that, whether it’s the first and second records with stuff like “February Stars” and “See You”, or Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace where there’s a lot of that stuff. And on In Your Honor, there’s the acoustic side and the rock side. So it’s something that I’ve always wanted to do, but when I met Greg, I realised he was the person that was going to do it bigger and better than we’ve ever done it before. Anywhere you want to go, he’ll take you farther than you thought you could. If you say, “I want this to be really thrashy and noisy,” you’ll end up with a song like “La Dee Da”, which is just fucking [imitates feedback] – it’s really fucking noisy. If you say, “I want this to sound really huge, like a choir,” then you get a song like “Concrete And Gold”, where it goes from being this really spare, dark Black Sabbath-esque riff to exploding into this mushroom cloud of fucking choirs. He just knows how to take you there. The Bird And The Bee played a role in it as well – I always thought, “What if the Foo Fighters made a record with the vocal harmonies that Bird And The Bee have sometimes – these sweet, beautiful melodies over those really fucking heavy riffs.” I think they really complement each other.

Well, you love The Pixies, don’t you?

Y’know, I grew up listening to The Beatles when I was young. That’s how I learned to play the guitar – I had my first guitar, a Beatles songbook and some Beatles records, and I would just play along with them. But the songs that I really loved the most were the ones that were kind of dark and sinister, like “She’s So Heavy” – the riff on that song is almost like the first dark metal riff. It’s like, you close your eyes and it’s got this really sinister vibe to it. But the vocals on it are so beautiful and the harmonies they stack on it are so fucking pretty, and I knew that when I was ten, so that’s sort of written into my DNA zipper, musically. And this time, making Concrete And Gold, we actually got to the place where I feel satisfied that we did the one thing I’ve always wanted to do.

Why did you make such a secret out of the recording sessions, and the guests involved?

We told everybody about most of them. We told everybody about the singer of Boyz II Men, Alison from The Kills and Inara George from Bird And The Bee. But there was one person in the studio at the same time that we were there, who I didn’t realise was a fan and who I’d met a few times but never really hung out with. We became friends and I played them a bunch of our new record, and after about a week, they said, “Hey, can I sing on your record?” It’s someone that you would never imagine being on a Foo Fighters record, but I said, “Absolutely.” So we found a part and they sang on it, but then we sort of decided together, “Let’s keep it a secret. Let’s not tell anybody.”

About a month [before the album was released], someone asked me about the guests, so I listed them but I said, “Well, there’s another person, but I promised them I wouldn’t tell you who they are.” And so then it became this guessing game: “Is it Taylor Swift? Is it Adele?” It’s someone that is incredibly talented, musically, and has been around for a really long time. Their track is one of the heaviest songs on the album, and heavy songs is not something that this person does.

Is “Dirty Water” about the water pollution in Flint, Michigan?

[Laughs] How did you know!?

I did my research.

[Laughs] No, “Dirty Water” is about feeling polluted by that black cloud of oppression you feel sometimes, whether it affects the way your heart works or it affects the way you think. It’s that feeling where you’re bleeding dirty water and breathing dirty sky – you just kind of feel polluted by that sort of dark energy of the collective psyche of the world, y’know?

That title, Concrete And Gold, really sums up the sound of the album, doesn’t it?

Yeah, it’s funny.

The heaviness and the beauty of it.

I didn’t make that connection at first. When I went to sing these songs and when I went to write those lyrics, I went into a house in the woods for a week, just by myself, and I would like drink a bottle of wine and just... [screams]. Just, like, scream anything into a microphone. And these were the things that were coming out. I wasn’t writing them on paper, I was just singing along. It was kind of like this unfiltered stream of consciousness that was coming out. That lyric just came out of nowhere, and I eventually realised that not only does it serve as this hopeful finale to the album, but it also represents the juxtaposition or the duality of the sound of this record. It represented that there’s that raw foundation of fucking noisy rock riffs, but then those beautiful, shiny melodies and harmonies that go on top of them.

So I’ve read From The Cradle To The Stage.

Oh, good.

I didn’t know that your mum follows you on tour sometimes.

Oh yeah, she’s been everywhere. Most people, when they retire, they go on a cruise ship and they travel the world, and they do all of those things. And when my mother retired from being a school teacher 20 years ago, I thought, “Well, my life is like a cruise ship, y’know? Just come onboard!” And she’s travelled with us to Australia and Japan and Europe and Canada – she’s been everywhere with us. I was a little nervous at first, because I didn’t want her to just get lost in this crazy production. But after a while, I would just give her a laminate and say, “I’ll see you after the show.” She knows everybody and makes friends with everybody, has a drink and watches the show.

And you’re not feeling intimidated? I would if my mother was watching me at all time…

Well, no. Honestly, my mother has been so supportive of me for my whole life. She was also a musician when she was young – she sang in an acapella group – so she’s always been very supportive and proud of what I’ve done as a musician. So that’s nice.

She made this comment that she actually feared Madonna would snatch you up.

I don’t know why she said that. That was not… [Laughs] That was not an option at any point.

So you need glasses these days too?

So you need glasses these days too?Oh God, it’s the worst.

We’re getting old, man. It starts with losing sight.

I know. I actually wanted glasses when I was young, because my sister had them. You did?

I did. She had braces and glasses, and I was so jealous because she had all the accoutrements [laughs]. And then when I turned 40, eight years ago, my optometrist said, “Well, you need glasses.” I was like, “Yay! I’m getting glasses!” But now I’m like, “Fuck glasses.” They drive me crazy. If I forget them, I can’t read menus. I have to ask people to read me the menu. It’s embarrassing. It’s terrible.

I thought you were planning to take a full year off, but obviously you can’t really do that, can you?

Yeah. I tried. I really did [laughs].

What happened? Weren’t your kids happy that you were around for a change?

It’s funny, because at one point my kids said, “Dad, you’re going to have to go on tour again, right?” And I said, “Yeah, but I’m going to take some time off – maybe a year.” And they were like, “No, no, no, no, Dad, you shouldn’t take that much time off. Maybe six months, and then you can go back out on the road.” I was like, “Oh my God.” But I honestly thought that it would be good for all of us to get away for a while, because the last tour was really long.

I also broke my leg, and physically, that was really challenging. We did 50 or 60 shows after I’d broken my leg, and I had a blast. It was great. The shows where I was sitting in that ridiculous throne thing – that was really fun, I fucking loved it. And they were some of the best shows we’ve ever played. But those were the best three hours of the day. It was the other 21 hours that were really a challenge, y’know, because I was on crutches or in a wheelchair. So not only was it physically challenging, but after a while it became emotionally difficult as well. I thought that the best thing for the band to do would be just to stop and get away from it for a while. We’ve always felt that if we get to the point where [the integrity of the band] is just about to snap or it’s just about to break, then we back off and we say, “We should stop.” But we actually enjoy doing it, so it’s hard to spend too much time away – I feel like I need to do it. Like, I need to play music with these guys. It’s such a big part of my life that when I’m away from it for six months, eight months, whatever it is, I actually feel empty in a way. And so I was approaching other ideas, like film projects – directing movies and stuff like that – just to do something other than the band. At one point, I actually felt strange because I was approaching a project, but my passion wasn’t the same as it is with the band. And I realised that I’d never felt like that when I’m with them – I’ve never had to manufacture some inspiration to be in the Foo Fighters. It’s always been real. And here I was trying to create some inspiration or energy to do something else. And I realised, like, “Oh, that’s what it’s like when your heart isn’t 100 percent in it. And so it was around then that I started to realise that the best thing for me wasn’t a break – it was to make music with the band. At one point, I thought that music was the thing that was making me exhausted and fucking up my head. But after six months, I was like, “No, wait. Music is what keeps me from going crazy!”

So breaking your leg and sitting on that throne for 60 gigs…

Yeah.

Have you never thought, “Am I getting too old for this?”

Oh, I’ve felt like that for the last 15 years! [Laughs]. I remember when we first started the band – I think I was 25 or 26 – I thought: “Well, I won’t do this in my 30s because then I’ll just be too old,” y’know? But when you’re playing, you don’t really think about that. Just as I’m sure you don’t walk through life thinking that you’re 48 years old all the time, y’know? You just sort of feel like yourself. You probably still feel like you’re 25 years old until you see your reflection in a window or a mirror and you’re like, “Oh my God, what happened!?” So no, I don’t think you could put an expiration date on something that still has life. And I’ve always felt like there’s still life in this band – we’ve still got songs to play and we’re still a fucking great live band – so I don’t know why we would stop, y’know?

Is that where the passion comes from? Is that what keeps the fire burning after nine albums?

It’s just the sheer love and enjoyment I get from creating the music with my friends and then going out and seeing the enthusiasm of these huge audiences. If we went out and the audiences didn’t respond to what we were doing, and we didn’t enjoy making the music, then we wouldn’t do it. But it starts with the band, and an assurance that we actually enjoy doing it. We feel creatively fulfilled when we make a record, but when we go to play live and there’s 100,000 people singing along to a song, it’s like... That, to me, is what life is all about – connecting all of these people with a lyric or a riff. That’s what gives me hope. When I come home from a tour where we’ve just sung along to all of our songs with thousands of people every night, it’s like the mundanity of normal life is all worth it. I feel okay with driving a minivan to a bus stop, packing lunches, going to the grocery store and picking up dog shit in my yard. It’s a nice balance of two things, y’know?

Greg Kurstin sounds like an odd choice for a producer, but it obviously worked very well for this record.

Yeah. I met him maybe three or four years ago – I was driving in my car one day, and I heard a song by his band, The Bird And The Bee, who I’d never heard before. It was called “Again And Again”, and it’s almost like an electronic version of “Girl From Ipanema”: really jazzy with a female vocalist – her name is Inara George – but the melodies and the harmonies were so deep. I mean, I was like jazz, but it also sounded like a Beach Boys thing. It had this sort of ‘70s rock feel to it, but it was modern, electronic music. And musically, it was just so lush and beautiful. So I bought the record, and I became obsessed with the album because all of the compositions. There’s a song called “I’m A Broken Heart”, which could have been on Pet Sounds. It just sounds so fucking genius, it’s amazing.

So I was in Hawaii – this was four years ago, maybe two or three months after I bought the record. I was in a restaurant where I saw Greg, and I was like: “Oh my God, that’s the guy from The Bird And The Bee, holy shit.” I walked up to him in the restaurant and I said, “I’m sorry, I don’t want to interrupt, but I’m such a huge fan of your record and you’re a fucking genius.” I was like, “What are you doing here?” He was like, “Oh, I have a house here,” and I said, “What’s going on with The Bird And The Bee?” He said, “We’re going to make another record, but I have to finish producing for Sia and Adele, and Beyonce and P!nk.” And I was like, “Oh my God.” We became friends, and every time I’d go to Hawaii, I’d see him there and we’d talk about music. We’d talk about Bad Brains and The Beatles, The Beach Boys and Dead Kennedys, or Kraftwerk, or whatever – he’s a music lover like me, and he has this encyclopedic knowledge of production and arrangement and composition. He’s a studied jazz musician – that’s his first love – so he doesn’t just think of music as a series barre chords; he thinks of music in these really outside and deep terms. Like, from a jazz perspective.

Is that why there’s a piano on one song?

Yeah, that was Greg.

And a jazz moment in another one?

And a jazz moment in another one?That’s Greg as well. That came about one day where he was just in the room, playing by himself with the piano, and I said, “Record it!” And they put it on. But the great thing about Greg is that he can either go way outside into the jazz world, or he could do a song like “Hello” by Adele – that’s him playing all the instruments on that song – or a Sia song. He has a really good idea of pop composition, but musically, he’s just so much bigger than that.

Was it him that sparked the idea of an album that’s almost like Slayer meets The Beach Boys?

Well, that’s something I’ve always wanted to do. I’ve always wanted to make a record where, musically or instrumentally or dynamically, it’s really diverse. Every record has its moments of that, whether it’s the first and second records with stuff like “February Stars” and “See You”, or Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace where there’s a lot of that stuff. And on In Your Honor, there’s the acoustic side and the rock side. So it’s something that I’ve always wanted to do, but when I met Greg, I realised he was the person that was going to do it bigger and better than we’ve ever done it before. Anywhere you want to go, he’ll take you farther than you thought you could. If you say, “I want this to be really thrashy and noisy,” you’ll end up with a song like “La Dee Da”, which is just fucking [imitates feedback] – it’s really fucking noisy. If you say, “I want this to sound really huge, like a choir,” then you get a song like “Concrete And Gold”, where it goes from being this really spare, dark Black Sabbath-esque riff to exploding into this mushroom cloud of fucking choirs. He just knows how to take you there. The Bird And The Bee played a role in it as well – I always thought, “What if the Foo Fighters made a record with the vocal harmonies that Bird And The Bee have sometimes – these sweet, beautiful melodies over those really fucking heavy riffs.” I think they really complement each other.

Well, you love The Pixies, don’t you?

Y’know, I grew up listening to The Beatles when I was young. That’s how I learned to play the guitar – I had my first guitar, a Beatles songbook and some Beatles records, and I would just play along with them. But the songs that I really loved the most were the ones that were kind of dark and sinister, like “She’s So Heavy” – the riff on that song is almost like the first dark metal riff. It’s like, you close your eyes and it’s got this really sinister vibe to it. But the vocals on it are so beautiful and the harmonies they stack on it are so fucking pretty, and I knew that when I was ten, so that’s sort of written into my DNA zipper, musically. And this time, making Concrete And Gold, we actually got to the place where I feel satisfied that we did the one thing I’ve always wanted to do.

Why did you make such a secret out of the recording sessions, and the guests involved?

We told everybody about most of them. We told everybody about the singer of Boyz II Men, Alison from The Kills and Inara George from Bird And The Bee. But there was one person in the studio at the same time that we were there, who I didn’t realise was a fan and who I’d met a few times but never really hung out with. We became friends and I played them a bunch of our new record, and after about a week, they said, “Hey, can I sing on your record?” It’s someone that you would never imagine being on a Foo Fighters record, but I said, “Absolutely.” So we found a part and they sang on it, but then we sort of decided together, “Let’s keep it a secret. Let’s not tell anybody.”

About a month [before the album was released], someone asked me about the guests, so I listed them but I said, “Well, there’s another person, but I promised them I wouldn’t tell you who they are.” And so then it became this guessing game: “Is it Taylor Swift? Is it Adele?” It’s someone that is incredibly talented, musically, and has been around for a really long time. Their track is one of the heaviest songs on the album, and heavy songs is not something that this person does.

Is “Dirty Water” about the water pollution in Flint, Michigan?

[Laughs] How did you know!?

I did my research.

[Laughs] No, “Dirty Water” is about feeling polluted by that black cloud of oppression you feel sometimes, whether it affects the way your heart works or it affects the way you think. It’s that feeling where you’re bleeding dirty water and breathing dirty sky – you just kind of feel polluted by that sort of dark energy of the collective psyche of the world, y’know?

That title, Concrete And Gold, really sums up the sound of the album, doesn’t it?

Yeah, it’s funny.

The heaviness and the beauty of it.

I didn’t make that connection at first. When I went to sing these songs and when I went to write those lyrics, I went into a house in the woods for a week, just by myself, and I would like drink a bottle of wine and just... [screams]. Just, like, scream anything into a microphone. And these were the things that were coming out. I wasn’t writing them on paper, I was just singing along. It was kind of like this unfiltered stream of consciousness that was coming out. That lyric just came out of nowhere, and I eventually realised that not only does it serve as this hopeful finale to the album, but it also represents the juxtaposition or the duality of the sound of this record. It represented that there’s that raw foundation of fucking noisy rock riffs, but then those beautiful, shiny melodies and harmonies that go on top of them.

So I’ve read From The Cradle To The Stage.

Oh, good.

I didn’t know that your mum follows you on tour sometimes.

Oh yeah, she’s been everywhere. Most people, when they retire, they go on a cruise ship and they travel the world, and they do all of those things. And when my mother retired from being a school teacher 20 years ago, I thought, “Well, my life is like a cruise ship, y’know? Just come onboard!” And she’s travelled with us to Australia and Japan and Europe and Canada – she’s been everywhere with us. I was a little nervous at first, because I didn’t want her to just get lost in this crazy production. But after a while, I would just give her a laminate and say, “I’ll see you after the show.” She knows everybody and makes friends with everybody, has a drink and watches the show.

And you’re not feeling intimidated? I would if my mother was watching me at all time…

Well, no. Honestly, my mother has been so supportive of me for my whole life. She was also a musician when she was young – she sang in an acapella group – so she’s always been very supportive and proud of what I’ve done as a musician. So that’s nice.

She made this comment that she actually feared Madonna would snatch you up.

I don’t know why she said that. That was not… [Laughs] That was not an option at any point.